Chapter

1

The

Precious Present

This story takes the reader to a village on the bank of the Wular, one of the

largest fresh water lakes in India. Many years ago the only approach to

the village was over mountain tracks or across the lake which though alluring

to the eye when placid is impassable when otherwise. Consequently the village

was practically cut off and no outsider visited it unless it was absolutely

indispensable for him to do so. Nor were the villagers very curious about

the rest of the world. God had given them enough land to grow maize, pulses,

and a few vegetables and the lake supplied them fish and water-nuts (caltrops),

the kernels of which formed their staple diet. There were the old shops

exchanging salt and cloth for dried fish, caltrops, maize and ghee, and

currency was hardly necessary. Coins were not in circulation in this remote

corner, and if ever they were, they were mostly of copper, or other lower

denominations. It was an age when even government officials were paid their

salaries mostly in kind, in terms of khirwars (ass-loads) of cereals. In

short, nobody in the village had ever seen the silver rupee with the effigy

of Victoria, Queen of Britain and Empress of India.

It so happened

that by some mysterious process a silver rupee of the above description

found its way into the village. It caused a great sensation there and everybody

was eager to have a sight of it. Before long the matter came to the notice

of the nambardar,

the headman, and the coin was handed over to him

for safe custody till he decided how to deal with this novelty. He pondered

over it for a day and a night, a pretty long day and a dark sleepless night,

and announced his decision the next morning.

"Brethren,"

he said, "this is the first coin of the kind that has ever been seen by

any one of us. It is stamped with the figure of our most respected ruler.

(At this his hand went involuntarily to his forehead by way of saluting

the ruler, listeners following suit.) God grant our ruler prosperity and

victory always, and humiliation to our enemies! It is most befitting that

we make a present of this respected and honoured token to His Highness

in person.... "

The proposal

was no sooner made than accepted. The headman of the village was regarded

as the wisest man. He gave them full details as to how such a present should

be placed before the ruler for his acceptance. The gift was to be placed

in a palanquin carried by six worthy elders of the village whom he nominated.

They got a really dainty palanquin and decorated it with whatever choice

cloth they could get. Spreading a finely woven blanket inside they covered

it with a piece of silk that somebody possessed. The headman then called

all the village elders to the palanquin. Young men and little urchins were

there already. In the presence of such an august gathering they placed

the rupee inside the palanquin and drew the curtains as if it carried a

delicate bride on her way to her husband's home. The capital was to be

reached by boat. A doongha stood ready at the quay equipped with

all requirements for the journey. The palanquin was lifted to the accompaniment

of delightful songs, portending success, sung by village women and deposited

gently in the doongha. The boatman pushed off and made for the south

where the capital lay, the villagers shouted their good wishes after it

and the headman gesticulated au revoir when the boat reached the

mouth of the river.

It is a tiresome

journey going upstream. The palanquin was given a seat of honour and nobody

could sit or stand with his back to it. At night they lit a lamp and kept

it alight till the dawn, and took their turns at the watch. Whoever asked

them the purpose of their journey south was told that they were carrying

a precious present for His Highness. They did not reveal the nature of

it at all.

On the morning

of the third day when they came to the outskirts of the capital they decided

to dispense with the boat and carry the palanquin on their shoulders. Barefoot,

with legs wrapped tightly with woollen puttees, and their backs

with cotton scarves in the manner of ancient courtiers, four of them lifted

the palanquin on their shoulders while one preceded it with a flag. The

headman walked humbly behind. They were all merry as befitted a deputation

waiting upon the ruler with a precious present and impressed every passerby

with their festive appearance. At the octroi-post the tax-collectors wanted

to have a look into the palanquin but the headman protested, saying, "Nobody

except His Highness will cast a look inside"; and the guards gave in.

The small procession

had to pass through the principal streets of the capital before they could

reach Shergarhi, the palatial residence of the ruler, built on the left

bank of the Jhelum. The news had spread fairly quick throughout the city

and many people were curious to know what precious gift it was that had

brought these doughty folk over such a long distance. The village folk

reached the palace gate and made their purpose known to the guards. The

captain of the guards got orders from His Highness to admit them within

and to show utmost hospitality. With loud shouts wishing victory and prosperity

to His Highness the little procession entered the gate of the palace. They

felt amply recompensed when treated as the guests of their ruler.

Within the

palace premises they, of course, displayed greater solicitude in according

respect and obeisance to the precious but secret gift inside the palanquin.

The guards and other palace officials were highly intrigued about the secret

but dared not ask them for fear of offending their sense of etiquette.

Meanwhile, the villagers fully basked in the lavish sunshine of the ruler's

hospitality and were keenly conscious of the honour which had schuss fallen

to their lot. "What reward will His Highness feel too high for us when

he receives us in audience and accepts the gift ?" whispered the headman

into the ears of the gratified elders.

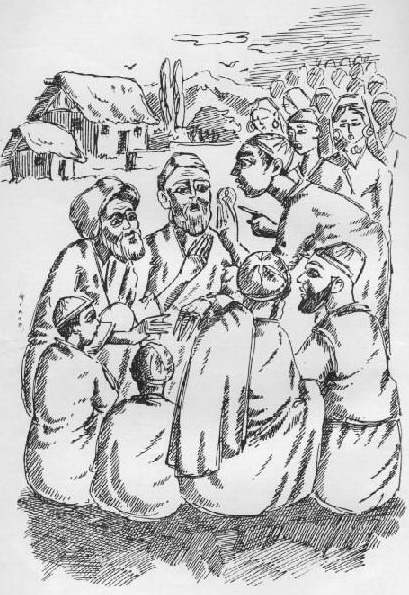

In the afternoon

His Highness got up from his siesta and: desired the elders to be admitted

to his presence. The -minister-in-waiting, the prime minister and other

dignitaries of the State were in attendance. The headman entered barefoot

and made obeisance. He was followed-':: by the elders bearing the palanquin.

"Sire !" began the headman "this humble servant who has the signal honour

of standing before his ruler and father is the nambardark of the

village...on the bank of the Wular lake, famous for its fish, caltrops

and deadly waves. Along with these men -who are worthy elders of the said

village this loyal servant has covered the distance with a happy heart

on account of the pleasant and honourable duty before us. We crave your

permission, our liege and father, to place this nazar at your Highness'

blessed feet."

"Our good men,"

returned the ruler, "we are touched hype your affection and loyalty which

prompted you to come from such a distant place to offer your nazar.

We

desire that it be placed before us."

The headman

drew the curtain and thrust his hand into the palanquin. He appeared to

be somewhat perplexed) and raised all the four curtains. Whispers were

exchanged by all the elders who began to fumble in the folds of theft blanket

and rummage into the corners of the palanquin) The nazar was not

forthcoming. Quite a few minuted passed thus while the villagers completed

a thorough search for the coin inside the palanquin. The primp minister

said, "Be quick rustics, His Highness has urgent matters of State to attend

to." But the rustics could not help the matter. In their rustic hilarity

they had so carried the palanquin as to suffer the precious gift to slip

somewhere. It was too late now to mend their folly and the headman made

the submission: "Our liege and father, we have unfortunately dropped the

nazar

somewhere

unwittingly."

The situation

thus took a serious turn. The ministers were of one mind in looking upon

the incident as an insult to the person and throne of the ruler. Punishment

could easily be awarded for such an act. "What astounds me," declared the

prime minister, "is the daring of these uncouth rustics. To come right

to the august presence of His Highness and try to cover their crime under

the frivolous excuse that they had dropped the nazar somewhere!

Your Highness, let them be taken to the prison and dealt with according

to law," he submitted.

The village

elders looked like sheep at the gate of the shambles though the headman

bore this sorrow with exemplary fortitude. "My head upon your Highness'

feet!" declared the headman turning towards the ruler, "make but a gesture

and this humble servant will offer his heart for you to feed upon. Who

is there so unworthy of his salt as to harbour anything but esteem, honour

and affection for our lord, liege and father! Who can be so daring as to

put his head into the mouth of a lion! Our Holy Book says that God Almighty

is Karim (merciful). I invoke your mercy, our respected father,

and seek permission to explain the whole case."

The ruler was

gifted with a good deal of commonsense. He saw at once that they were simple

but good-natured folk who had come from a remote village and meant nothing

but loyalty and affection. On the insistence of his councillors he devised

a plan to test their intentions. The villagers were placed in a cell and

were supplied with all requirements to enable them to cook their food.

Instead of being given a burning faggot or live coal they were given a

box of safety matches. They did not know what a match stick was and could

not cook their meal. They ate part of the rations raw and the rest was

kept intact.

When the ruler

heard this news through the captain of the guards he was convinced of their

innocence. He called the villagers, heard the whole story and had a hearty

laugh at their simple faith. He assured the headman that the gift was as

good as accepted. In fact he gave them a rupee and received it back as

nazar.

The

villagers felt highly gratified. Further, they were treated as guests once

again and dismissed the next morning with suitable gifts. In addition,

the land rent in their village was reduced. The villagers departed merrily

shouting slogans. Back in the village they narrated the tale about how

they had been saved from the very brink of destruction. The tale spread

to neighbouring villages and to remote ones till it was imprinted on the

minds of men.

|