May-June 1998

Vol. II, No. 7 & 8

'Unmeelan' proves to be an eye-opening

event

The first ever exhibition on Kashmiri

Pandit cultural heritage leaves people spellbound

On April 12, 1998, people in the national

capital opened their eyes on glimpses of the cultural and artistic heritage of

the Kashmiri Pandits shown by NSKRI at an exhibition at AIFACS, New Delhi.

Titled 'Unmeelan', the exhibition was opened to public view by Dr. Lokesh

Chandra, eminent scholar. And what people, who thronged the exhibition on all

the four days it remained open, were shown, left them literally rubbing their

eyes with wonder. It may not have exactly taken Delhi by storm, but the event,

the first of its kind to have ever been organised, did intellectually stimulate

and inspire art lovers and the aesthetically inclined as well as those

culturally interested in Kashmir.

As Dr. Lokesh Chandra lit the ceremonial

lamp to inaugurate the exhibition, a forgotten but fascinating world of culture

came alive with rare and beautiful miniature paintings of the Kashmir School,

old Sharada and Persian manuscripts, letters and documents relating a saga of

scholarship, artefacts and articles of daily and ritualistic use, costumes and

folk art patterns and old photographs of social and religious gatherings

unfolding unexplored and unknown dimensions of Kashmiri Pandit cultural life.

Speaking on the occasion, Dr. Lokesh

Chandra said that the Kashmiri Pandits had played "a major role in the

transformation of India's thought process." Kashmir, he said, was the

"crown of India from where culture eminates." There are inscriptions,

he said, which reveal that the great temples of Khajuraho were built in

accordance with the guidelines laid down by the Kashmiri Pandits in their

Tantras.

According to Dr. Lokesh Chandra, "the

Kashmiri Pandits were not only gifted but they were also equally

adventurous." Giving examples of their genius and their adventurous spirit,

he said that they went to Central Asia, Tibet, China, Korea, Japan and

Phillipines for the dissemination of Indian culture, art and philosophy.

"In Japan the Lotus Sutra is

considered to be the greatest and most popular Sutras of Buddhism today,"

Dr Lokesh Chandra said. "And this Sutra was translated into Chinese in the

4th century by Kumarjiva who was a Kashmiri. His father was from Kashmir and his

mother, a princess of Kucha in Central Asia. He is regarded as the greatest

Indian stylist of Chinese prose, and one of the eminent Chinese writers. Only

four of five years ago the Chinese erected a special monument to Kumarjiva,

instituting a very big prize for people who are associated with the cult of

Kumarjiva.

"Kumarjiva's father had gone for

trade to Kucha. On his way, he stopped at Kashgar, came to Kashmir and then went

to Kucha. He left his wife and a son was born to them. His mother declared that

she would take the same route to Kashgar, which was called Kashi in ancient

times. Even today the Chinese call Kashgar Kashi. That was the place where the

Kashmiri Pandits taught the Vedas. Then when they wanted to have the study of

Vedangas and other higher subjects, they came to Kashmir."

Dr. Lokesh Chandra referred to yet another

gift of the Kashmiri Pandits to Japan --Siddham calligraphy. "There is a

tradition in Japan to write Sanskrit shlokas in a very beautiful script called

Siddham," he revealed. "It is a major art in Japan and the Japanese

learnt this art from two great Kashmiri Pandits, Prajna and Munishri. Even today

there is practically no house where you don't find something written in Siddham."

Dr. Lokesh Chandra explained that "the ink that is taken to write one bija

or akshara cannot be replenished. So you have to take sufficient ink to write

that particular mantra. Special dresses are created to write these mantras

taking into account the size of the character. So Kashmir has given a sense of

tremendous beauty to the people of Japan".

According to Dr. Lokesh Chandra, there is

hardly any place in South East Asia where Kashmir is not spoken of as the land

of scholars. "They went to Japan, they went to Korea, they went to

Phillipines", he said. "A number of Kashmiri Pandits", he

disclosed, went to Korea. Tyagabhadra, a Kashmiri, and his disciples were

responsible there for the choice of the present capital of South Korea -- Seol."

There was a period in the 14th century

when the Mongols were ruling over Iran, said Dr. Lokesh Chandra, giving another

example of the role of Kashmiris in the propogation of Buddhism. There were a

large number of Buddhist monastries in Iran at that time, and this is confirmed

by several Persian and Arabic texts, he pointed out. "The Americans have

made an aerial survey of the Buddhist monastries in Iran, but the results were

never published because it is a politically volatile subject", he revealed.

Just before the Islamisation of the Mongols there, the Khan wanted someone to

write an account of their history and their religion. And this task, according

to Dr. Lokesh Chandra, was accomplished by a Kashmiri Pandit named Kamalshila,

who was the royal chartsman of the Mongols.

Dr. Lokesh Chandra further disclosed that

in Mongolia proper, Kashmiri Pandits brought the Shilpashastras or canons of

creation with them for which they were given free access to the Mongolian court.

These canons were based on the aesthetic ideals of the human body or the body

modulations stipulated by the Kashmiri Pandits and are followed in Mongolia, in

parts of Western Tibet as well as in Kashmir. It is Kashmiri artists who

decorated the huge walls of monastries in Western Tibet in the 10th century, the

learned scholar said, and also at Kabo in Lahul, Himachal Pradesh. Alchi in

Ladakh was decorated with murals later. In this connection, Dr. Lokesh Chandra

referred to a Sharada inscription which, according to him, "could give clue

to the whole transmission of art in Western Tibet."

"That is why the Pandits from Kashmir

were held in great affection throughout history", Dr. Lokesh Chandra

observed. "Whether it was in Centra Asia, whether it was in China, whether

in Japan, the Kashmiri Pandits played a very important role in spreading

Buddhism and Indian culture", he said, concluding his illuminating speech

which the audience listened with rapt attention. He expressed the hope that

Kashmir would again hum not only with music, but also with great culture,

provided the Pandits made a resolve like the Jews made during their diaspora. He

was happy, he said, that an institution like the NSKRI had been started which

accepted the Sanskritic tradition. "You have rejected everything that was

yours", he pointed out, and it is that rejection that is responsible for

the situation in which you find yourself today. You have to make up and say that

you will react to every negative thought", he concluded, amidst thunderous

applause.

Presiding over the inaugural function,

Shri J. N. Kaul, SOS Childrens' Villages of India and President of the All India

Kashmiri Samaj, referred to the present predicament of the Pandits and said that

the Kashmiri Pandits had passed through many difficult phases in their history.

"But inspite of all these happenings, I think we are on the way to further

advancement. We have earnestly sought not only physically but also

intellectually our place under the sun. Normally, under the circumstances which

we have faced, our culture should have been wiped off, but we have always had a

rebirth and we have flourished." Shri Kaul said that it was his firm belief

that "the Kashmiri Pandit is bound to lead. He is bound to lead by his

destiny, by the circumstances of his life, so he must prepare himself for a

better performance." He regretted that the Kashmiri Pandits have never been

recognised because of their small numbers. "But", he said, "in

the circumstances in which we have been thrown today, we have to assert

ourselves. We have to say where we are in our journey and put it before the

nation. We have always been taught to keep our heads low while talking -- 'nemni-kremni'

as the Kashmiri phrase goes. But our children must walk with their heads

high."

Lauding the NSKRI for having undertaken to

work "in a very important field", Shri J. N. Kaul said that the

Institute has been named after a great scholar, Nitvanand Shastri." but

there are many Shastris, some of whom may even be sitting here, who are waiting

to be re-discovered". Shri Kaul "complimented" the NSKRI

"for this beautiful work" ('Unmeelan').

Earlier, in his introductory address, Dr.

S. S. Toshkhani said on behalf of the NSKRI that the exhibition was "an

attempt to present the real cultural face of Kashmir -- a face that has been

long kept away from view". He regretted that "a state of amnesia is

today clouding the minds of the people about the role that the Kashmiri Pandits

have played in shaping the country's cultural and civilizational history."

"It is they", Dr Toshkhani pointed out, "who evolved some of the

seminal ideas and concepts that stimulated intellectual and creative activity in

ancient India. Mahayana has been their greatest gift to Buddhism, while Kashmir

Shaivism represented one of the greatest heights that Indian philosophical

thought has attained", he said. "In fact contrary to the general

impression that they remained cut off due to geographical isolation, the Pandits

of Kashmir crossed their mountain barriers to unite north and south India

through Shaivite thought."

Referring to the Kashmir school of art,

Dr. Toshkhani said that it had a deep impact on the adjoining Himalayan regions

and was one of the principal formative forces of Lamaistic art. "Can there

be anything more tragic than this that inheritors of this great cultural legacy,

the descendants of the ancient people of the Nilamata Purana, are today facing a

sinister threat of cultural extinction?" he asked. The NSKRI has been set

up to protect and project the cultural heritage of the Kashmiri Pandits, he

said, 'Unmeelan' being the first in a series of thematic exhibitions which the

Institute was going to organise in the near future.

Offering the vote of thanks on behalf of

the NSKRI, Shri P. N. Kachru complimented all those who offered their valuable

cooperation in making the event a success.

Unmeelan Glimpses of Kashmiri Pandit

Cultural Heritage

Introductory Address by Dr. S. S.

Toshkhani

Respected Dr Lokesh Chandra, Shri J. N.

Kaul and distinguished guests,

It is, indeed, a great privilege to

welcome you all on behalf of the NS Kashmir Research Institute to this first

ever exhibition on Kashmiri Pandit cultural heritage titled 'Unmeelan'. The word

'Unmeelan' means 'opening the eyes', and this exhibition is literally an

invitation to opening of eyes if only to have a glimpse of the heritage of the

Kashmiri Pandits, a people who have contributed most significantly to Indian

culture, philosophy, literature, art and aesthetics quite out of proportion to

their small numbers. That these people stand uprooted today from their native

soil and are fighting a grim battle for their survival as a distinct social and

cultural entity, is perhaps the greatest tragedy in the history of

post-independence India. There is every danger that these ancient people may be

wiped out of existence together with five thousand years of their culture and

traditions, their literature and lore. And, if such a catastrophe does take

place, prosterity shall have much to regret.

It is most unfortunate that a state of

amnesia is clouding the minds of people about the role that the Kashmiri Pandits

played in shaping the country's cultural and civilisational history. It is they

who evolved some of the seminal ideas and concepts that stimulated intellectual

and creative activity in ancient India. Is it to be forgotten that Mahayana has

been their greatest gift to Buddhism, a doctrine that penetrated into and swept

across entire Central Asia, South Asia and the far eastern countries through the

efforts of Kashmiri missionaries? One such missionary, Shyam Bhatt devised a

script for the Tibetan language and gave it its first grammar. Does not Kashmir

Shaivism represent one of the greatest heights that Indian philosophical thought

has attained? In fact, contrary to the general impression that they remained cut

off due to geographical isolation, the Pandits of Kashmir crossed their mountain

barriers to unite north and south India through Shaivite thought. In the same

manner, Shaktivad and the Tantric philosophy evolved in Kashmir linked the land

of Vitasta with Kerala in the south and Bengal in the east. Surely, the best in

Sanskrit literary tradition bears an indelible stamp of the genius of Kashmiri

Pandits. It was Kalhana who started the tradition of histriography in India with

his immortal work, the Rajtarangini, displaying a keen sense of history and

sharp critical talent. Kshemendra, one of the sharpest critics of men and

matters, was the first Sanskrit writer to have made satire as his main mode of

expression. Somadeva's Kathasaritsagara is one of the world's most wonderful

collection of tales comprehending a wide range of myth and mystery, fun and

frolic, love and lust, ambition and adventure, cowardice and chivalry.

And what remains of Sanskrit aesthetical

writing if Kashmir's contribution to it is taken out? The inquiry into the

nature of aesthetic experience by such master minds from Kashmir as Bhamah,

Udbhatta, Vamana, Rudratta, Kuntaka, Anandavardhana, Mammatta, and the greatest

of them all Abhinavagupta, soared, in the words of Krishna Chaitanya, "into

philosophy risen from the world of poetry to a poetic world-view".

In the field of Indian music, one of the

most important treatises ever written is Sharangadeva's Sangeet Ratnakara - the

work which formulates the basis of Karnataka music and has few other works in

the world to compare with it.

In the history of Indian art, Kashmir

occupies a very important place, drawing to it all the power and beauty of the

Gandharan and Gupta art, and at the same time evolving a distinct metaphor and

style of its own. The Kashmir school of art had a deep impact on the adjoining

Himalayan regions and was one of the principal formative forces of Lamaistic

art. In the 9th to 11th century Kashmiri artists were producing exquisite

bronzes and painting murals in Alchi (Ladakh), Western Tibet and Spiti (Himachal

Pradesh). The grandeur of Martand and Avantipur temples testifies to the heights

of glory which Kashmiri sculpture and architectural art had attained.

Can there be anything more tragic than the

fact that the inheritors of this great cultural legacy, the descendents of the

ancient people of the Nilamata Purana who gave Kashmir its own creation myth,

are today facing a sinister threat of cultural extinction? Shaken by such a

horrifying prospect, a group of concerned members of the Kashmiri Pandit

community set up the NS Kashmiri Research Institute in Delhi on January 19, 1997

to launch a concerted drive to preserve, protect and project the heritage and

culture of the Kashmiri Pandits. It has been named after Prof. Nityanand Shastri,

one of Kashmir's most outstanding Sanskrit scholars who was a contemporary and

friend of great European Indologists like Sir Aurel Stein, Prof. J. Ph. Vogel,

George Grierson and Winternitz.

The Institute has chalked out a well

thought-out agenda and programme for achieving its objectives which had been

endorsed by the intellectuals of the community. This exhibition is an effort in

that direction, but it is only a curtain raiser, being the first in a series of

thematic exhibitions which the Institute proposes to organise in the near

future. On display are rare miniature paintings of the Kashmir school, Sharada

and Persian manuscripts, documents and books relating to Kashmiri Pandit

intellectual attainments and scholarship. Also on view are Kashmiri Pandit

costumes, artefacts and objects of ritualistic importance besides old

photographs showing social and religious customs of the Pandits.

'Unmeelan' is an attempt to capture the

real cultural face of Kashmir, battered and bruised, though it is today. A face

that has for long been kept away from view: I along with my colleagues in the

NSKRI hope that you will find the exhibition visually satisfying and

intellectually stimulating despite the many shortcomings that it obviously has.

Sharada Script

Named after "Sharada Desh", the

ancient name of Kashmir, the Sharada script developed from Brahmi, the mother of

all Indian scripts, around the 8th-9th century. Employed for writing Sanskrit,

and Kashmiri in ancient and medieval Kashmir, it is related to the Devanagari

script and is built along the same lines with the letters sa and ha coming at

the end of the alphabet. Aurel Stein has called it "the elder sister of

Devanagari."

Even after Persian was made the court

language of Kashmir, Sharada continued to be used for quite some time even by

Muslims. Several 15th and 16th century tombs in Kashmir have epitaphs written in

both the Perso-Arabic and Sharada scripts. Medieval saint Sheikh Makhdoom

Hamza's will preserved in the Srinagar Museum is written in Persian as well as

Sharada. The will was written in 1577.

Sharada alphabet soon spread to the

neighbouring Himalayan regions where it was widely used. Gurumukhi, the script

in which Punjabi is written, evolved from Sharada. However the use of Sharada

script is now limited to a very few members of priestly class of the Kashmiri

Pandits for writing horoscopes.

Revival of the Sharada script is a priorty

item on the NSKRI agenda.

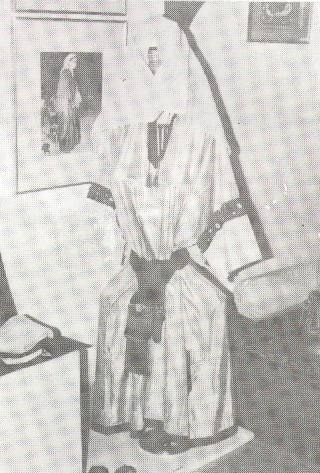

Kashmiri Pandit Costume

Literary and archaeological evidence shows

that in ancient and medieval times the costume of the Kashmiri male consisted

essentially of a lower garment, an upper garment and a turban. If Kashmiri

sculpture is any guide, men as well as women wore a long tunic and trousers,

probably due to Kushana influence. According to Hieun Tsang, they dressed

themselves in leather doublets and clothes of white linen. In winter, however

they covered their body with a warm cloak which the Nilamata Purana calls

Pravarana. The rich among them were also draped in fine woollen shawls while the

ordinary people had to rest content with cheaper woollen articles like the

coarse sthulkambala.

The use of different kinds of turbans

known as ushneek or shirahshata was widely prevalent. Strange though it may

seen, the dress of a woman in early Kashmir consisted mainly of sari and

tailored jackets or blouses. She is also shown wearing a long flowing tunic and

trousers. It was fashion for both men and women to braid their hair in different

styles, wearing sometimes tassels of varied colours.

It is, therefore, difficult to say how

long back in tradition does the present attire of Kashmiri Pandit males and

females go. Of course, in early Kashmir men and women both were fond of adorning

them selves with ornaments. They wore rings in the fingers, gold necklaces, ear

rings, armlets and wristlets and even amulets. The women also wore anklets,

bracelets, pearl-necklaces, pendants on the forehead and golden strings at the

end of the locks ( a forerunner of the attahor perhaps). One thing is certain,

the traditional dress of Kashmiri Pandits underwent a definite change after the

advent of Islam. Today the following articles compose their attire:

A. Pheran

The long flowing dress called the pheran-pravarna of the

Nilamata Purana is traditionally worn by both Pandit males and females. The

dress is always worn in a pair, the underlayer called potsh, being of light

white cotton. In case of women, the pheran has wide sleeves, overturned and

fringed with brocaded or embroidered stripes. Similar long stripes of red

borders are attached around the chest- open collars (quarterway down the front

of shoulders and all along the skirt. A loongy, or a coloured sash was tied

round the waist.

The traditional male garment is always

plain and has narrow sleeves and a leftside breast-open collar with a kind of

lapel or lace emerging from it.

B. Women's Headgear: Taranga

Taranga or the female headgear is reminiscent of the

racial fusion of the Aryans and Nagas to which the Nilamata Purana has referred.

It symbolizes the decorative hood of the crelestial serpent (nag) with a flowing

serpentine body tapering into a double tail almost reaching the heels of the

wearer. It is composed of the following parts:

Taranga - The elements for

composition of the Headgear:

a) Kalaposh - the cap, a conic

shape of decorative brocade or silken embroidery, attached with a wide and round

band of Pashmina in crimson, vermilion or scarlet. The conic shape would cover

the crown and the band would be shortened threefold around the forehead.

b) Zoojy - a delicate net-work

cloth topped by embroidery motifs, and worn over the crown of kalaposh and

tapering flowing down to the small of the back.

c) Taranga - it comprises of three

narrow and continuous wraps over and around the head, the final round having

moharlath, starched and glazed over with an agate-stone, crystal or a soft giant

shell.

d) Poots - the two long lengths of

fine white muslin hemmed together longitudanally with a "fish spine"

pattern. Lengthwise, then the whole piece is rolled and wrapped inwards from

both sides so as to form the long bodies of a pair of snakes with a pair of

tapering tails at the lower end and a hood at the other end (top) to open up and

cover the apex of the headgear while flowing down over the back almost touching

the heels.

C. Men's Headgear:

The turban is the traditonal headgear of the Kashmiri

Pandit males, though its use is very restricted now. This turban is not much

different from the turban the Muslims wear except that the Pandits do not wear

any scalp cap inside. The priest class among the Pandits would wear their

turbans in almost the Namdhari Sikh style.

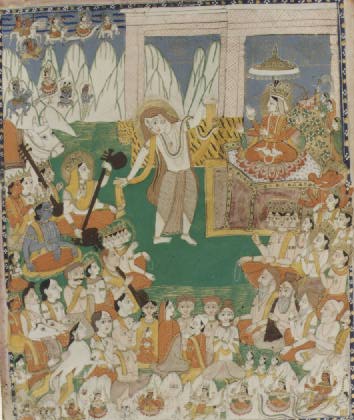

Kashmir school of miniature paintings

Shiva Dancing

It is for the first time in the history of

Indian, or world, art that miniature paintings of the Kashmir school are being

displayed in an exhibition. With the solitary exception of a recent work by a

Russian art historian, no attempt has been made so far for a systematic study of

this important school of art.

The story of art in Kashmir opens with a

pre-historic rock drawing discovered at the neolithic site of Burzahom depicting

a hunting scene. A subsequent stage of development is represented by

master-pieces of art in the shape of Harwan tiles and Ushkar (Wushkar) stucco

figures. The Nilamata Purana makes clear reference to the existence of painting

in ancient Kashmir. From 7th-8th century onwards the school of Kashmir art

acquired distinct features, even as it was absorbing Gandharan and Gupta

influences reaching its pinnacle of glory in the times of Lalitaditya. The

movement sustained till the 10th- 11th century when its fame spread throughout

the Himalayan region.

Although no direct example of Kashmir

painting of this period has survived, the characteristic features of the

Kashmiri style can be clearly seen in the Gilgit manuscript paintings assigned

to the 6th-7th century. The murals of the Buddhist monasteries of Alchi in

Ladakh, Mang Nang in Western Tibet and Spiti in Himachal Pradesh present a

successive stage of the development of the tradition of painting in Kashmir.

These mural paintings appear to be a pictorial translation of the exquisite

Kashmir bronzes dated to 9th to 11th century.

The Kashmiri artistic tradition faced

decay during the political and religious upheaval in the 14th century. Lack of

patronage and fear of religious persecution forced master painters of Kashmir to

neighbouring Himachal princedoms where the Kashmir style revived and flowered

after being grafted into the Pahari-Kangra school.

Despite large scale vandalism and

destruction in the subsequent centuries, the traditional artistic propensities

of the Kashmiris could not be entirely stiffed though. The Kashmir school of

miniature painting survived taking a new avtara during the late 18th century,

continuing through the l9th century to the early decades of the twentieth. The

Puja room (thokur kuth) of the Kashmiri Brahmins became a virtual museum of

religious art which found expression in the illuminations of Sharada

manuscripts, horoscopes, folk-art works like the krulapacch, nechipatra

(almanac) etc. besides individual paintings. The themes were essentially

religious with forms of Hindu deities and local gods and goddesses dominanting.

In fact miniature paintings became a

family tradition, passing from generation to generation. It even became a

collective act of creativity with one expert making the border, another

executing the drawing and a third one painting the colours. These Kashmir

miniature paintings are characterized by the delicacy of line introduced to the

massive and weighty proportions of form, the colour scheme being throughout

soothing, soft and harmonious. The facial type, in the words of Dr. A.K. Singh,

is "marked with ovaloid face, fleshy cheeks, double chin, acquiline nose

and full lips, highly arched eyebrows and almond shaped eyes". The division

of space has the unique charactristic of correlating the foreground and

background. Ornamental border, with occasionally strong use of gold, is another

striking feature of the school.

Unfortunately, this rich treasure of

miniature paintings has gone virtually unnoticed by art historians, making it

difficult to reconstruct a chronological history of the Kashmir school. 'Unmeelan'

is an attempt to invite the attention and appreciation of art lovers and

conneisseurs to this very important but neglected school of art.

Faces of Glory

Pandit Harabhatta Shastri

'The celebrated scholar of Shaiva lore'

Pandit Harabhatta Shastri

[ Pandit Harabhata Shastri (HBS) is a

name surrounded by a brilliant scholastic aura, though known to very small group

of Sanskrit scholars of Kashmir (a tribe that is diminishing day by day). And

even these few have nothing more than a sketchy information to give about the

life and works of the great Pandit. Sadder still, when we at NSKRI sought to

ascertain certain biographical details about him from some of his nearest

surviving kin, we almost drew a blank. The great man who wrote the most

brilliant gloss on 'Panchastavi' and brought out a series of Shaiva texts of

Kashmir, is virtually unknown to most Kashmiri Pandits today.

It was an American scholar, Prof. David

Brainered Spooner who came all the way from Harvard University to learn at the

feet of Sanskrit scholars of Kashmir like HBS. We are giving below a brief

biographical sketch of HBS who dazzled Dr. Spooner and came to be known as one

of the greatest interpreters of Shaiva philosophy of Kashmir. Yet we acknowledge

that a lot of light needs to be thrown on the celebrated scholar. Through these

columns we request Kashmiri researchers and scholars who may have had the good

fortune of coming into contact with HBS to provide us with more details about

his life and works. ]

Born as Harabhatta Zadoo in 1874 in a

family that has produced some of the top most Sanskrit scholars of Kashmir, HBS

had learning running in his veins. His father Pandit Keshav Bhatta Zadoo was the

Royal Astrologer in the Court of Maharaja Ranbir Singh, the then ruler of Jammu

and Kashmir who was a great patron of scholars and scholarship. His nephew, Prof

Jagaddhar Zadoo, has the credit of editing the first edition of the Nilmata

Purana with Prof Kanji Lal. The Zadoos originally belonged to Zadipur, a village

near Bijbehara in South Kashmir, but later migrated to Srinagar, their surname

being linked to the village of their origin thereafter.

As an atmosphere of Sanskrit learning

prevailed in the family, young Harabhatta took to it as fish take to water.

Studying Sanskrit at the Rajkiya Pathshala in Srinagar, it was in 1898, exactly

a century ago, that he obtained the degree of Shastri and came to be known as

Harabhatta Shastri.

In view of his profound scholarship, HBS

was appointed as Pandit, and later Head Pandit, at the Oriental Research

Department of Jammu and Kashmir state, a post from which he retired in 1931.

This was the Maharaja's own way of

patronising the learned men of his state.

His razor-sharp intellect, his great

erudition, and, especially his deep insight into the Shaiva philosophy of

Kashmir won him the esteem of such distinguished scholars as K. C. Pandey of

Lucknow University and Prof James H. Wood of the College of Oriental Languages

and Philosophy, Bombay. His repute attracted the well known linguist Prof Suniti

Kumar Chatterji to him and he stayed in Srinagar for two years to learn the

basics of the monistic philosophy of Kashmir Shaivism from him.

It was only after David B. Spooner came

from USA to Kashmir to learn from scholars like HBS and NS that Sanskrit began

to be taught as a subject at the Harvard University in 1905. At that time only

nine students were studying Sanskrit out of a total of 5000 at Harvard.

In the meantime HBS engaged himself in

scholarly pursuits which were to form the basis of his repute. He wrote his

famous commentaries on Sanskrit texts from Kashmir which included the 'Panchastavi'--

a pentad of hymns to Mother Goddess. With his profound scholastic background and

his deep insight into Shaiva and Shakta traditions, HBS explained and elucidated

Shakta concepts contained in the Panchastavi in his famous commentary, specially

on the 'Laghustava' and the 'Charastava' which came to be known as "Harabhatti"

after him. These hymns, held in high esteem from quite ancient times in Kashmir,

have a special significance for the votaries of Trika philosophy. There was a

debate for quite some time on the authorship of 'Panchastavi', some attributing

it to Shankaracharya, some to Kalidasa and some to Abhinavagupta. It was HBS who

proved it convincingly that it was actually composed by Dharmacharya. This view

was shared by Swami Lakshman Joo, too.

HBS also earned great repute for having

compiled and edited nine Shaiva texts, with notes and explanations, which were

published by the J & K Research and Publications Department under the

general title 'Kashmir Series of Texts and Studies.' Other significatnt works by

HBS include a commentary on 'Apadpramatri Siddhi' of Utpala, Vivarna on Bodha

Panchadashika and Parmarth Charcha.

This "celebrated scholar of Shaiva

lore", one of the greatest interpreters of the Shaiva philosophy of

Kashmir, passed away in 1951. His illustrious American disciple, Dr. Spooner,

often wrote leters to him and also to Prof Nityanand Shastri and Pandit

Madhusudan Shastri. The letters he wrote to HBS have been lost, but those he

wrote to NS have been preserved by NSKRI. In these letters he never forgot to

mention HBS and remember "the great days" he had spent with him.

NSKRI congratulates Moti Lal Kemmu for

winning Sangeet Natak Akademi Award

Noted Kashmiri dramatist, Moti Lal Kemmu

has bagged this year's Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for his outstanding

contribution to Kashmiri theatre. The award has come none too soon for the

celebrated playwright, for all through his dramatic career spanning over four

decades he has been constantly engaged in enriching Kashmiri drama and

strengthening the theatre movement in Kashmir in a maner no one else has. Kemmu

has already received the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1982 for his collection of

plays 'Natak Truchy'.

Born in 1933, Moti Lal Kemmu began his

career as a dramatist in the late fifties with the publication of 'Darpan

Antahpur Ka' -- an anthology of his three plays in Hindi. He created a stir in

the still and stagnant waters of Kashmiri drama when he published three of his

Kashmiri plays bristling with humour and satire, under the title 'Trinov' in

1966. Then came his full- length three-act play 'Lal Bo Drayas Lolare' which

dealt with women's struggle for freedom in the tradition-ridden male dominated

society. 'Tshay', an historical tragedy with existentialist overtones came next

in 1972. The Sahitya Academi Award winning 'Natak Truchy' was published in 1980

and 'Tota ta Aina ', a full length experimental play based on a folk-theme, in

1974.

In 1994, he published 'Yeli Dakh Tsalan',

a play about the response of Kashmiri folk-cultural tradition, with its roots

deeply embedded in human values, to the challenges posed by terrorism in

Kashmir. The play was translated by Dr. Shashi Shekhar Toshkhani into Hindi and

produced by the National School of Drama as 'Bhand Duhai' recently under .the

directorship of the well-known theatre personality M. K. Raina. The production

was a big draw with the theatre lovers of the capital, enthralling conneisseurs

as well as lay audiences.

Kemmu's plays are known for their candid

exposure of the absurdities and incongruities of life, using elements of the

Kashmiri folk style, "Bhand Pather" as well as modern absurd theatre

and Sanskrit drama with great effect. Besides being a playwright, he has also

directed several plays at a number of theatre workshops. Presently on a

fellowship from the HRD Ministry, he is engaged in writing a series of plays

based on Kashmir history, the first of which, 'Nagar Udasy' has come out a few

months back.

NSKRI congratulates Moti Lal Kemmu on his

achievement and wishes him many more years of creative activity in his chosen

field.

The Symbology of Shri Chakra

-- Dr C. L. Raina

In Upanishadic and Pauranic theology,

natural forces were divinized to help man understand the Immutable -- the primal

source of creation, preservation and dissolution of the universe. This provided

a psychic opening for a vision of the unity of man, god and universe. The Vedic

gods are cosmological in character and represent man's aspiration to be in tune

with the divine. Agni, Vayu, Ashvinis, Surya, Mita, Varuna, Shri, Prithvi etc of

the ancient Vedic texts are gods who represent various moods and modes of nature

and play definite roles in the cosmic drama to keep the rhythm of the universe

vibrant. And it is this rythm that is represented by mandals and chakras

referred to as 'zageshwar' in Kashmiri religious terminology.

Seers attributed names and forms to these

cosmic forces, and gave them specific traits as aspects of divinity through

concepts. They visualized them through the concepts of bindu or the dot, trikona

or the triangle, vritta or the circle, bhupura or the doorway, linga-yoni or the

procreative symbols representing Shiva-Shakti. The different devtas and devis,

male and female deities, were allotted their vahanas or the vehicles in the form

of animals and birds giving definite meanings to their symbology.

Thus Surya, the sun god, has his celestial

chariot drawn by seven horses, each horse symbolising a definite ray. In the

same manner dwadasha adityas are symbolic of the twelve months of the year. 'Aditya'

means the son of Aditi -- the universal energy. She represents the prakriti

aspect or the 'nature mother', while akash is termed as the 'father sky'. The

surya mandal drawn and worshipped by Kashmiri Pandit ladies on Ashadha Shukla

Saptami reminds of the hoary past when the Vedic deity was worshipped in the

compounds and kitchens in Kashmiri homes and offerings of rice were placed on

the mandal or the circular drawing representing it.

The Sapta Rishis: Vashistha, Kashyapa,

Atri, Jamadagni, Gautama, Vishwamitra and Bhardwaja too are symbolic, each

representing the cosmic principle in one or other form. While Kashyapa, the

progenitor, represents temporal existence, Bhardwaja symbolises Jamadagni

symbolises lustre and Kundalini symbolises the vital breath.

Shri Chakra is the most sacred symbol in

the Kashmiri Shakta tradition. The mool trikona or the central triangle of the

diagram is the yoni with lajjabija and hrim its symbol. The triangle is

equilateral and its point of concurrence is bindu -- the absolute reality

without any dimension. Its symbolic meaning is made explicit in the following

shloka:

Shri Chakra priya bindu tarpana para Shri

Rajrajeshwari

Shri Chakra is the priya bindu is the

eternally pleasing Shiva absorbing in it Shri Rajrajeshwari, the supreme

sovereign mother creatrix who is tarpana para as transcendental in pleasing

native. Bindu represents the dot of our conciousness which gets materialised

through saguna-sadhana of Shri Sharika manifest in the Chakreshwara. The lines

of this are the 'wave beats' of the divine and every triangle, lotus petal and

circle is the abode of varnamala (the alphabet) or matrikas. Matrikas are

worshipped at the time of jatakarma, devaguna and Shakta rituals related to

homas of Shri Jwala, Sharika, Rajnya, Bala, Bhadrakali and Tripura Sundari.

Shri Chakra is a diagram signifying hope

and aspiration. According to those who practice Shakti puja, Shri Chakra

symbolises the "One by whom all devatas live." Infinite rays of light

emanating from the chakra are received by devotees who worship it with the kadi

mantra of fifteen syllables where the 'bindu' represents the immortal face of

Shri Sharika -- the Mother of all bija mantras.

A sound is heard. Timelessness is

experienced. The spirit feels the pulsation of the Divine Mother's presence.

Kashmiri Pandits used to worship the Shri

Chakra on meru made of crystal in their thakurdwaras or puja rooms which would

be situated generally in the madhya koshtha or the second storey of their homes

in accordance with vastukala and Shakti Siddhanta or the principles of Shakti

worship. Some used to worship it on a properly engraved copper plate and some on

bhoj patra or the birch-bark leaf.

Worshipping Shri Chakra is an essential

religious practice of the Kashmiri Pandits.

|