Chapter

18

Counting

Ripples

Every

community has its predilections and prepossessions. The American businessman

is preoccupied with the interest on his investments. The retired British

soldier bores his club-mates with anecdotes of his years in active service.

Waking or asleep, the Japanese manufacturer can never divert his attention

from how to lower costs of production and capture foreign markets. The

Indian peasant talks tirelessly not so much of his wife and children as

of his lands, his bullocks, his landlord and the money-lender. The average

Kashmiri of the past, on the other hand, regarded government service in

whatsoever capacity as the choicest profession. Times have changed considerably

since the age to which the following tale belongs and the new breezes have

blown lofty ambitions into the minds of men and women; nevertheless, many

Kashmiris still love to picture themselves living in an atmosphere of grade

promotions, privilege leave, clerical mischief and executive authority.

Several generations

ago there was a young man of a respectable family. In those good old days

it was not necessary for all male members of a family to earn their living.

This particular young man, therefore, spared himself the discomfort of

burning midnight oil in pouring over his books or the toil of apprenticeship

in a profession. His family had inherited enough land for sustenance and

with a "devil-take-the-rest" air he felt that rudimentary literacy was

enough for his purpose. Nor did he have any occasion to resent his choice.

In course of

time he grew maturer in the fullness of experience. He realized that though

government employment carried very little by way of salaries or emoluments

it carried a great deal of prestige. People spoke to a government employee

much more respectfully than to one outside the pale of that privileged

circle, and with a little cleverness even the humblest of such employees

could earn a good deal without doing any serious harm to anybody. This

young man, therefore, made up his mind to seek government employment not

so much to make money as to command greater respect, to cut, as it were,

a figure in public who would say, "Here goes who wields considerable authority."

While he had

come to this conclusion independently, an incident occurred just about

that time which in his view made it imperative for him to seek employment

under the government. It appeared that his wife picked up a quarrel with

a neighbour whose husband was an accounts officer. This lady taunted her

adversary with the words that while her husband was a do-nothing drone

she was the wife of a respectable and trusted officer of the government

and added that she would realize the consequences of being discourteous

to her when her husband (the officer) would set into motion the machinery

of law and justice against her.

Pompous words

these! But the smaller wheels of law and justice somehow got into motion

and on several occasions her husband was asked to depose evidence or to

explain matters and it squared ill with his own notions of self-respect.

To secure a post in the State administration, therefore, became his greatest

concern.

Having thus

made up his mind he set about currying favour with the high-ups of the

time. In those days of autocratic rule the modern practice of looking into

budget provisions and securing financial concurrence was entirely unknown

and the ruler, or his viceroy, could confer any office on anybody or give

the sack even to the highest minister. But most rulers were conservative

and therefore slow in accepting suits for offices. This young man made

use of a number of agencies with this end in view and when at last he was

able to make his request known to the ruler, the latter appeared to him

to be unreasonably strict. What he could gather was that there was no post

to which he could be appointed.

He waited and

renewed his prayer to the head of the provincial administration, but with

no better prospect. Meanwhile, both he and his wife were burning with the

feeling of humiliation which had been heaped upon their heads by their

neighbour.The cold sighs of his wife were unbearable to him but obviously

there was no help. At last he approached the high-ups once again and explained

that his intention was not to secure necessarily a lucrative job; all that

he wanted, he elucidated, was to command greater prestige and respect and

that he would be satisfied even with a post that carried no salary. The

authorities who wanted to satisfy this young man were well pleased with

his offer to work without a salary. He had, however, little experience

of working in offices and it was found desirable to entrust him with a

task where he would not be in a position to interfere with the working

of other government agencies. They gave some thought to the problem but

could come to no definite conclusion. The young man renewed his suit and

offered to do anything, even "to count ripples on the surface of the river"

if he had the patronage of the government. They jumped at the suggestion

and at last the young man was offered a situation: his duty was to count

ripples. He welcomed this opportunity of gaining a foothold in the

world of officialdom and was well-satisfied for his pains.

When the offer

was first made it was done with the intention of filling his mind with

disgust. Who had ever heard of any gainful employment which comprised counting

ripples? And yet so eager was the seeker that he welcomed the offer. The

nature of his employment did not seem to dampen his enthusiasm even though

wags made fun of the nature of "august duties" entrusted to him. They roared

with laughter. "We have heard of star gazers," they admitted, "but 'counting

ripples' is an addition to the tasks of a civil government." Among those

who made ironical references to the new officer was his neighbour of the

accounts office.

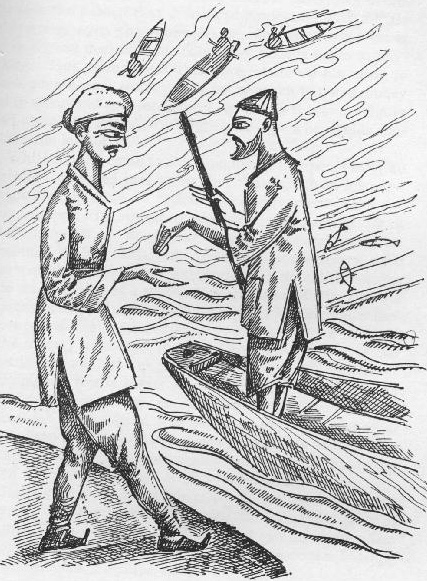

Despite all

this the young man assumed his duties seriously. Armed with a warrant of

appointment bearing the royal seal and equipped with a ledger and an encased

pen-tray-cum-inks/and (qalamdan) he posted himself in a doonga. In

those good old days the only conveyances on the roads were the pony or

the palanquin. Those who make use of cars or tongas today had their

own shikaras and the river was the main thoroughfare of traffic.

The young man, therefore. moored his boat near a bridge at the busiest

centre of this traffic, and he began to "count ripples."

In a few days

this news spread all over the valley. His business of "counting ripples"

was wildly talked of and People were left guessing as to the purpose behind

it. Meanwhile, the particular official felt his stock rising and began

to command greater respect. His wife at home regarded herself as respectable

as her neighbour. To this extent the mission of securing government employment

was fruitful. He recorded his observations in his books in the manner of

all clerks. But his ingenuity encouraged him to extend his authority to

fields about which his charter of appointment was silent. He urged all

boatmen to propel slowly without "disturbing the ripples." This was something

which they had never learnt all their lives, and they propitiated him,

for obviously he could get the movements of their boats stopped for quite

some time on the pretext of recording correct observations. Soon he found

that though his post carried no salary he was no loser. In fact, he made

a tight little sum every month and thanked the stars that made him "count

ripples."

Then came his

turn to flaunt his official authority in the face of his overweening neighbour.The

latter was proceeding along with his wife and children in a shikara to

participate in a wedding. They were dressed in their finest and the "counter

of ripples" got a brain wave to pay them in their own coin. When this particular

shikara was

within hailing distance of the bridge, he had it stopped.

"What is the

trouble?" the accounts officer puckered his brow.

"Nothing much,"

replied the other, "only that I want to discharge my duties correctly."

He started

counting ripples and recording his counts; recounting, checking and rechecking.

He took a really long time and yet his urgent government duty was not over.

He could not allow any boat to move and the wedding guests were hard put

to it. Time was galloping fast for the accounts officer, for both he and

his wife had to attend to important ceremonials at the wedding.

Equally important,

however, was it for the other officer to make correct observations and

the nature of his duties would not brook the least disturbance of the surface

of water! The wedding guest here beat his breast. Ultimately, however,

he saw into the whole business of counting ripples at that particular moment.

Both he and his wife took leave of their vanity, made up their differences

with their neighbour and lived at peace with the "counter of ripples."

|