|

Milchar

October-December 2002 issue

|

|

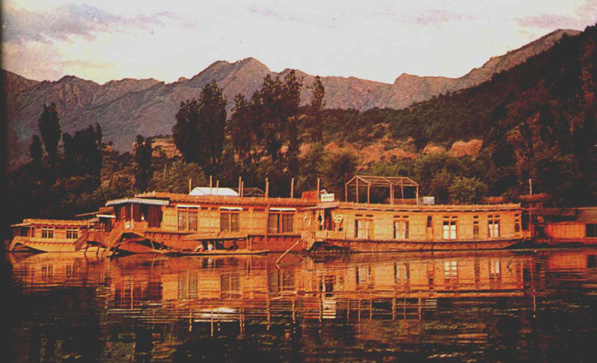

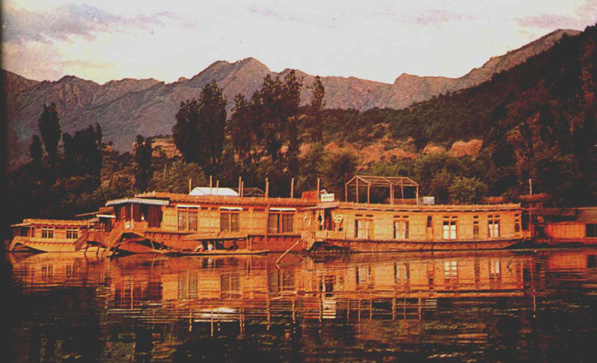

House Boats on Dal

Lake in Srinagar. Credit for introducing

House Boats in Kashmir goes to Pt. Narain Das, father of Swami Laxman ji.

|

|

|

|

Eve's

Corner

Position

of Women in Ancient Kashmir

... Sonia Raina

Down

the ages, Kashmiri women have been extolled as the best specimen of oriental

beauty. James Milne in Road to Kashmir, characterised a Kashmiri woman

as a 'primal creature in her Garden of Eden'. Kashmiri women however, witnessed

varying fortunes, largely due to politico-social upheavals, much too frequent

in the medieval period. During the dark periods, they were pressurised

with servitude and deprivation. Their activities got confined to the four

walls of the house. This seclusion sapped their intellectual curiosity

and artistic creativity. In periods of comparative reprieve, some of them

fought valiantly against injustices and were able to leave an enduring

imprint on Kashmir's annals. Down

the ages, Kashmiri women have been extolled as the best specimen of oriental

beauty. James Milne in Road to Kashmir, characterised a Kashmiri woman

as a 'primal creature in her Garden of Eden'. Kashmiri women however, witnessed

varying fortunes, largely due to politico-social upheavals, much too frequent

in the medieval period. During the dark periods, they were pressurised

with servitude and deprivation. Their activities got confined to the four

walls of the house. This seclusion sapped their intellectual curiosity

and artistic creativity. In periods of comparative reprieve, some of them

fought valiantly against injustices and were able to leave an enduring

imprint on Kashmir's annals.

Women in Kashmir were not only equal but

considered a little superior in many spheres of mundane life. Abhinavagupta,

the versatile exponent of Shaivist philosophy says that according to the

creed 'a man must have a woman as a messenger for communication with the

All Powerful, who must be treated as one's equal and with honour, otherwise,

he forfeits his rights to perform religious ceremonies and rituals laid

down by the Shaivist preceptors'.

Regarding the position of women in early

Kashmir, we learn that the first part of a woman's life was spent in her

father's house, when liberal education was imparted to her. Bilhana, the

poet laureate of 11th century A.D. says that even the women in their household

spoke Sanskrit and Prakrit as fluently as their mother-tongue. Women, at

least of upper classes received education in diplomacy and state craft,

besides that of general nature like biological sciences, arts, music, singing,

dancing & painting.

There is no indication of women being in

seclusion or relegated to the background. The use of the veil was non-existent.

Women could hold property in their own right. A passage from the Rajatarangini

tends to show that after the death of her husband, the widow became heir

to his immovable properties and not his sons.

Women enjoyed equal rights as men in the

affairs of the state as also in the discharge of public duties. This is

amply proved by the anointment of queens along with their husbands at the

time of coronation. They fought alongside men on foot or on horseback.

There is evidence that wise women made their husbands' rule a success.

Queen Suryamati made judicious selection of ministers and other officials

to

give public confidence in her otherwise weak husband, King Ananda. He was

later made to abdicate in favour of his son. Didda dominated her weak husband

Kshemagupta. She controlled the destinies of the kingdom as regent and

a queen for half a century.

The great success with which Didda and

Sugandha governed their dominions, naturally presupposes that they were

put in the way to efficiency by some previous instruction and practice.

Heroism displayed by Didda and Kota Rani was exemplary. Queen Kalhanika

went at the head of an emissary to bring rapprochement between Bhoja and

Jayasimha. Women of a lesser status too appear to have taken leading part

in the political activities of the State.

Regarding the proper age of marriage of

a woman, no positive evidence is forthcoming. A perusal of the Rajatarangini

generally leaves the impression that pre-puberty marriage probably was

not in vogue in ancient Kashmir. A story related by Kshemendra in the Desopadesa

may indicate that girls were married at a mature age.

Widows were expected to live a pure life,

devoid of luxury. The use of ornaments or gorgeous dress was forbidden

to her. Remarriage of widows and of other women does not seem to have been

absolutely forbidden. Partapditya II married the wife of a rich merchant.

Kota Rani's remarriage after Rinchana's death is well known.

The custom of burning of Sati was in vogue

in Kashmir from an early time. In the stories of Kathasaritsagara, which

was composed in the valley in 11th century A.D., the custom appears to

be quite common. About the historical cases of widows burning themselves

at the death of their husbands, we have a number of instances in Rajatarangini.

The custom of Sati was so deep rooted in the valley that even mothers and

sisters and other near relatives burnt themselves along with their beloved

deceased. Gajja cremated herself with her son Ananda, Vallabha with her

brother-in-law Malla, and the sister of Dilhabhattaraka cremated herself

with her brother. The custom persisted long after the Hindu rule till Sultan

Sikander banned it.

[Sources:

1. Early History & Culture of Kashmir

by S.C.Ray.

2. Kashmiri Pandits - A Cultural Heritage.

3. Culture & Political History of

Kashmir by P.N.K.Bamzai.

4. Information Digest Vol: 1 - Project ZAAN]

| |

|

|

Down

the ages, Kashmiri women have been extolled as the best specimen of oriental

beauty. James Milne in Road to Kashmir, characterised a Kashmiri woman

as a 'primal creature in her Garden of Eden'. Kashmiri women however, witnessed

varying fortunes, largely due to politico-social upheavals, much too frequent

in the medieval period. During the dark periods, they were pressurised

with servitude and deprivation. Their activities got confined to the four

walls of the house. This seclusion sapped their intellectual curiosity

and artistic creativity. In periods of comparative reprieve, some of them

fought valiantly against injustices and were able to leave an enduring

imprint on Kashmir's annals.

Down

the ages, Kashmiri women have been extolled as the best specimen of oriental

beauty. James Milne in Road to Kashmir, characterised a Kashmiri woman

as a 'primal creature in her Garden of Eden'. Kashmiri women however, witnessed

varying fortunes, largely due to politico-social upheavals, much too frequent

in the medieval period. During the dark periods, they were pressurised

with servitude and deprivation. Their activities got confined to the four

walls of the house. This seclusion sapped their intellectual curiosity

and artistic creativity. In periods of comparative reprieve, some of them

fought valiantly against injustices and were able to leave an enduring

imprint on Kashmir's annals.