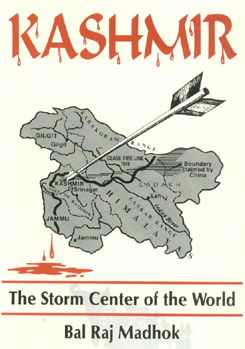

Chapter 10

The Dixon Proposals

The

Cease Fire eased the situation in so far as it put a stop to the actual

fighting. It also removed the fear of the fighting in Kashmir developing

into a general Indo- Pak War. But it did not bring the solution of the

problem as visualized by the UNCIP in its resolution of August 13, 1948

any nearer. Nothing had been settled about the Truce Agreement and plebiscite

which were to follow the Cease Fire in terms of that resolution before

India took the initiative to end the shooting War. This put the U.N. Commission

in a difficult position. While it appreciated India's self-abnegation in

stopping the actual fighting it could not allow the matters to rest there.

It, therefore, after waiting for a few months passed a new resolution on

January 5, 1949 which detailed the steps to be taken for the implementation

of the provisions of its earlier resolution about the Truce Agreement and

the plebiscite. To expedite the work it decided to move India and Pakistan

to carry on its mediatory efforts to that end.

But neither

Pakistan nor India was in a hurry to oblige the U.N. Commission. Pakistan

wanted to consolidate her position in the territories acquired by her and

was in no mood to take any risk by withdrawing the 30 battalions of local

troops raised from among the people of these territories and allowing the

writ of the lawful Government of Jammu & Kashmir to run, even nominally,

over the whole state on which India insisted. The divergence between the

views of the two sides regarding demilitarization and administrative control

over the territories occupied by Pakistan was so great that it took them

seven months even to finalize the Cease Fire Line.

The UNCIP therefore

began to veer round the idea of arbitration by a third party regarding

the disputed points about demilitarization which stood in the way of signing

of the Truce Agreement and induction of a plebiscite Administration for

which post the security council had nominated Admiral Chester Nimitz of

the USA. Accordingly, it presented to the Governments of India and Pakistan

on August 29, 1949 its proposal about submitting to arbitration their differences

regarding the implementation of Part II of the resolution of August 13,

1948. As if by prior arrangement, President Truman of the USA and Premier

Attlee of the U.K. wrote to the Prime Ministers of India and Pakistan about

the same time to accept this suggestion about arbitration.

party regarding

the disputed points about demilitarization which stood in the way of signing

of the Truce Agreement and induction of a plebiscite Administration for

which post the security council had nominated Admiral Chester Nimitz of

the USA. Accordingly, it presented to the Governments of India and Pakistan

on August 29, 1949 its proposal about submitting to arbitration their differences

regarding the implementation of Part II of the resolution of August 13,

1948. As if by prior arrangement, President Truman of the USA and Premier

Attlee of the U.K. wrote to the Prime Ministers of India and Pakistan about

the same time to accept this suggestion about arbitration.

The Government

of Pakistan accepted the suggestion but the Government of India rejected

it on the plea that the outstanding issue of disbanding and disarming of "Azad" Kashmir forces was a matter not for arbitration but "for affirmative

and immediate decision".

Though the

arbitration proposals thus fell through, it hardened the attitude of the

USA and the UK against India.

The U.N. Commission

therefore felt that any further efforts at mediation would be useless and

decided to return to New York and report its failure to the Security Council.

This it did on December 12, 1949. The majority report was signed by four

of the five members. While admitting the Commission's failure in the task

entrusted to it, it suggested that the "Security Council should designate

as its representative, a single individual who should proceed to the subcontinent

with the broad authority from the Council to endeavour to bring the two

Governments together on all unresolved issues".

Dr. Chyde,

the representative of Czechoslovakia, submitted a separate minority report

in which he charged the U.N. Secretariat, the USA and the UK with interference

in the work of the UNCIP, suggested that a new mediation organ really independent

and untrammeled by outside interference should be created and asserted

that the Security Council as a whole alone could be such an organ.

The presentation

of these reports and the charges levelled by Dr. Chyde about interference

by the U.S.A. and the UK in the working of the UNCIP made the division

of the Security Council between the Western and Eastern Bloc on the question

of Kashmir absolutely clear. It was now evident that the Kashmir issue

had got caught up in the cold war and that a dispassionate study and solution

of the problem on its own merits was going to become more and more difficult.

This fact began to further influence the foreign policy of the Government

of India in favor of the Communist bloc which in its turn made the attitude

of the Western bloc more and more sympathetic to Pakistan's point of view.

The security

council, after debating these reports for many weeks, decided by a majority

vote on March 14, 1950, to send a single U.N. representative to assist

in the demilitarization Programme and subsequent steps for organizing a

plebiscite. Sir Owen Dixon, a retired Judge of the Australian High Court,

was chosen for the purpose. Earlier, the names of Admiral Chester Nimitz

and Mr. Ralph Bunche were proposed but had to be dropped because of India's

opposition. The security

council, after debating these reports for many weeks, decided by a majority

vote on March 14, 1950, to send a single U.N. representative to assist

in the demilitarization Programme and subsequent steps for organizing a

plebiscite. Sir Owen Dixon, a retired Judge of the Australian High Court,

was chosen for the purpose. Earlier, the names of Admiral Chester Nimitz

and Mr. Ralph Bunche were proposed but had to be dropped because of India's

opposition.

Sir Owen Dixon

arrived in India 3n May 27, 1950. He immediately undertook a comprehensive

tour of Jammu & Kashmir State on both sides of the Cease Fire Line

and held discussions with local leaders besides the Prime Ministers of

India and Pakistan. On August 22, 1950 he announced that he had come to

the conclusion that there was no immediate prospect of India and Pakistan

composing their differences and that he would shortly report to the Security

Council. This he did on September 15, 1950.

Sir Owen Dixon's

report was the first judicial report on the state of Affairs in Jammu &

Kashmir as it had developed since the beginning of Pakistani invasion in

October, 1947. He made some practical suggestions about the solution of

the problem in the light of the actual realities of the situation on both

sides of the cease-fire Line.

He was the

first U.N. representative to state in unequivocal terms that the crossing

of the frontier of Jammu & Kashmir State by Pakistani invaders on October

22, 1947, and the entry of regular Pakistan Army into Kashmir in May, 1948

were contrary to international law.

He was again

the first U.N. representative to clearly grasp the fact that Jammu &

Kashmir State is just a heterogeneous conglomeration of territories under

the political power of one Maharaja and that it was not really a unit geographically,

demographically or economically. He, therefore, concluded that "if as a

result of one overall plebiscite the state in its entirety passed to India,

there would be a large movement of Muslims and another refugee problem

would arise for Pakistan. If the result favored Pakistan a refugee problem,

although not of such dimensions, would arise for India. Almost all this

would be avoided by partition. Great areas of the State are unequivocally

Muslims. Other areas are predominantly Hindu. There is a further area which

is Buddhist. No one doubts the sentiments of the great majority of the

inhabitants of these areas. The interests of the people, the justice as

well as avoiding another refugee problem, all point to the wisdom of adopting

partition as the principle of settlement and of abandoning that of an overall

plebiscite".

In the light

of above conclusions he suggested the following two alternatives to an

overall plebiscite:

(1) A plebiscite

be taken "by sections or areas" and the allocation of each section or area

be made according to the result of the vote.

(2) Without

holding a plebiscite, areas certain to vote for India and those certain

to vote for Pakistan "be allotted accordingly and the plebiscite be confined

only to the uncertain area". The "uncertain area" according to Sir. Dixon

appeared to be the "Vale of Kashmir and perhaps some adjacent country."

This plan of

holding a partial plebiscite in a limited area consisting of United Nations

officers headed by the Plebiscite Administrator with powers to "exclude

troops of any description. If however, they decided that for any purpose

troops were necessary, they could request the parties to provide them."

He further

suggested that the Security Council should pull itself out of the dispute

and let the initiative pass to the parties concerned. He, however, stressed

the necessity for the reduction in armed forces holding the cease-fire

Line to the normal needs of a peace time frontier.

Keeping in

view the actual state of affairs on both sides of cease-fire Line and the

Indian commitment about plebiscite to determine the will of the people

about accession, Dixon's proposals appeared to be eminently reasonable

and practical even though they militated against the legal and constitutional

right of India over the whole of the State. They left the gains of aggression

which included three out of the four Muslim majority regions of the State

in the hands of Pakistan and gave her a fair opportunity to secure control

over the fourth- the Valley of Kashmir - if the people of that region really

wanted to put their lot with her. They gave India an un-disputed control

over Jammu and Laddakh and provided her an opportunity to put the loyalty

of Sheikh Abdullah and Kashmiri Muslims for whom she had done so much,

to a fair test. To confine the plebiscite to the Valley with its small

and compact area was definitely to be preferred to an overall-plebiscite

in the whole of the State from every point of view.

But there was

one snag in these proposals. The suggestion to replace the lawfully constituted

authority in the Valley by the U.N. administrators with the right to invite

troops of both India and Pakistan if necessary for the purpose of maintenance

of law and offer could not be justified on any ground. It amounted to absolute

repudiation of India's special position emanating from the lawful accession

of the State to her and bestowal upon Pakistan, the aggressor who had already

obtained rich spoils, an equal status and right over Kashmir.

The Pakistan

Government rejected the Dixon proposals on the plea that they "meant a

breach on India's part of the agreement that the destinies of Jammu &

Kashmir State as a whole should be decided by a plebiscite taken over the

entire state". But this rejection was more tactical than genuine because

there could not have been a better proposal from the Pakistan point of

view.

But it was

not so easy for India to accept these proposals. It would have amounted

to an implicit acceptance by her that the accession of the State to India

had no legal and constitutional validity and that the State should be partitioned

on the same basis on which British India had been partitioned earlier.

Further, doubts had begun to assail the mind of Pt. Nehru as well about

the advisability of putting the Kashmiri Muslims into the ordeal of a plebiscite

in which, whenever held, religious and communal considerations would outweigh

all other considerations. Taya Zinkin, the representative of "Manchester

Guardian" of London, reported Pt. Nehru as having told her on June 30,

1950, in answer to her question whether he would accept the "status quo"

with plebiscite confined to the Valley of Kashmir, that he would not agree

to a plebiscite so long as Pakistan held a part of the State because the

people of Kashmir were "timorous." Pakistan had agreed that it would not canvass

in Kashmir on religious grounds but he could not run the risk of

their breaking this understanding. Compared with the risk of communal conflagration

he did not care about world opinion, but added that "of course if the Kashmiris

want a plebiscite to be fought on economic and not mind you, religious

grounds they can have it. But I shall never allow so long as I live a plebiscite

over cow's urine and all that. It would undo the whole of communal harmony."

1

However, according

to Sir Owen Dixon, the Prime Minister of India was in agreement with the

general principles underlying his proposals, viz., area where there was

no doubt as to the wishes of the people going to India or Pakistan and

plebiscite being confined to the areas where there was doubt about the

result of voting

provided the

demarcation line was drawn with due regard to geographical features and

requirements of an international boundary. But Nehru was strongly opposed

to Dixon's proposal about supersession of the existing Kashmir Government

and bringing in of Pakistani troops in the Valley if the plebiscite Administration

felt keeping of such troops there necessary.

There are reasons

to believe that had Sir Dixon and afterward the Security Council adopted

a flexible approach in regard to the suggestion about suppression of lawful

Kashmir Government and admission of Pakistan's troops into the valley if

the Plebiscite Administrator so desired, his proposals might have proved

a workable basis for a final settlement in spite of the immediate adverse

reactions of India and Pakistan to it.

But the Security

Council which met on February 21, 1951 to consider the report of Sir Owen

Dixon instead of finding out ways and means of making the Dixon proposals

acceptable to the two parties, decided by a resolution sponsored jointly

by the UK and the USA to send another U.N. representative to India and

Pakistan in succession to Sir Owen Dixon "to effect the demilitarization

of the State of Jammu and Kashmir on the basis of the demilitarization

proposals made by Sir Dixon in his report with any modifications which

the U.N. representative deems advisable, and to present to the Government

of India and Pakistan detailed plans for carrying out plebiscite in the

State of Jammu and Kashmir". This resolution was passed with slight modification

in spite of the opposition of India by a majority vote on March 30, 1951.

None voted against it but the USSR and Yugoslavia abstained.

In accordance

with this resolution the Security Council appointed Dr. Frank Graham of

the USA as its new representative for India and Pakistan. Dr. Graham who

first came to India and Pakistan in June, 1951 carried on endless discussions

with the Prime Ministers of both countries about the quantum of armed forces

to be retained by the two sides in Kashmir after a demilitarization in

terms of the resolution of August 13, 1948 had been brought about. Having

failed to make any headway, he suggested direct negotiations between the

two governments. They began at a joint conference of the two countries

at ministerial level at Geneva in August, 1952, and were later, after a

change of Government in Pakistan following the assassination of Prime Minister

Liaqat Ali Khan, continued at Karachi and New Delhi at the Prime Minister's

level.

The joint communiqué issued on August 20, 1953, after the conclusion of the talks

between the two Prime Ministers at New Delhi gave the impression that some

headway had been made toward a negotiated settlement. According to the communiqué

the Prime Ministers agreed to consider directly the preliminary

issues like the quantum of forces to be kept by both sides in Kashmir and

to that end decided to appoint military and other experts to advise them

in regard to these issues. A provisional time-table for implementation

of their decisions was also drawn up according to which the Plebiscite

Administrator was to be inducted into office by April, 1954.

But before

any concrete steps could be taken to implement the decisions announced

in the joint communiqué, a new turn was given to the whole problem by the

military pact between Pakistan and USA under which Pakistan began to receive

massive military aid from the USA and the internal developments in Kashmir

which culminated in the overthrow of Sh. Abdullah and installation of a

new Government headed by Bakshi Gulam Mohammed and ratification of accession

by the Kashmir Constituent Assembly.

FOOTNOTE

1. "Reporting

India" by Taya Zinkin, Pg. 206.

|

party regarding

the disputed points about demilitarization which stood in the way of signing

of the Truce Agreement and induction of a plebiscite Administration for

which post the security council had nominated Admiral Chester Nimitz of

the USA. Accordingly, it presented to the Governments of India and Pakistan

on August 29, 1949 its proposal about submitting to arbitration their differences

regarding the implementation of Part II of the resolution of August 13,

1948. As if by prior arrangement, President Truman of the USA and Premier

Attlee of the U.K. wrote to the Prime Ministers of India and Pakistan about

the same time to accept this suggestion about arbitration.

party regarding

the disputed points about demilitarization which stood in the way of signing

of the Truce Agreement and induction of a plebiscite Administration for

which post the security council had nominated Admiral Chester Nimitz of

the USA. Accordingly, it presented to the Governments of India and Pakistan

on August 29, 1949 its proposal about submitting to arbitration their differences

regarding the implementation of Part II of the resolution of August 13,

1948. As if by prior arrangement, President Truman of the USA and Premier

Attlee of the U.K. wrote to the Prime Ministers of India and Pakistan about

the same time to accept this suggestion about arbitration.

The security

council, after debating these reports for many weeks, decided by a majority

vote on March 14, 1950, to send a single U.N. representative to assist

in the demilitarization Programme and subsequent steps for organizing a

plebiscite. Sir Owen Dixon, a retired Judge of the Australian High Court,

was chosen for the purpose. Earlier, the names of Admiral Chester Nimitz

and Mr. Ralph Bunche were proposed but had to be dropped because of India's

opposition.

The security

council, after debating these reports for many weeks, decided by a majority

vote on March 14, 1950, to send a single U.N. representative to assist

in the demilitarization Programme and subsequent steps for organizing a

plebiscite. Sir Owen Dixon, a retired Judge of the Australian High Court,

was chosen for the purpose. Earlier, the names of Admiral Chester Nimitz

and Mr. Ralph Bunche were proposed but had to be dropped because of India's

opposition.

No one has commented yet. Be the first!