Chapter

13

The

Upstart

The

house of the nobleman wore a festive appearance. In celebration of some

important function an invitation to dinner was thrown to many relations

and friends. The nobleman was seated in his reception hall, a large room

on the ground floor. The walls were painted with arabesques in different colours, green, white, orange and blue-black. The ceiling was in the famous

khatumband style.

There were several large windows, consisting of beautiful lattice work

provided with shutters of wood painted in a fine slate colour.

The windows

were mounted with ventilators fitted with glass panes to let the light

in when the lattices and shutters were fastened owing to excessive cold

as on the present occasion. The room was covered with large carpets in

loud colours.

It was pretty

cold outside and the guests arrived severally in their warm clothings, pherans with

fine shawls or finer pashmina woollen blankets wrapped over. They

took their seats on the carpet squatting in accordance with the importance

of their social position or their proximity to the host in relationship.

They shared the class tie, for most of them were landholders or state employees,

and of course, they drew strength from one another. The face of the host

reflected satisfaction as guest after guest arrived to take his seat. Ladies

were being seated in a separate room in keeping with the age-old tradition.

Conversation was warm and cheering.

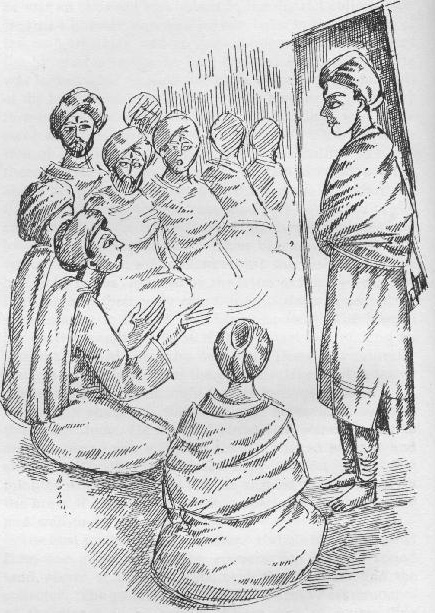

There was a

feeling of slight embarrassment on the face of the host on the arrival

of one guest. He was neither a member of the elite social circle to which

the host belonged nor a relation. He owed the invitation to his office,

for he was an assistant accountant in the district collectorate. He had

a humble start as a private tutor to the children of the naib-tehsildar, and

an unpaid apprentice in his court till by gradual steps he had attained

this position. He was looked upon as some sort of an upstart by the families

of the landholders, but was tolerated because of his utility in remissions

of arrears of rent. This official was handsome and intelligent and was

convinced of the contribution of a befitting apparel to one's personality.

He was therefore, always well-dressed, in fact dressed a little above his

position according to the sartorial standards of the time. Those others

whose shoulders he aspired to rub socially felt it an encroachment on their

privileges and looked askance upon him. When he came dressed in a white pheran and

a fine blanket into the gathering of the hierarchy it was regarded by the

latter as if he were carrying war into their very camp, for his dress appeared

no whit inferior to that of the "blue-blooded." The host in his exalted

position felt as if the upstart was making an attempt to beard him in his

own den. There was naturally a scowl on his face when the official arrived

but it lasted a brief while as he camouflaged his feelings at once.

It was a challenge

which he was determined to meet there and then. He excused himself on some

pretext to an adjoining room and sent for his trusted servant and steward.

The two were closeted together for quite a few minutes while the guests

outside regaled themselves with the brew of Ladakhi brick tea, a speciality

of respectable and well-to-do families.

The host joined

them soon after. Hubble bubbles moved from one guest to another, conversation

centred round land, clever or lazy peasants, rent, the tehsildar and

the collector. The gunfire from the Hari Parbat Fort announced the dinner

to be served. There was, of course, fine basmati rice served with

a number of courses in meat: roganjosh, kabab or mincemeat, meat-curry

cooked with turnips. The host went round from guest to guest inquiring

after their pleasure and keeping up the conversation. He showered special

attention on the assistant accountant at whose back the steward had taken

his seat.

The conversation

touched the early school days of the guests who, one by one, vividly recalled

their maktabs in the house of the teacher and the instruments of

punishment—the mulberry switch, and the rope hanging from the ceiling to

suspend the recalcitrants in the inverted pose. One of them told the audience

how he had once been made to lie naked on the bed covered with the prickly

weed and was thrashed liberally with the same weed for the offense of taking

a bath in the river. Another explained how as the monitor he was asked

by the teacher to stamp the legs of the boys with his own stamp to prevent

their taking a bath and how he (the monitor) was himself discovered by

the teacher swimming in the river. They, however, expressed gratitude to

the ancient school where they got a grounding in Persian and quoted liberally

from Gulistan, Bostan and other classics. They were meanwhile kept

busy with pilau with which pickles of cabbage and radish were served.

The last course consisted of kabargah which when consumed prepared

the guests for washing their hands. Two servants went round, one with a

jug of warm water and another with a basin to help the guests to clean

their hands.

Those who cleaned

their hands took their pherans and wrapped their shawls or blankets.

When the turn came for the assistant accountant to do so he was bewildered

to find his pheran clipped to shreds with a pair of scissors.

"Who is responsible

for the foul deed?" he shouted. There was a silence as every one of the

guests turned his attention to the victim.

"What foul

deed?" said the host.

"Who has heard

of respectable guests being exposed to such villainy in the house of the

host?" shouted the guest.

"No respectable

guest has been touched," answered the host, thus clearly holding a clue

to the mystery. "And" he continued, "as to the garment that has suffered

thus, I am convinced that it must be grateful to the scissors for having

been relieved of the unpleasant association with that body, for who has

heard of petty officials making themselves insolent and odd in the presence

of respectable gentlemen claiming nobility in birth for hundreds of years?

Who indeed has seen a humble clerk dressed in pashmina?"

"Are you referring

to my dress?" asked the guest. "If you mistake it for pashmina," he

continued, "you are deceived. I am a wage earner subject to rigours of

hard work. Mine is not the soft pashmina, the garb of the elite.

You could have spared yourself all this labour. The stuff is a mixture

of cotton and coarse wool, though it is well calendered and soft. Why did

you not satisfy yourself before having my pheran torn to shreds?"

There was confusion

among the guests but the host was heard repeating the words: "The upstart

will learn to keep his place. Somebody has misled him into giving himself

airs...."

|