The Land of Rock

Ladakh - the land of many passes

The Srinagar-Leh

road, skirting the banks of the Drass river reveals a canvas full of colours,

painting a soulful harmony. It composes a moment when Nature is in creation.

Once past the Zoji-La (pass), the change is dramatic

and stark. The green valley suddenly becomes barren and awesome. The air

gets brisker, the sun warmer. And before you is a gigantic sculpture in

desolate rock, silencing the mind and compelling the imagination to stand

back and gaze in awe at this vast expanse of solitude.

Now you are a little closer to the skies. The

once forbidden land of Ladakh unfolds itself. An amazing land, top of the

world.

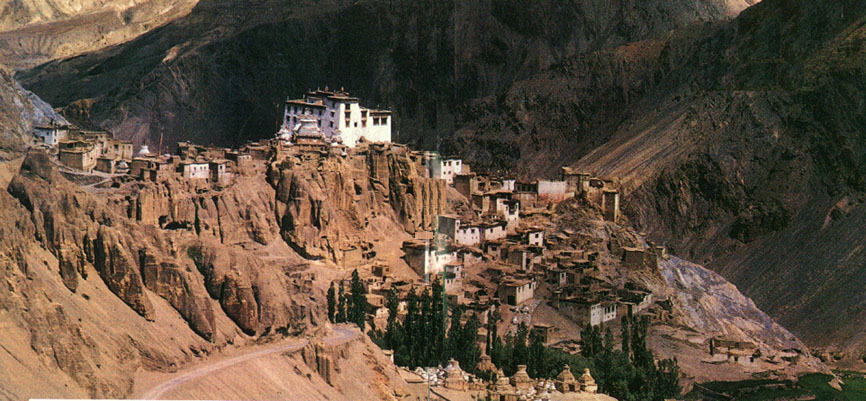

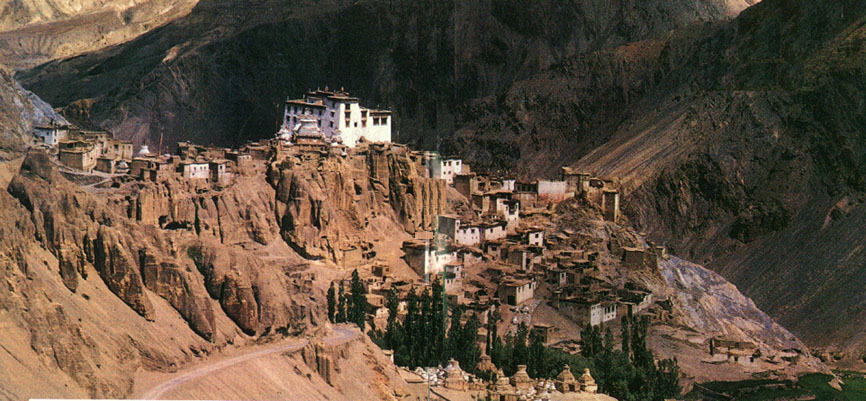

The small villages, with towering edifices of

granite and gravel mountains encompassing them, look frail and inconsequential.

This is Ladakh - the land of rock.

Ladakh - the land of many passes, of freezing

high barren landscapes lying across the lofty Asian tableland - is among

the highest of the world's inhabited plateaus. Remote yet never isolated,

this trans Himalayan land is a repository of a myriad cultural and religious

influences from mainland India, Tibet and Central Asia.

Situated on the western end of the Himalayas,

Ladakh has four major mountain ranges - the Great Himalayan, Zanskar, Ladakh

and the Karakoram - passing through it. A maze of enormously high snow

capped peaks and the largest glaciers outside the polar region, dominate

the terrain where valley heights range from a mere 8,000 feet to 15,000

feet while passes of up to 20,000 feet and peaks reaching above 25,000

feet can be seen all around. The world's largest glacier outside the polar

region, Siachen is here. Such daunting heights no wonder determine the

land's temperature where Leh and Kargil experience temperatures as low

as - 30° C and Dras -50°C. Three months of sub zero temperatures

(Dec-Feb) and the, rest of the months facing zero degree temperatures,

it is a long and hard winter here. Waterways, waterfalls and lakes freeze,

and the water vapour freezes to break into the most intricate and

attractive crystal patterns. But on clear sunny days, when the average

temperature goes over 20° C, the sun can be scorching hot in its intensity

and its ultra violet rays cause deep sun burn. Rainfall is a mere 2 inches

and it is the melting snow in summer which sustains life in this arctic

zone. High aridity and low temperatures lead to sparse vegetation as a

result of which the landscape is desert-like with sand dunes and even occasional

sand storms occur.

The major waterway of Ladakh is the Indus which

enters India from Tibet at Demchok. Starting near Mt. Kailash, the Indus,

according to mythology, sprouts from the mouth of a lion, and is therefore

known as Sengge Chhu. Sengge (Sinh in Sanskrit) means lion and Chhu is

Tibetan for a flowing water body.As it flows down, Sengge Chhu is joined

by its other tributaries, the Zanskar, the Shingo and the Shyok, and these

river valleys form the main area of human habitation.

Ladakh also has one of the largest and most beautiful

natural lakes in the country. Pangong Tso, 150 km long and 4 km wide, is

nearly an inland sea at a height of 14,000 feet, with intensely clear water

of an incredible range of hues of blue. Having no outlet the water in the

lake is highly brackish and the lake's basin houses a large wealth of minerals

deposited by the melting snows every year. Tso Moriri, a pearl shaped lake,

and Tso Kar, both contain large mineral deposits. Among the fresh water

lakes Yaye Tso, Kiun Tso and Amtitla offer great scenic attraction.

Ladakh, though a remote border land with virtually

no surface communication for more than six months a year, has surprisingly

never been isolated. Continuous cultural and commercial contact existed

with the surrounding regions of Tibet, Himachal, Kashmir, Central Asia

and Sinkiang. This interaction helped maintain trade ties between the places.

Pashm, salt, borax, sulphur, spices, brocade, pearls, metals, carpets,

tea and apricots were the merchandise exchanged in their marts.

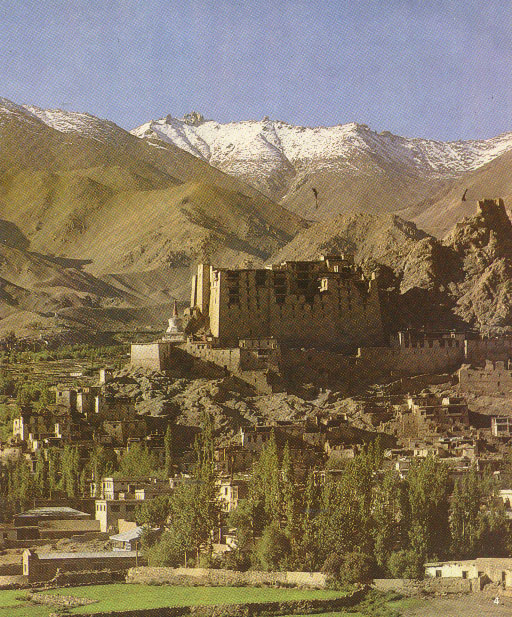

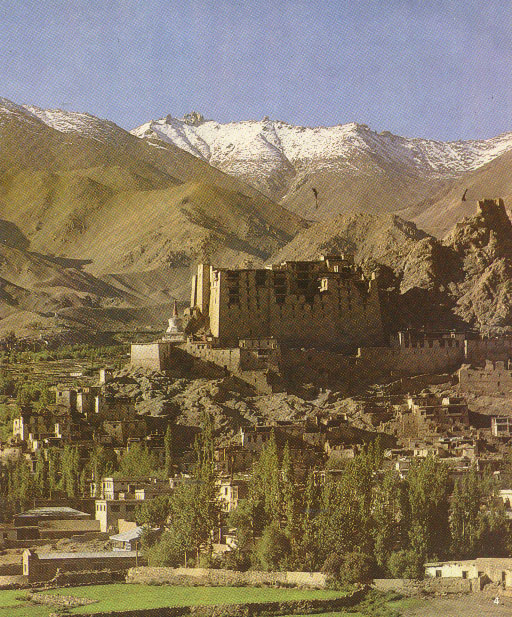

The Leh Palace, standing like a sentinel,

overlooks the town

Covering an area of approximately 98,000 sq km,

Ladakh has a sparse population of about 1,35,000. All habitations are situated

along water courses, where long distances are traversed by using animal

transportation of mainly the yak and the pony, the broad backed hunia sheep

and the Bactrian two-humped camel. Ethnically, the Ladakhis comprise an

amalgam of four prominent strains, namely the

Mons,

Dards, Tibetans and

Baltis. Mons belong

to the Aryan race. They might be called professional entertainers, as they

move from place to place playing their musical instruments and for the

most part are denied the privilege of inter-marriage with the other groups.

Dards are confined mainly to Dras and the Indus Valley. At Dras, they are

Muslims and retain very little of their past. But those in the Indus valley

below Khalsi display a distinctive identity, preserving their original

Buddhist religion as well as their cultural entity.

The Tibetans are the dominant racial strain in

eastern and central Ladakh, but over the years have merged with other groups

to form a homogeneous Ladakhi entity. Two ethnically and culturally distinctive

groups are the Tibetans proper living at Choglamsar and the nomadic Changpas

with their herds of pashm bearing goats in the eastern plains.

Baltis are mainly found in western Ladakh in the

Kargil region, but isolated pockets exist in the Nubra valley and near Leh. They are believed to be descendants of the Sakas, a Central

Asian race.

All groups have together contributed their own

perceptible share in the distinctive physiognomy, language and homogenised

culture of Ladakh. The Ladakhis are a simple and hardy people with an immense

capacity for work and the fortitude to not merely survive but remain cheerful

under the most adverse physical conditions. Living as close to nature as

they do, they have maintained a harmonious balance with their surroundings.

Acknowledgments

|

No one has commented yet. Be the first!