Chapter

20

Akanandun

Long

long ago there lived a king. His principality comprised seven towns and

his capital was called Rajapuri. He was a kind and conscientious ruler

and dispensed justice with an even hand to high and low alike. He maintained

peace and his subjects lived happy and content under him. He was a god-fearing

man and his subjects held him in reverence as their father. He punished

with a severe hand all those who dared to trouble his subjects in the least.

He took measures for the welfare even of the birds and animals living in

his country. Ponds were dug to store drinking water for the quadrupeds

and troughs were placed on perches to enable birds to quench their thirst.

In all this he was assisted by able, honest and hardworking ministers.

His subjects

had but one longing and that was for the birth of an heir-apparent. The

king had but one queen who had borne him seven daughters. The king and

the queen were highly devoted to each other but craved for the birth of

a little brother to the seven sisters to gladden the hearts of the subjects

and their own. The Prince would shoulder the responsibilities of the kingdom

in time to come. Even his subjects begged God Almighty in their matins

and vespers to grant their ruler the gift of a little son, and the royal

couple did all in their power to secure such a coveted fruit. They gave

lavishly in charity which included gifts of land, garments, corn, livestock

and gold. Holy men from far and near came to Rajapuri to give their benedictions

to the queen who also met the expenses on the weddings of many destitute

girls and the maintenance of orphans and widows. Still the heir-apparent

of their dreams was as far away as ever.

The king except

when busy with the affairs of the State was always melancholy. "What good

is it for me to rejoice in my palace," he would brood, "when the line of

my illustrious ancestors will come to an end with my demise? Happy are

the poor beggars in my kingdom who look forward to the day when their sons

can relieve them of their burdens.... Were it not better for me to renounce

my throne and take to the life of an ascetic in the forests of the vast

Himalayas or in the cave of Shri Amarnath Ji. . . ?" He did not reveal

this corner of his heart to his consort lest she feel hurt. She, however,

had not given up hope and retained faith in holy men and ascetics.

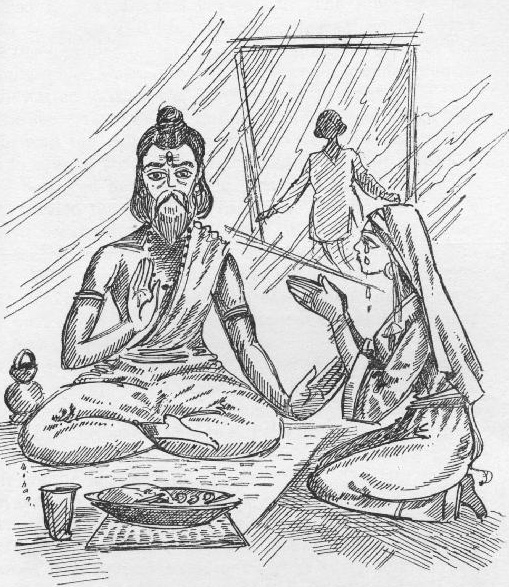

One day the

queen was sitting as usual in her chamber when she was startled by a call

for alms. It was nothing new for her who satisfied hundreds of such calls

every

month, but this time there was a peculiar lure and a strange tone in the

voice of the caller which demanded the personal attention of the queen.

She at once 'rushed to the courtyard. She beheld a jogi invested in an

expression of ecstasy. He had long locks of curly hair running down to

his back, his bare body was smeared with ashes and he had a clattering

wooden sandal under his feet. He had rings in his ears and his eyes were

sparkling. He carried a beggar's bowl in his hand and a wallet hung from

his shoulder. The queen requested him to name what would please him.

"Give me anything

in the name of God," replied the jogi. The queen told her consort that

the jogi was the very person whose aid should be enlisted in seeking

fulfilment of the age-long craving. She gave him a handful of precious

stones which he received in his wallet. The queen explained to him how

she was pining for a son. She said, "God gave us a kingdom to rule and

many rulers acclaim our suzerainty. But what is the good of all this splendour

when we have no male issue to look after it on our demise? Our seven daughters

will go their own way and bless the homes of young men unknown to us. Would

that they had a brother to shine in their galaxy as the sun! " she concluded

with a sigh.

The jogi listened,

apparently unmoved.

"With your

permission may I say something more?" asked the queen.

The jogi nodded

and the queen proceeded, "Only a few days back I saw in a dream a care-free

man resembling you. He patted me on the shoulder and assured me that my

longing would be fulfilled after nine months. O jogi, you alone

can interpret this dream."

Cutting the

matter short the jogi said that he would give them a son provided

they returned the child to him after twelve years. "The child will be yours

for twelve years if you promise that I can have him at the end of that

period," he said firmly. The king and his consort held consultations and

ultimately gave their promise that he could have the child back after twelve

years. On this solemn promise the jogi gave them the assurance that

their barren land would soon turn green and their longing for a male child

would be fulfilled even before their expectation. "Call the baby by the

name of Akanandun," he added, took a few strides and was lost to view.

In due course

the queen was conscious of motherhood once again. At first she kept it

a secret. When her consort made persistent inquiries she shared the secret

with him on the condition that he kept it to himself.

"It is none

else but Akanandun" said the king and rejoiced in his heart. "Was it God

or man who granted us the gift?" he added complimenting the jogi.

"Don't count

your chickens before they are hatched," cautioned his wife.

Nine months

being over the queen was in labour pains and was delivered of a male child.

"The jogi has indeed made his word good," said the king. There were

immense rejoicings in the whole country on the birth of the heir-apparent.

Thanks-giving services were held in temples and shrines, and people came

in large numbers to the ruler to offer their congratulations. Inside the

palace everyone was mad with joy. The king who already possessed a stout

heart for giving gifts was bountiful like a river. God had fulfilled his

heart's desire and he tried his utmost to see that nobody went away disappointed

from his door.

The baby was

brought up right royally. There were seven wet-nurses to feed him at the

breast. Their lullabies chanted melodiously sent him to sweet slumbers.

They rocked his cradle which was draped in velvet and cloth of gold, and

inlaid with gems. The baby was the dearest little creature ever born. His

eyes and eye-brows, his nose, his lips and chin, his forehead and complexion—

each in its own way betokened an extraordinary heredity for the little

infant who shone as the light of the palace. His sisters fondled him in

all affection and he was the apple of the eyes of his parents who were

ever grateful for his birth.

The baby grew

fast into a child and then a strong, handsome and intelligent boy. His

parents arranged for his education in a befitting manner. Akanandun, for

that is how they named the new-born as advised by the jogi, went

to school with his satchel and drank the learning deep according to the

fashion of the time. His teachers were not a little surprised at his acute

intelligence and sharp wit. The boy imbibed all that was worth knowing.

While everyone

looked hopefully to the future when the boy, in the fullness of his physical

strength and the maturity of his wisdom, would relieve his father of the

burden of ruling the State, there was one day a wild uproar in the streets.

"What is all this hue and cry about?" asked the passers-by and heard back

in whispers: "Twelve years are over and the jogi has returned to

claim the child." People talked with trepidation. "Was all this a dream?"

"And is the jogi really so callous as to deprive us of the young

prince?" "Will he blow out the lamp which is the only source of light in

the palace and abroad?"

Meanwhile the

jogi made his call at the palace and the ruler and the queen rushed out

to welcome him within. Their hearts were full with the debt of gratitude

for the jogi for the invaluable gift and they were only too eager

to do something to repay the debt to whatever extent. They solicited him

to take a seat of honour and to indicate what would please him.

He replied,

"I have come to seek fulfillment of the promise you gave. I have not seen

Akanandun for more than twelve years. Get him to my presence now."

"The child

has gone to the seminary. He will be here presently," said the queen.

"If you but

name a precious gift I would deem it a privilege to place it at your feet,"

submitted the father.

The jogi promptly

replied, "I have nothing to do with gifts. I simply want my Akanandun."

The parents

made many subtle attempts to beguile his mind, but to no purpose. These

attempts only enraged him. He called the child by name and the latter was

on the spot immediately. They submitted that he was the one who alone sustained

their lives and that their very existence was impossible without him. The jogi

was harsh and stern, "I have to kill Akanandun and you will rue it if you

try to dissuade me."

Everybody who

heard it burst into tears except the jogi. He divested the child

of his garments and ornaments. Warm water was got for cleansing his body

to which his mother had to attend. The child had a bright and radiant body

and the jogi had him dressed in bright new clothing. He had the

soles of his feet dyed in henna and applied collyrium to his bright

almond eyes. The child looked like a fresh-bloomed flower, but the jogi

had no time to waste. Proceeding forthwith to kill the child, he got a

butcher's knife. Everybody there cried but the jogi was entirely

remorseless. He laid Akanandun sprawling on the ground and asked his sisters

to catch hold of his limbs severally. There was a tremendous intensification

in the hue and cry raised. The king tore his tunic to shreds and his wife

rolled herself on the dust. But the jogi was remorseless and reminding

them of the promise given warned them of the inevitable consequences if

they tried to shirk the fulfillment of the promise.

The jogi

passed on the knife to the king and asked him to behead the child. Even

demons and monsters would fail to comply with such a commandment. But when

the king betrayed hesitation the inexorable jogi, overawing him,

pushed the knife into his hand. Finding that there was no escape the unlucky

father cut the innocent throat and scarlet blood welled out. The house

was turned into hell. Who was so petrified as to resist sobbing and crying?

There was beating of breasts, gnashing of teeth and pulling of hair. The

blood stained the walls, coloured the floor and dyed their clothes.

The involuntary

movement of the child's limbs having petered out, the jogi severed

them, had them washed and began to hack the flesh assiduously like a butcher.

When it was over he asked them to put the flesh into an earthenware vessel

and to boil it. Akanandun's mother attended to it smothering her sobs and

hiccoughs. The jogi warned her, on pain of dire punishment, not

to lose even the least particle of flesh. When the faggots were burning

bright, the jogi asked her to put the lid on. lie also got oil poured

into several cauldrons which were put on fire. The flesh was thus cooked

as if it were mutton, salt and spices being added according to need. The jogi

asked the queen to make haste as he was getting hungry. The lady could

suppress her feelings no longer and burst out upon him: "Which is the faith

that permits thee to eat human flesh? O stone-hearted jogi, how

have I ever offended thee? Aren't thou afraid of the curse of the innocent

sufferers?"

The jogi

replied, "O lady, I am indifferent to all the human weal or woe. You may

take me for a goblin or an ogre, but I have to fulfill my promise. So,

without prolonging the matter please attend to your cooking and tell me

how it tastes."

In spite of

her protests the unfortunate lady was forced to taste the soup. The jogi

asked her to pick out the flesh and to cool it as it was his wont not to

eat steaming dishes. He also asked for seven freshly baked earthenware

bowls. The bowls were got and he distributed the flesh evenly among them

all. The queen asked him what for he was dressing up seven bowls with flesh.

He replied promptly, "Four are meant for the female folk, two will suffice

us, two males, and one I am keeping for Akanandun."

This was a

blow which cut the queen deep in her heart. "How preposterously the fellow

speaks," she thought.

Meanwhile the jogi

passed on the bowls to the people for whom they were meant and turning

to the queen, said, "O lady, go and call Akanandun upstairs. I shall feel

really glad to see him and I can't taste a bit in his absence."

This was obviously

too much for her and she could not help saying, "O jogi, I completely

fail to fathom your mind. I have suffered the loss of my son, but have

not lost my wits yet."

The jogi

returned, "I'm not what you take me for, O lady; I constantly change my

deceptive appearances," and with that he gazed at the queen so that she

seemed to have been held in a vice.

When he again

asked her to call Akanandun from below she could not help going downstairs.

And when she called him by name she was surprised to hear, "Coming mother."

Anon he came to her as before, was held in fond embrace and carried upstairs

where another pretty bewilderment was in store for her. The jogi

was nowhere to be seen and the seven bowls of cooked flesh had disappeared.

|