Chapter 5

Eh!

Oh!

Away

from the ocean the sailor is never in his element. He falls a prey to the

sharp practices of swindlers and city sharks; he becomes the laughing stock

of the townsmen. Likewise is the peasant when he is off his land. Clever

people exploit his simplicity, his ingenuousness and his capacity to work.

He may be made the butt of many a jest, or the victim of a practical joke,

and he bears his cross on his ample shoulders patiently.

Owing to the

rigour of the climate in Kashmir, the peasant has to pass through a period

of unemployment for nearly five months in a year. The well-to-do farmers

can afford to enjoy this enforced rest, consuming cooked rice, lentils,

turnips and pickled knol-kohl to their hearts' content. Those who are not

so well-off supplement their slender incomes by working on cottage looms

arid turning out woollen blankets. Others, standing at the lowest rung

of the ladder, hire themselves out as domestic servants in the larger towns,

or the metropolis of Srinagar. Aziz Buth belonged to this last class.

Many, many

years ago when the corn was abundant to the extent of superfluity, Aziz

Buth could not stretch his harvest so far as to cover the needs of the

family all the year round. He was the father of two children, and in spite

of the labours of the whole family—even the elder child would sometimes

contribute his mite—he ran into debt. He was, therefore, compelled to drift

towards the city in search of temporary employment as a domestic servant.

Untutored in

the ways of the world as he was, he did not think it would be easy for

him to find some employment in the city. He spent the first night in a

mosque wrapped in a blanket, for he knew of no secular habitation where

he could obtain shelter. He feasted on a couple of dry loaves and sincere

prayers rose from his heart. The next morning had a pleasant surprise for

him, for he met an acquaintance—a rare experience for him. The man belonged

to a village in the neighbourhood of his own, and they knew each other

moderately well. Aziz Buth considered his night well-spent when his acquaintance

promised to get him the sort of employment he was after.

The acquaintance

was as good as his word. Aziz Buth was taken to the house of a man who

appeared to be very prosperous. There were already a couple of servants

in the house and Aziz Buth made the third. Khwaja Saheb, that is how the

head of the house was designated, called him to his presence and said,

"Many people proudly seek my service for the consideration of free board

and lodging. Will that satisfy you?"

Aziz Buth was

so overawed by the manner of the Khwaja in his costly shawl and turban

that he found words missing from his tongue. With difficulty he seemed

to stammer out: "Noble sir, I am a poor man having left little ones in

the village."

Khwaja Saheb

was thereupon pleased to fix half-anass load of paddy as his monthly wages

besides the privilege of free board and lodging. "But, mind you, if ever

one of my servants is not able to complete a task given to him, he is subjected

to a fine," said he, half in jest and half in seriousness. Aziz Buth's

companion only laughed "ha! ha" by way of taking the sting out of these

words and he himself grinned bashfully.

The winter

was on and Aziz Buth gave his best to the employer Late at night before

he went to his bed Aziza had the privilege of being admitted to the bed

chamber of his employer. He was asked to massage the legs of the Khwaja

with his strong muscular hands, for he found sleep evading him until he

was subjected to this process. Early in the morning, sometimes even before

the cock crew, the Khwaja would shout "Aziza" and the latter was expected

to be ready with the hubble-bubble, refilled with fresh water from the

river, with tobacco and live coal to enable his employer to fumigate his

interior to his fill. He was the favourite of the harem in so far as he

would be entrusted with all tasks requiring personal attention. His colleagues—the

fellow servants in the house—encouraged him in this belief, for otherwise

such tasks would fall to their own lot. This encouragement lightened their

own tasks, for Aziza could easily be got into the right frame of mind so

as to volunteer to undertake what all shirked.

The winter

turned out to be extra severe. Householders, who could afford to do so,

avoided leaving their homes as far as possible. But domestics like Aziza

had no choice in matters like these. In fact the comforts available in

the home of the Khwaja Saheb depended a great deal upon the exertions of

men like Aziza, and the latter was modestly proud of the part he played

in this respect.

At the end

of a period of about four months Aziza thought of going home. He had not

seen his family all the while and soon his farm would claim his attention.

He made a request to the great Khwaja, the first of its kind. The latter

did not seem to relish it, and with a face beaming with a mischievous smile

he said, "Aziza ! I shall certainly pay all your dues. But before I do

so, go to the market and get me two things, wy (eh!) and wai (oh!). Your

wages will be paid to you only when you get the things." "Eh and Oh!" ejaculated

Aziza in utter amazement, for he had never heard of such things. However,

he had not the face to articulate his suspicions lest it be only his ignorance.

So he set out.

Long he roamed

and far, but never did any shopkeeper seem to deal in these substances.

Some laughed outright, others pricked their ears while some came to regard

him light in the head. "Should I fail in this last task?" cried he. "All

these months I worked to the utter satisfaction of everybody' arid now

this last straw seems to be too much for me And the big man will probably

eat up my wages if I fail to satisfy him.... "

He was walking

abstractedly, with these thoughts pressing upon his mind. He went from

shop to shop. At the seventh or the seventeenth shop he met with a different

response to his inquiry. 'And what do you require them for, my good man?"

asked the shopkeeper, an oldish man with a rich stubble on his face. Aziza

told his tale.

"And if you

fail to place them before him you won't get our pay, your hard-earned dues,

is that it?"

"Exactly; that

is what the man threatens me with."

The old man

soon found out that the Khwaja was trading upon the simplicity of the peasant.

He was himself something of a sport and he thought of playing the game

for the fun of it.

"I can give

it to you provided you hand it over directly to the Khwaja himself without

showing it to any one else. Do you agree?"

Aziza agreed.

"It is meant

for Khwaja Saheb. Do not spoil it by examining it yourself or fingering

it," the shopkeeper insisted.

"Not at all,

sir; and God bless you for coming to my rescue. I went over from shop to

shop but nobody seems to stock it," said Aziza with a feeling of relief.

"Such precious

things are not found with every grocer. Even I keep it in a godown. You

will wait here for me."

He returned

after half-an-hour and gave Aziza a package covered in an old newspaper

bound with a dried weed. He got eight annas for his pains and Aziza was

glad that he could now keep his head high in the presence of all the other

servants in that he had not failed in his errand.

The Khwaja

expected Aziza to return and report failure and crave his mercy, for when

God created this universe out of His bounty, he forgot to give a corporeal

frame to "eh!" and "oh !". According to the verbal agreement which, of

course, was morally binding upon Aziza the latter's failure to work up

to the satisfaction of the master would result in forfeiting his wages.

The Khwaja was thus looking forward to a lot of fun: his verdict that Aziza

was no longer entitled to his wages would bring Aziza prostrate before

him, but that he would stick to his word till ultimately he would condescend

to release part of the amount....

The Khwaja

was in a very rosy mood when Aziza appeared before him. The tube of the hubble-bubble passed from one mouth to another. Seeing Aziza he simulated

an angry mood. "Where, in the name of God Almighty, have you been all this

while," he shouted. "I sent you on a little errand and you seem to have

been lazing at your grandmother's. How fat you have grown eating my cooked

rice here!"

"Respected

sir, I have been roaming from street to street in search of it and my legs

are aching with the fatigue," replied Aziza.

"If your legs

are so delicate, why did you take the trouble of coming over here for employment?

Did you not get the thing?"

"Respected

sir, I have got it," submitted Aziza.

The Khwaja

relaxed as he now expected to fill the little assembly with theatrical

laughter by declaring what Aziza had got as spurious. "What have you got?

Let me see it," he said in an over-weening tone.

Aziza submitted

the little package. The whole gathering was intrigued. The outer chord

of dry weed was unfastened and the wrapping removed. Two small earthenware

receptacles, no bigger than a medium sized ink pot, were discovered. Each

had a wide mouth closed over with a piece of paper pasted with gum. Their

inquisitiveness was piqued.

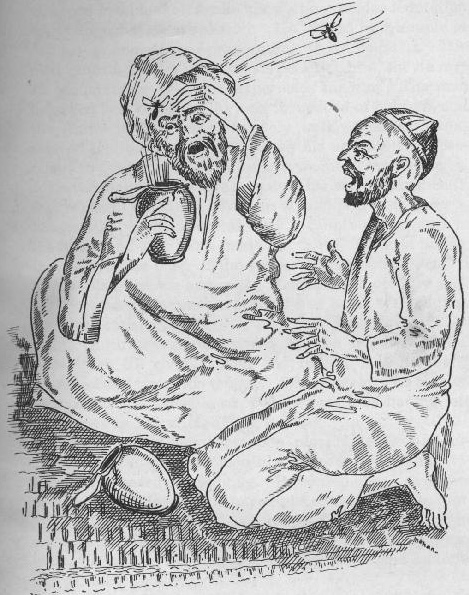

The paper covering

of one of the vessels was broken through and the Khwaja peered into it.

It appeared to be empty. While he was about to throw it away out came a

bee which buzzed along the hand of the Khwaja who could not help crying

"oh!" So far so good.

The paper lid

of the other vessel was broken through. But before the Khwaja could say

anything, from its interior darted a wasp who perched directly on his brow

and involuntarily a painful "oh!" escaped from his lips.

The assembly

realized that Aziza had after all not failed to get the rare commodity!

|