The Poplar and the

Chinar: Kashmir in a Historical Outline

by Subhash Kak

Louisiana State University Baton

Rouge, LA 70803-5901

Published in International Journal of Indian

Studies, vol 3, 1993, pp. 33-61

| The

paper presents the recent militancy in Kashmir in a historical context.

The policies of the Government of India that have contributed to the

alienation of the different religious communities of the State are

analyzed. The militancy is seen as an attempt by the fundamentalists to

wean the Kashmiri Muslims away from their heritage of Rishi Islam that

includes elements of Shaivism.

Keywords

: Kashmir, Indian politics, quotas, Islamic militancy, terrorism. |

Insurgency and Terror

The

middle of 1989 saw the beginning of a campaign of terror  against the Kashmiri

minorities by Muslim fundamentalists and an insurgency against the Indian

government. Within a year hundreds of selective and random murders forced nearly

all the Kashmiri Hindus and Sikhs, who comprise less than 10 percent of the

population of the Vale, to leave their homes for refuge in the Jammu province

and in Delhi.

against the Kashmiri

minorities by Muslim fundamentalists and an insurgency against the Indian

government. Within a year hundreds of selective and random murders forced nearly

all the Kashmiri Hindus and Sikhs, who comprise less than 10 percent of the

population of the Vale, to leave their homes for refuge in the Jammu province

and in Delhi.

The Jammu and Kashmir State is a union of different

ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups. There are groups in the

Muslim-dominated Kashmir who have sought independence or a union with Pakistan.

The terror then represents a plan to eliminate minorities that may not wish to

break Kashmir's ties with India.

There are several Muslim groups at work now with their

own agendas. Not all of them espouse violence and neither are all focused on

political aims. It would be wrong, therefore, to call the events in Kashmir as a

struggle for freedom. As in a play of shadows across a silk curtain,

understanding the recent events of Kashmir requires a broad knowledge of the

plot and considerable imagination. The main actors in this drama are the

governments of India and Pakistan and the various Muslim factions in the valley

of Kashmir. The roles of the Indian and the Pakistani governments are relatively

clear. The Indian government claims the territory of the State under the control

of Pakistan, but Nehru and his successor governments have let it be known that

it would be willing to accept the actual line of control as the international

border. Pakistan covets the Vale of Kashmir since it has a Muslim majority, and

Pakistan was shaped out of India in 1947 from the Muslim majority regions. The

Muslim leadership of the Kashmir valley has in the past four decades insisted on

a certain isolation from the rest of the Indian Union. This policy has been made

a shibboleth by many Indian national, left-wing parties for a belief in

secularism.

India and Pakistan have fought four wars for the

control of the valley. In the first war, during 1947-8, the fighting was

confined to the State. The second war in 1965 became a general conflict. The

third war in 1971 began over the revolt in the eastern wing of Pakistan but

eventually engulfed Kashmir. The most recent war has been fought by proxy

through agents by Pakistan in Kashmir. It started in 1989 and is still

continuing.

No systematic studies of Kashmiri Islam have been

carried out. But its situation is very similar to that of Indonesian Islam, and

one might use the analysis of Clifford Geertz (1960) and successors (Hefner

1985, Kipp and Rodgers 1987) to understand its dynamics. We then have the

classification of orthodox , traditional , and karkun (urban, State employees)

to parallel the labels of santri, abangan, priyayi for Javanese Islam. The

interesting aspect of this classification is the fact that the karkun (or the

priyayi in Java) has an ethos outside the main religious framework. In Java the

priyayi are Muslims who hold on secretly to the Hindu-Buddhist values, whereas

in Kashmir the karkun have generally been the Hindus of the valley. In other

words, if the orthodox are the sayyids and the mullahs , the traditional the

peasants and the craftsmen, then the karkun are the administrators, or the

secular gentry. This classification is naturally a great simplification, but it

provides important insights.

Recent Kashmiri history can be examined in terms of the

dynamics between these three groups. So long as Kashmir was isolated, the three

groups lived in a certain harmony amongst themselves. But from time to time

forces from within and outside have threatened this equilibrium. The prosperity

of the past four decades and modernization have spread the karkun and secular

ideals within the Islamic community. The orthodox group has felt challenged by

this phenomenon. This has stoked the fires within Kashmiri Islam of the

long-standing struggle between the champions of the orthodox variety of

doctrinaire Islam and the vast majority of adherents who subscribe to a popular

religion that is heavily based on the native pre-Islamic traditions. The groups

spearheading the current movement in Kashmir seek to steer the population away

from its Hindu roots.

This struggle for the heart and soul of the Kashmiri

Muslim against the insidious and growing karkun culture explains the fury and

intensity of the militants. The orthodox have sought a revolution that has shown

no mercy. So if the insurgency has been against the Indian government and the

Kashmiri Hindus, it has also been directed against the dominant religious

tradition of the Kashmiri Muslims themselves.

The State of Jammu and Kashmir and the Enchanted Vale

Before the partition of the State at the end of the 1947-9

war between India and Pakistan, it consisted of the Vale of Kashmir, the

province of Jammu, the districts of Ladakh and Baltistan, and the Gilgit agency.

The inhabitants of the Gilgit region and the Kashmir valley speak languages that

are classed as belonging to the Dardic family of the Indo-Aryan language family;

in Jammu Dogri, of the Indo-Aryan family, predominates; and in Ladakh and

Baltistan the language is a variant of Tibetan. From the point of view of

religion also the State presents a mosaic. Gilgit, Kashmir, and Baltistan are

predominantly Muslim; Jammu is likewise Hindu, and Ladakh is Buddhist. A little

over half of the population of the State is concentrated in the Vale of Kashmir

which accounts for only 10 percent of the area, and Ladakh, Gilgit, and

Baltistan are very sparsely populated. The State has some of the most

breathtaking scenery in the world. The Vale itself is about 84 miles long with a

breadth of 20 to 25 miles and a mean altitude of 5,600 feet above sea level

(Drew 1875, Younghusband 1909). It is famed for its beauty of lakes and mountain

streams, chinars and poplars, irises and roses. The Vale is also famed for a

great tradition of scholarship, music and arts, shawls and carpets (Singh 1983).

Of the different regions of the State, we know the

history of the Vale the best. This is due to the 12th century Ra jatarangini of

the historian Kalhana. Buddhism was introduced into the Vale by the missionaries

of the emperor Ashoka (269-232 B.C.). The Kushan emperor Kanishka (c. 100 A.D.)

convened a Buddhist council in Kashmir which led to the foundation of Mahayana

Buddhism. Kashmiri missionaries played a leading role in the spread of Buddhism

into Central Asia and China.

The Karkota dynasty of the seventh and eighth centuries

provides us with the first authentic accounts of the government in the Vale.

Lalitaditya (724-61) was the outstanding king of this dynasty. Lalitaditya built

the famed Sun temple of Martand. In the 9th century Avantivarman built a grand

capital south of Srinagar whose ruins can still be seen. These centuries also

saw a flowering of Sanskrit learning and philosophy in Kashmir.

The rise of the Turko-Mongols under Chingiz Khan and

his successors brought considerable turmoil to Central Asia after the 12th

century. This disorder spilled into the Vale. Powerful feudal lords vied for

power and many adventurers from outside invaded.

The end of the Hindu rule was part of a fascinating

drama of intrigue and treachery. In 1320 Rinchana, a Tibetan prince, usurped the

throne and sought to be converted to Hinduism. Upon the refusal of the Brahmins

to do so he embraced Islam. After his death in 1323, his Hindu queen Kota Rani

ruled until 1338 although the nominal king was her new husband Udayana, who was

the younger brother of Suhadeva, the king before Rinchana. On Udayana's death

Kota Rani ruled by herself for a few months until the power was seized by Shah

Mir, a native of Swat, who now established the first Muslim dynasty in the Vale.

Islam spread quickly in Kashmir. It appears that there

were periods of persecution of Hindus and their forcible conversion that

interspersed longer periods of living in harmony. The first such episode of

forcible conversion was during the reign of Sikandar (1389-1413) when, according

to tradition, the persecution was so severe that the Hindus either left the

valley or converted to Islam until only eleven Hindu families remained. But

Sikandar's son Zain-ul-Abidin (1420-1470), popularly known as Badshah or Great

King, was an enlightened ruler whose policy of religious tolerance persuaded

many Hindus to return to the Vale. But after Zain-ul-Abidin the pressure on

Hindus to convert to Islam continued. According to a tradition 24,000 Brahmin

families were forced to convert during the stay in the valley of Mir Shams-ud-din

Iraqi, who arrived in 1492 to proselytize on behalf of the Sufi order of

Naqshabandis (Sender 1988).

The Vale was made a part of the Mughal empire by Akbar

in 1587. It soon became a favourite summer resort for the Mughal rulers who

built many gardens here. The Mughal administration was fair and it brought much

prosperity. But as the Mughal empire weakened the governors assumed more power

and some of them reintroduced religious repression. In 1752, with the collapse

of the Mughal power, Kashmir came into the control of the Afghans. This rule was

perhaps the most tyrannical in the history of the land. The Sikhs, under Ranjit

Singh, wrested Kashmir from the Afghans in 1819. In 1846, following the defeat

of the Sikhs by the British, Gulab Singh, the Dogra ruler of Jammu purchased the

Vale from the British.

The Dogras appear to have maintained large degree of

autonomy during the period of Muslim rule in India. The Sikh kingdom of Lahore

recognized Jammu to be a protected state. In 1834, Gulab Singh conquered the

independent state of Ladakh. Baltistan, to the west of Ladakh, was defeated in

1840. In 1841 he attempted to expand into Western Tibet but this campaign ended

in disaster. The Gilgit region was also inherited by the Dogras from the earlier

Sikh kingdom. Thus by the mid-nineteenth century the state of Jammu and Kashmir

had assumed its pre-partition form with the Dogra king as its ruler.

In the 1845 war between the British and the Sikhs,

Gulab Singh, although a feudatory of the Sikhs, had not taken sides. The British

recognized him as the independent ruler of Jammu, Poonch, Ladakh, and Baltistan

in a treaty signed in 1846. But when Gulab Singh purchased the Vale of Kashmir,

he accepted British paramountcy which meant the British right to control his

foreign relations.

The movement for independence in British India spilled

over to Kashmir as well. In the 1920's there were demands for redress of

grievances. There was further unrest in the 1930's which prompted the Maharaja

to take stern measures. However, the disturbances continued and eventually the

Maharaja accepted the establishment of a legislative assembly. Sheikh Abdullah

emerged as the most prominent leader of this movement that led to this major

reform.

The Maharaja appeared to hold out for independence in

August 1947 when India was partitioned. But in late October of that year

Pakistani tribesmen, led by military officers in civilian clothes, tried to take

the Vale by force. But instead of quickly seizing Srinagar, as they were in

position to do, they stopped to plunder, murder, and rape. The Maharaja's hand

was now forced and he acceded to the Indian Union and asked for help to expel

the invaders. Sheikh Abdullah, who had been released from prison, endorsed this

decision. Soldiers of the Indian Army were now flown into Srinagar and this

turned the tide of the invasion. Pakistani regulars were now sent in and the war

raged throughout 1948. Finally, under the supervision of the United Nations a

cease fire was declared on 1 January 1949. Pakistan occupied 33000 square miles

of the 86,500 square miles of Jammu and Kashmir State. India held the Vale of

Kashmir and most of Jammu province and Ladakh, whereas Pakistan controlled parts

of Jammu and Kashmir provinces, Baltistan, and the Gilgit region.

Shaivistic and Bhakti Roots of Kashmiri Religion

To understand the religious divide in the Vale it is

necessary to go back to the Shaivite roots of the popular religion. It is

important to note that this tradition fits squarely within the greater Indian

tradition. The Rigveda presents a monistic view of the universe where an

understanding of the nature of consciousness holds the key to the understanding

of the world. This is further emphasized in the Upanishads, the six

philosophical schools, Buddhist and Jain philosophy, the Shaivite and the

Tantric systems. Of course this emphasis varies. And sometimes seemingly

different terms represent the same central idea. For example the s unyata (void)

of Madhyamika Buddhism and the brahman (universe) of the Upanishads are forms of

the monistic absolutes. Two opposite metaphors thus represent the same central

idea. Likewise the dualism of Sa m khya and of the Jains is correctly seen as

projection of a monistic system of universal consciousness that manifests itself

in the categories of the physical world and sentience. A grand exposition of the

system, that explains how different perspective fit in the framework, is

contained in the Bhagavad Gi ta . Even the Iranian religion of Zarathushtra may

be seen as reformulation of the earlier Vedic tradition (Boyce 1975) in the same

sense that Vaishnavism is.

Kashmir Shaivism, reached its culmination in the

philosophy of Abhinavagupta and Kshemaraja (tenth to eleventh century AD) (Chatterji

1914, Dyczkowski 1987, Gnoli 1968, Kaw 1969, Pandey 1963, Jaideva Singh 1977,

1979, & 1989). Their trika (three-fold) school argued that reality is

represented by three categories: transcendental ( para ), material ( apara ),

and a combination of these two ( para para ) (Lakshman Jee 1988). This

three-fold division is sometimes represented in terms of the principles s iva, s

akti, an u or pati, pa s a, pas u . S iva represents the principle behind

consciousness, s akti its energy, and an u the material world. At the level of

living beings pas u is the individual who acts according to his conditioning,

almost like an animal, pa s a are the bonds that tie him to his behaviour, and

pati or pas upati (Lord of the Flock) is s iva personified whose knowledge

liberates the pas u and makes it possible for him to reach his potential. The

mind is viewed as a hierarchical (krama) collection of agents ( kula ) that

perceives its true self spontaneously ( pratyabhijna ) with a creative power

that may be viewed as being pulsating (spanda) . This last attribute recalls the

spenta of the Zarathushtrian religion, where this word represents the power of

creation of Ahura Mazda . Thus Kashmir Shaivism appears to have attempted a

reconciliation of the Iranian religion with its Vedic parent.

The Pratyabhijn a (recognition) system is named after

the book Stanzas on the Recognition of Ishvara or Shiva which was written by

Utpala (c 900-950). It appears Utpala was developing the ideas introduced by his

teacher Somananda who had written the earlier Vision of Shiva . In Shaivism in

general, Shiva is the name for the absolute or transcendental consciousness.

Ordinary consciousness is bound by cognitive categories related to conditioned

behavior. By exploring the true springwells of ordinary consciousness one comes

to recognize its universal (Shiva). This brings the further recognition that one

is not a slave (pasu) of creation but its master (pati) . In other words, an

intuition of the true nature of one's consciousness provides a perspective that

is liberating.

For the spanda system the usual starting point is the

Aphorisms of Shiva due to Vasugupta (c 800). His disciple Kallata is generally

credited with the Stanzas on Pulsation . According to this school the universal

consciousness pulsates of vibrates and this ebb and flow can be experienced by

the person who has recognized his true self.

Abhinavagupta wrote a profound commentary on Utpala's

Stanzas on Recognition. Shaivite philosophy may be said to have reached its full

flowering with his philosophy. Abhinava also wrote more than sixty other works

on tantra, poetics, dramaturgy, and philosophy. His disciple Kshemaraja also

wrote influential works that dealt with the doctrines of both the schools of

Recognition and Pulsation. Abhinava emphasized the fact that all human

creativity reveals aspects of the seed consciousness. This explains his own

interest in drama, poetry, and aesthetics.

According to the ancient doctrine of Sa m khya physical

reality may be represented in terms of twenty-five categories. These categories

relate to an everyday classification of reality where prakrti may be likened to

matter, and purusa to mind. Kashmir Shaivism adds eleven new categories to this

list. These categories characterize different aspects of consciousness.

Any focus of consciousness must first be circumscribed

by coordinates of time and space. Next, it is essential to select a process (out

of the many defined) for attention. The aspect of consciousness that makes one

have a feeling of inclusiveness with this process followed later by a sense of

alienation is called maya . Thus maya permits one, by a process of

identification and detachment, to obtain limited knowledge and to be creative.

How does consciousness ebb and flow between an identity

of self an an identity with the processes of the universe? According to Shaivism,

a higher category permits comprehension of oneness and separation with equal

clarity. Another allows a visualization of the ideal universe. This permits one

to move beyond mere comprehension into a will to act. The final two categories

deal with pure consciousness by itself and the potential energy that leads to

continuing transformation. Pure awareness is not to be understood as similar to

everyday awareness of humans but rather as the underlying schema that the laws

of nature express.

Shaiva psychology is optimistic, scientific, secular,

and liberating. At the personal level it emphasizes reaching for the springwell

of creativity ( sakti ) and the schema underlying this creativity ( siva ). The

journey leading to this knowledge may be begun in a variety of ways: through

sciences, the arts, and creative social activities. But this exploration of the

outside world is to be taken as a means of uncovering the architecture of the

inner world. Shaiva psychology also reveals that the notion of bhakti, which has

played a central role in the shaping of the Indian mind during the past

millennium, may be given a focus related to a quest for knowledge.

The intellectual theories of Kashmir Shaivism were

given popular expression by the great mystic Lalleshvari or Lalla (1335-1376).

Her sayings, vakya , form the basis of much of the Kashmiri world-view that

emerged later. But from Lalla onwards the emphasis did shift to the devotional

aspects of Kashmir Shaivism (Temple 1924, Odin 1994). The notion of recognition

of one's true self was exalted to the central role in the popular religion

including Kashmiri popular Islam that views her va kyas and the sayings of her

disciple Sheikh Nur-ud-din (1377-1438), Nanda Rishi , as sources of spiritual

wisdom. Two of Lalla's va kya that have been adapted from Bamzai (1962) are

given below:

1)

I saw myself in all things

I saw God shining in everything.

You have heard, stop! see Shiva

The house is his, who am I Lalla.

2)

Shiva pervades the world

Hindu and Muslim are the same.

If you are wise know yourself

Then you will know God.

"Lalla is as much a part of Kashmiri language,

literature, and culture as Shakespeare is of English" is the assessment

of Kachru (1981). Says her own pupil Nanda Rishi:

That Lalla of Padma npor-she drank

Her fill of divine nectar;

She was indeed an avata r of ours.

O God, grant me the self-same boon!

(Kaul 1973)

Nur-ud-din was followed by a large number of Rishis

from both the Hindu and the Muslim communities. The Islamic Rishis provided

the leadership to the popular religion of the Kashmiri Muslims.

By the end of the nineteenth century the Kashmiri

Hindus were about seven percent of the population of the Vale. Within the

community itself a two-fold division had taken place by this time. Those who

specialized in the secular sphere, studied Persian and undertook

administrative employment, became known as the karkuns ; others who did

priestly duties requiring knowledge of Sanskrit were termed bhasha bhatta

(Sender 1988, Madan 1989). In recent years this sub-division is disappearing

and karkun values have become the dominant ethos of the community.

Islam in Kashmir

The core of Islam rests on the Koran and narratives

about the Prophet's life contained in the Hadith. In the next layer is the

sharia ---Islamic law. The ulama , who are the theologians who are occupied

with the interpretation of the Koran and the Hadith, are the heart and soul

of Muslim orthodoxy. The multiple interpretations of the Koran and the

Hadith finally formalized into four orthodox schools by 10th century A.D.

when the gates of itjihad (individual interpretation of the Koran and the

Hadith) closed shut. No further extensions of the Law are now permitted. The

body of orthodox Islam is called Sunnite Islam after the Arabic sunna ,

custom.

The challenge to the orthodox Islamic law by the

pre-Islamic pantheistic traditions of Arabia and Iran crystallized within

the Islamic framework through the mystical tradition of Sufism. The Sufi

teachers from Central Asia and Iran had a hand in converting Kashmiris. The

Rishi tradition of Kashmir went hand in hand with the Sufi tradition.

Islam in the Indian sub-continent has incorporated

many impulses that hearken back to the original Hindu roots of the

inhabitants (Mujeeb 1967, Ahmad 1969). In the Vale of Kashmir the practice

of Islam centres around worship at the many shrines scattered across the

region. At many of these shrines relics of Pirs and Rishis are worshipped.

In the beginning Islam represented the separate

identity of the immigrant from Dardistan, Central Asia, or Iran. As it

gained converts the difference in the Hindu and Islamic religious identities

in the countryside was perhaps not marked. In the late 14th century many

Sayyid refugees arrived from the West and they started agitating for

enforcement of the Koranic law. But the popular religion took its

inspiration from the Sufis and the Rishis that followed Nur-ud-din.

Some of Nanda Rishi's sayings are given below:

1)

The dog is barking in the compound

O brothers, give ear and listen:

As one sowed, so did he reap;

You, Nanda, sow, sow, sow.

2)

Your face washed, you call believers to prayer

How can I know, O Rishi, what are your feelings,

what are your prostrations for

You have lived a life without seeing (God)

Tell me to whom you offer prayers.

If you listen to truth, you will master the five

(senses).

If you make union with Shiva

Then only, O Rishi Mali, will prayer avail you.

[Adapted from Bamzai 1962]

Many Rishis followed Nanda Rishi and they helped

define the uniqueness of Kashmiri Islam. Not all Rishis used Sanskritic

concepts to describe their experience. With time Persian concepts and

stylistic devices were increasingly used. Eventually the Sufis of Kashmir

were also permeated greatly by the Rishi ideals. Writing in 1542 Mirza

Haider says in his Tarikh-i-Rashidi : "The Sufis have legitimized so

many heresies they know nothing of what is lawful... They are forever

interpreting dreams, displaying miracles and obtaining from the unseen

information regarding either the future or the past. Nowhere else is such a

band of heretics to be found... (they) consider the Holy Law ( shariat )

second in importance to the True Way ( tariqat , tradition) and that, in

consequence, the people of the Way have nothing to do with the Holy

Law." (quoted in Sufi 1947-8, pages 19-20)

Writing about a hundred years ago, Lawrence

ascribed the delightful tolerance between Hinduism and Islam to

"chiefly the fact that the Kashmiri Musalmans never really gave up the

Hindu religion." He added: "I do not base my ideas as to the

laxness of Kashmiris in religious duties merely on my own observations. Holy

men of Arabia have spoken to me with contempt of the feeble flame of Islam

which burns in Kashmir and the local mullas talk with indignation of the

apathy of the people." (Lawrence 1895)

The amity between the Muslims and the Hindus has

continued until this recent crisis. The vast majority of the Muslims

continue to follow the religion of the Islamic Rishis. According to the

Kashmiri Muslim historian G.M.D. Sufi:

A number of the practices of the Kashmiri Musalman

are (un-)Islamic... The Buddhist worship of relics has insidiously crept

into India's Islam. It is nowhere so prominent as in Kashmir. Hazratbal is

an outstanding example. On the occasion of the exhibition of the Prophet's

hair ... crowds of Kashmiris are seen weeping and wailing like the Jews

before the Wailing Wall... The Pirs have almost created a priesthood and

hereditary sacred caste. Necromancy and a belief in omens and magic has

gained ground in spite of the (Koranic prohibition against them)... Pure

monotheism and the moral fervour of a society based on social equality has

in practice nowhere receded more into the background. The ringing of a bell

precedes the call to prayer in several mosques in the Valley today... The

Kashmiri Muslim has transferred reverence from Hindu stones to Muslim

relics. (Sufi 1947-8, p. 688)

Many of the shrines of popular Islam are the

ancient Hindu-Buddhist shrines, the Jami' Masjid of Srinagar being an

important example (Sufi 1947-8, p. 512). According to M.A. Stein this is

perhaps true even of the most popular Islamic shrine at Hazratbal (Stein

1979).

Kashmiri Culture and Literature

To understand the Kashmiri mind it is best to consider

its poets. For the popular culture, which is permeated with the mystical

tradition, one must again begin with Lalla. Lalla describes her own

spiritual awakening thus:

1)

I, Lalla, filled with love

Searched day and night

In my own house I found the wise one

Whom I beheld at the moment

Which was the most auspicious of my life.

2)

Slowly I stopped my breath

The lamp lit and I realized my true identity

In the dark recesses of my soul

I held fast to the inner light

And emitted it outwards.

[Lalla translated by Odin 1994] |

|

The major poets who followed Lalla include Habba

Khatun (c 16th century), Rupa Bhavani (1621-1721), Arnimal (d. 1800), Mahmud

Gami (1765-1855), Rasul Mir (d. 1870), Parmanand (1791-1864), Ghulam Ahmad

Mahjur (1885-1952), Abdul Ahad Azad (1903-1948) and Zinda Kaul (1884-1965).

Habba Khatun is credited with originating the lol style of poetry where the

predominant mood is that of longing and romantic love. Arnimal also wrote in

the lol style. Rupa Bhavani, Mahmud Gami, Rasul Mir, Parmanand continued in

the mystical tradition of Lalla and Nanda Rishi. Mysticism and romantic love

are the two main strands in the tapestry of the Kashmiri psyche. Often the

two strands get intertwined since romantic love can be a metaphor for a

spiritual emotion.

1)

Which rival of mine has lured you away from me?

Why are you cross with me?

Forget the anger and the sulkiness,

You are my only love,

Why are you cross with me? [ Habba Khatun

translated by Kachru (1981)]

2)

Oh, spinning-wheel!

Do not grain

For I shall apply fragrant oil to your straw

rings.

And, you, Hyacinth!

Raise your head from under the earth for

Narcissus is waiting with cups of wine,

The jasmine will fade and will not bloom again.

Do not groan

Oh, my spinning-wheel! [ Arnimal translated by

Kachru (1981)]

3)

Seeking to know man

I asked the bubble:

How live you on water?

I asked of the butcher about love

Said he: Steel your heart with love

This kababs taste better when overdone.

How live you on water?

The breath of the lover blew a bubble

Another breath and it joined water again.

Who died? what's alive is the riddle.

How live you on water? [ Mahmud Gami ]

Mahjur, Azad, and Zinda Kaul and their successors have

tried to forge a new sensibility in some of their poems but the mystical and

the lol continue to be the dominant ethos.

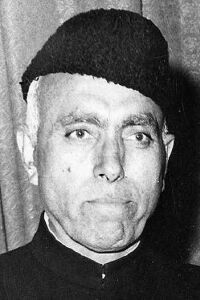

Sheikh Abdullah and the National Conference

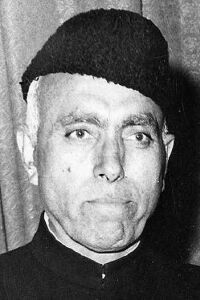

Sheikh Abdullah (1905-1982), the towering Kashmiri

politician of the past half century, was a powerful advocate of the Kashmiri

Muslims. His political career was launched when he galvanized his people to

agitate for reforms in 1931 during the rule of Hari Singh (Kaul 1985). Next

year a political party, Muslim Conference, was formed with Abdullah as its

first president. Under pressure from the British the Maharaja set up a

Commission to study constitutional reforms in the State. The recommendations

of this Commission led to the establishment of a legislative assembly of

seventy five members, thirty three of whom would be elected on a communal

basis, and an extremely limited franchise. When first convened in 1934, 19

of the 21 seats allotted to the Muslims were won by the Muslim Conference.

century, was a powerful advocate of the Kashmiri

Muslims. His political career was launched when he galvanized his people to

agitate for reforms in 1931 during the rule of Hari Singh (Kaul 1985). Next

year a political party, Muslim Conference, was formed with Abdullah as its

first president. Under pressure from the British the Maharaja set up a

Commission to study constitutional reforms in the State. The recommendations

of this Commission led to the establishment of a legislative assembly of

seventy five members, thirty three of whom would be elected on a communal

basis, and an extremely limited franchise. When first convened in 1934, 19

of the 21 seats allotted to the Muslims were won by the Muslim Conference.

Sheikh Abdullah was much influenced by the leaders

of the Indian National Congress, in particular Jawaharlal Nehru, whom he

first met in 1937. He had already worked closely with the Kashmiri socialist

Prem Nath Bazaz. Having by now recognized that popular Islam represented his

natural constituency he decided to enlarge the scope of his political party.

He stated his goal of forming a wide-based political movement in a speech in

1938:

We must end communalism by ceasing to think in

terms of Muslims and non-Muslims when discussing our political problems...

We must open our doors to all such Hindus and Sikhs, who like ourselves

believe in the freedom of their country from the shackles of an

irresponsible rule. (Bamzai 1962, p. 664)

Sheikh Abdullah clearly repudiated the sectarian

policies of M.A. Jinnah and the Muslim League. In 1939 the name of Muslim

Conference was changed to National Conference to emphasize its secular

character. The orthodox Muslims did not forgive Abdullah for this and they

remained forever opposed to him.

Sheikh Abdullah walked a tightrope to satisfy the

many different groups. His speeches in mosques used religious imagery to

appeal to the orthodox Muslims and disarm the influence of their leaders who

challenged him. But his real hard-core support lay amongst the Kashmiris who

professed the popular variety of the Islamic religion. His closeness to the

leaders of the Congress Party and his emphasis on secularism led to the

revival of the Muslim Conference by Ghulam Abbas. This revival also

reflected the divide between the Kashmiri and non-Kashmiri Muslims of the

State. Ghulam Abbas came from the Jammu province where the language is

closely related to Punjabi. Muslims of Jammu saw a convergence of their

interests with those of the Muslims of Punjab. On the other hand, Sheikh

Abdullah was endeavouring to define a special position for the Kashmiri

Muslims.

Muslim League represented the aspirations of the

orthodox Islamic minority of the mullahs, the Islamic intellectuals, and the

descendents of the immigrants from Central Asia and Iran. These groups felt

that unless their apartness was given a legal basis they might not be able

to preserve their heritage as a minority in a democratic India with its

Hindu majority (Embree 1989, Gilmartin 1988, Jalal 1990, Kak 1991, Shaikh

1989). Since Kashmiri Islam is so radically different from orthodox Islam,

the philosophy of Muslim League could never have mass appeal in Kashmir.

Sheikh Abdullah worked hard in the interests of the Kashmiri Islamic

community in the emerging political frameworks of Pakistan and India. He

appears to have calculated that Pakistan would eventually either imply

orthodox Islam or Punjabi cultural domination.

Partition and the War of 1947-8

At the time of the partition of India in 1947, only

the Muslim Conference, which was based mainly in Jammu, was in favour of the

State's accession to Pakistan. On the other hand Hindu Sabha in Jammu and

the Maharaja were hoping that the State could become independent. There were

other groups in Jammu who wanted accession to India, whereas Sheikh Abdullah

and his National Conference also appeared to be working for independence but

given a choice between accession to Pakistan or India they felt that they

could preserve autonomy for Kashmir within the secular Indian Union. The

attack by the Pakistani tribesmen forced the hand of the Maharaja. As the

tribesmen reached the outskirts of Srinagar, the Maharaja sought the aid of

the Indian army. He was advised that this could not be done unless the State

acceded to the Indian Union. Sheikh Abdullah accompanied the Maharaja's

Minister to Delhi to communicate to the Indian government acceptance by the

Maharaja of all Indian conditions. On 26 October 1947 the Maharaja signed

the Instrument of Accession.

Indian troops were flown in to protect Srinagar on

October 27. Soon the tribesmen and the Pakistani soldiers were in retreat.

By November 14 most of the Vale was in the control of the Indian army. By

winter the fighting had reached a stalemate and on 31 December 1947 Nehru

referred the Kashmir dispute to the United Nations.

In 1948 the war continued at other fronts. Pakistan

tried to cut off Ladakh from Kashmir but it was unable to do so. In the

autumn of 1948 the Indian army captured Poonch in the Jammu province. The

Indian army now threatened to cut the Pakistan controlled area in two by

reaching the international border beyond Poonch. Pakistan now wished to

enlarge the conflict by attacking Jammu so that the State would be cut off

from India. There was great pressure on both countries to stop fighting and

cease-fire took effect on 1 January 1949.

The New Constitution and Quotas

In March 1948 Sheikh Abdullah was appointed the prime

minister of an interim government of the State. A Constituent Assembly was

convened in October 1951. The members of this Assembly were elected and

Sheikh Abdullah's National Conference won all its seats. In 1952 Jawaharlal

Nehru and Sheikh Abdullah signed an agreement in Delhi which specified that

the State of Jammu and Kashmir, while part of the Indian Union, yet enjoyed

certain unique rights and privileges within the Union. Thus citizens of the

State had rights related to land ownership within the State which were

denied to Indians from outside the State. This fact was recognized in

Article 370 of the Indian Constitution which was entitled " Temporary

provisions with respect to the State of Jammu and Kashmir" (Lamb 1966,

Puri 1981).

Curiously the restriction of land ownership to the

hereditary State subjects goes back to Hari Singh in 1927. This order also

reserved government posts to such residents. Hari Singh had become the

Maharaja two years earlier and he was trying to assert the autonomy of the

State from the British paramountcy. But he was also bowing to the interests

of the Hindus from Kashmir and Jammu who did not wish to have any

competition for the various administrative positions from people out of the

State. At that time the Kashmiri Hindus, with less than 2 per cent

population of the State, constituted 80 percent of all those who had

received higher education. This policy of reservation of jobs and

restriction of land ownership was opposed by the Muslims of the State and

outside. (Puri 1981)

Sheikh Abdullah was now trying to implement a

programme that had been outlined by the National Conference in 1944 in a

manifesto entitled New Kashmir . This amounted to a one-party government

dedicated to social reform in the style of the Soviet Union. Sweeping land

reforms were implemented in 1953. But there was also a suppression of

dissent and increasing bureaucratization with its attendent corruption.

Sheikh Abdullah's goal still appeared to be autonomy for the Kashmiris, but

he was unwilling to allow real democracy to the other regions of Jammu and

Ladakh. Growing tensions in the State led to his dismissal and detention in

August 1953. He was succeeded as prime minister of the State by Bakshi

Ghulam Mohammed who remained in power for 10 years.

The Constituent Assembly decided upon a

constitution which came into operation in January 1957. But this

constitution formalized inequities in the political structure that had seeds

in it for trouble down the road. The constituencies were delimited in a

fashion that perpetuated control by the Kashmiris of the Vale (Jagmohan

1991). The typical constituency in the Vale had a population of 50,000

whereas it was 85,000 in the Jammu region. For elections to the Lok Sabha,

Kashmir sent one representative for each one million people, while Jammu was

allocated one representative for each 1.4 million people. Furthermore, the

constituencies were so delimited that the Kashmiri Hindus, in spite of their

population of about 7% in the Vale, could not get a single member elected on

their own.

The fundamental rights of the Indian Constitution

were made applicable to the State in 1954; these forbade recruitment to

government jobs on communal and regional considerations. The government of

the State circumvented the law by declaring all the residents of the State

but the less than 3 percent Kashmiri Hindus to be backward. Quotas were now

fixed for recruitment based on ethnic origin and religion both for

recruitment and promotion (Puri 1983).

These policies split up the people of the State in

three main worlds: one Kashmiri Muslim, the other Hindu from Jammu, and the

third was that of the Kashmiri Pandit who was now discriminated against. A

system of quotas in schools, colleges, and jobs was instituted. These quotas

did not apply only at the entrance levels of the government departments but

also for promotion to higher ranks. This system was so perverted that the

candidates from the Muslim community were not chosen according to their

merit either. The bureaucratic system that emerged in Kashmir must have been

one of the most corrupt in India and the whole world.

It must be realized that the Muslims in Kashmir are

not a monolithic community. Caste in India is a phenomenon that transcends

religion (Leach 1960). Muslims in Kashmir, as Muslims elsewhere in India and

Pakistan, are socially divided into castes that have traditionally worked in

different occupations. Furthermore, the converts from the Brahmins,

Kshatriyas, as well as the descendents of the Turks, Afghans, and the

Iranians have generally maintained their identities and their status. Since

performance and skills were not determinants for hiring, the urban Muslim

elites, who were from a few select groups, were able to carve out a lions

share of government openings. The nature of the quota system makes it out as

an entitlement, so there was a great deal of resentment in the weaker Muslim

classes about this matter.

In the corrupt bureaucratic world of the two

Kashmirs, many of the small minority of the Hindus, who were traditionally

professionals, played the game according to the new rules. Others simply

left the State. And when the Central government expanded its bureaucracy in

the early seventies the Hindus joined in large numbers. Having been

systematically excluded from the State government jobs, the Hindus used

whatever access to power they had to obtain these jobs. No wonder,

therefore, that the Central government offices were perceived as being Hindu

as against the Muslim State government offices.

The division between the Hindus and the Muslims of

Kashmir was made worse by the Article 370 of the Indian Constitution which

gives a special status to the Jammu and Kashmir State. According to this

Article, apart from defence, foreign affairs, and communications the laws

enacted by the Indian parliament apply to the State only with the

concurrence of the State government. It is important to remember that this

Article was supposed to be of a transitional nature. But it came in handy to

the karkun elite who justified it by the rhetoric of socialism and

kashmiriyat (Kashmiriness). This law preserved the dominance of the Muslim

elite classes in Kashmir and they fought hard to preserve it. Politicians of

the ruling party made embrace of this Article to be axiomatic for a belief

in secularism. Anyone who questioned the wisdom of retention of Article 370

was dubbed a communalist, an obscurantist, and worse.

The psychology related to Article 370 made the

Muslims feel that their State was not quite a part of India. But this sense

of fostered apartness was the basis of the political alliances made

throughout India by the Congress Party to maintain political power. The

government controlled media harped on the themes of social justice and the

remedy of quotas and set-asides. Although this approach was useful for the

short-term political ends of the Congress Party and the National Conference,

it increased social discord and it kept out capital needed for economic

development in the State.

The forces unleashed by these policies led to a

progressively greater alienation of the Muslims in the State.

Fundamentalists seized upon this disaffection and they targeted the Kashmiri

Hindus as being representatives of the unjust order. They argued that Indian

polity had sunk into great divisions based on caste or regional origin and

that the Indian system is not blind to caste, ethnic background, or

religion. The fundamentalist in Kashmir said that if India is really not a

secular state, as evidenced by all the quotas and reservations based on

different criteria, the why should they not seek an Islamic, independent

nation, or accession to Pakistan.

The Accord of 1974 and After

After spending almost 14 years since 1953 in jail,

Sheikh Abdullah was finally set free in 1968. The defeat of Pakistan in the

1971 War and the consequent independence of Bangladesh seemed to ring the

death knell of the two-nation theory on which India had been partitioned.

This weakened the pro-Pakistan forces in the Valley considerably. Meanwhile

in 1972 India and Pakistan signed the Simla Agreement which effectively

superseded the U.N. role in Kashmir. Pakistan agreed to the Indian demand

that both countries will not resort to force or threaten to use force in

Kashmir and settle the issue bilaterally. In other words, foreign

interference, mediation or arbitration was to be precluded. The 1949

cease-fire line in Jammu and Kashmir was redrawn into a new Line of Control

which meant that the U.N. observers posted along the previous line became

redundant.

In March 1972, Sheikh Abdullah reiterated the

finality of the State's accession to India. In November 1974 he signed an

accord with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi which basically signaled his

acceptance of the existing political realities. When he resumed power as

Chief Minister in February 1975 he was welcomed tumultuously back in the

State. He now revived the National Conference Party and won a massive

mandate in the elections held in 1977.

Sheikh Abdullah now faced challenges from the

leaders of Jammu and Ladakh who pressed for autonomy for their regions.

Furthermore he was harried by the party of orthodox Islam as represented by

Jamait-e-Islami. The growing strength of the Jamait was no doubt due to the

growing fundamentalism in Islamic societies around the world after the

Iranian revolution. Sheikh Abdullah fought the Jamait for not respecting the

traditions of Kashmiri Islam.

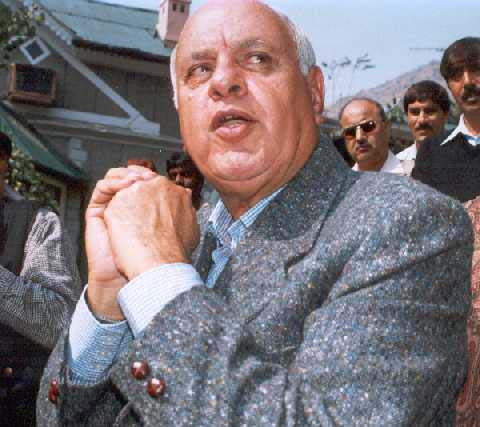

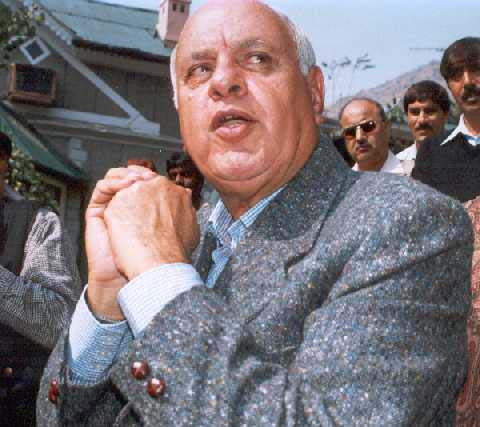

Sheikh Abdullah died in 1982. He was succeeded as

Chief Minister by his son  Farooq, who called Assembly elections in 1983 and

won a majority. In July 1984 Indira Gandhi dismissed Farooq's government for

mis-administration and installed G.M. Shah as the Chief Minister of a

minority government. Shah, who was Farooq's brother-in-law and a rival for

the leadership of the National Conference on Sheikh Abdullah's death, was

widely believed to represent the pro-Pakistan group in the party. The

administration became even more corrupt during his tenure. Now followed an

episode of Central rule to be succeeded by a return of Farooq. Farooq, who called Assembly elections in 1983 and

won a majority. In July 1984 Indira Gandhi dismissed Farooq's government for

mis-administration and installed G.M. Shah as the Chief Minister of a

minority government. Shah, who was Farooq's brother-in-law and a rival for

the leadership of the National Conference on Sheikh Abdullah's death, was

widely believed to represent the pro-Pakistan group in the party. The

administration became even more corrupt during his tenure. Now followed an

episode of Central rule to be succeeded by a return of Farooq.

The new administration of Farooq Abdullah was as

inept as the first one. The intrigues of the Congress Party increased the

distance between the ruling clique and the people. Meanwhile, the

pro-Pakistani elements subverted most government institutions. Then between

July and December 1989 the Farooq Abdullah government released seventy

hardcore terrorists. Soon civil administration literally collapsed.

Pakistani Direction of the Insurgency

With the Soviet Union taking sides in the Afghanistan

civil war that began in December 1979, Pakistan became strategically very

important to the U.S. President Zia ul-Haq of Pakistan decided to aid the

anti-communist Afghans who were fighting the Soviet troops. In 1981 Pakistan

received a six year aid package from the United States worth several billion

dollars. In addition the U.S. opened a pipeline through which sophisticated

weaponry flowed to the Afghan mujahiddin operating from their headquarters

in Peshawar. More arms and ammunition came from China, Egypt, and Saudi

Arabia. The field losses as well as a deteriorating home economy eventually

forced the Soviet Union to sign an agreement in April 1988 to withdraw from

Afghanistan by mid-February 1989.

This great success emboldened Zia now to try force

to pry Kashmir out of Indian control. The arms and equipment that had flowed

to the Afghan mujahiddin had been channeled by the Inter-Services

Intelligence (ISI). The ISI was now asked to plan and coordinate an

insurgency in Kashmir. This was to complement the training of the Sikh

militants which had been managed by the ISI for several years.

Although Zia died in a plane crash in August 1988,

his successors pressed on with management of the insurgency under the

control of the ISI. This involved running training camps for the militants,

supply of arms and intelligence. This operation was launched with full

intensity as the weak administration of Prime Minister Vishwanath Pratap

Singh took office in Delhi in late 1989. Kidnappings, bombings, and

assassinations and a literal abdication of governance by the Farooq Abdullah

ministry soon virtually achieved the administrative and psychological

severance of the valley from India.

Central rule was imposed on the State in January

1990. But with the money provided by Pakistan and Saudi Arabia and the arms

flowing in from the ISI warehouses the terror unleashed on the minority

communities of the Vale continued. Very soon the Hindus and the Sikhs had to

flee to Jammu and Delhi for the safety of refugee camps. The terrorist

groups were now hoping for a quick conclusion to their campaign. Banks, post

offices, schools, colleges, cinema halls were all forced to be shut down.

Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto talked of a thousand year war to liberate

Kashmir.

Refugees from the Vale

The terror has forced about 250,000 Kashmiris to seek

refuge out of the Vale. The Indian government is waiting for the law and

order situation to return to what it was in before the mass exodus began in

late 1989. A carrot and stick policy has been used to control the

insurgency. But the government does not appear to have done any rethinking

of its basic Kashmir policy.

In refugee camps the living conditions are very

poor. And now the exiles seek jobs wherever they can find them, howsoever

far from their homes that they have been compelled to abandon. Can that

unique tradition and culture that the Kashmiris have preserved and

reinvented with each generation be saved once they are scattered in

permanent exile out of the valley?

The government of India has tried to play down the

refugee problem since it smacks of religious strife. Many Muslims have also

been killed, and others have had to flee the valley. Recently the government

of India has raised this question of continuing murder of innocent civilians

by terrorists with sanctuaries in Pakistan in international forums. The U.S.

government has placed Pakistan on watch as one of the countries that sponsor

terrorism.

The crisis in Kashmir should not be viewed as

arising just from the alleged rigging of the last elections, the mis-administration

of the Farooq Abdullah years, and the Islamic fundamentalism that is

sweeping the world. This is the analysis that has been embraced by the

officials of the government of India. While this analysis has a ring of

truth to it, it is misleading. Events of the eighties have undoubtedly

contributed to the disaffection in the valley, but the seeds of separation

were laid by much older policies that are still in force.

The question of the alienation of the Kashmiri

Muslims has not been properly analyzed. Part of this alienation has a

linguistic basis. Although the Kashmiri language is different from the other

north Indian languages, all educated Kashmiris are bilingual. The second

language of choice for the Kashmiri Muslims is Persianized Urdu. This sets

them apart from the residents of Jammu or Kashmiri Hindus who have generally

adopted Sanskritized Hindi as the second language. Another contributing

factor is Islamic fundamentalism. But this alienation has been made worse by

the increasing bureaucratization of Indian life which causes untold

frustrations. A long-term solution to the Kashmir problem would require more

decentralization that proceeds down to the city and the village level. But

this restructuring must also sweep aside anachronistic statutes such as

Article 370 as well as other laws that discriminate based on religion and

caste.

Conditions for economic development and local

business initiatives will have to be improved. This will require clipping

the wings of the corrupt bureaucracy and elimination of the system of quotas

and licenses. Affirmative action should be based solely on economic

considerations. That is the only way traditionally disadvantaged Muslim

groups will be able to benefit from new development.

The bureaucratic style of administration that has

evolved in India is based on a reactive approach to problems. Many of the

frustrations that the citizen, be he Hindu or Muslim, feels are due to

excessive centralization. In the style of government that has been followed

in Delhi and in Srinagar, people have considered all problems in political

terms alone; this is natural given that the government runs the schools, the

banks, the colleges, and considerable part of business and industry.

A Democratic Kashmir

The international situation which emboldened Pakistan

to exploit the disaffection in Kashmir to organize an insurgency has passed.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union the strategic importance of Pakistan

to the West is much reduced. Pakistan's own internal problems will require

increasing attention from its leaders. It is, therefore, possible to look

beyond the current situation and visualize a return to near normalcy in the

Vale where most of the refugees will be able to return to their homes.

In the current geopolitical situation India cannot

let go of the Kashmir valley because of its strategic importance. Culturally

there are no reasons that the Kashmiris should feel more bound to Pakistan

than India, when India has about as many Muslims as Pakistan and India's

multicultural and secular society promises more freedom. But Kashmir's

relationship to India will become strong only if real democracy comes into

the Vale. This will require that schools, colleges, banks, and industry be

increasingly privatized. Such a privatization will weave a thousand

different links between organizations in Kashmir and the rest of India. But

this also means that Kashmir should get rid of restrictive laws of land

ownership and citizenship which have discouraged outside investment. A

modern State should treat all its citizens equally, irrespective of caste,

religion, and ethnic origin. The Jammu and Kashmir government, with the

tacit approval of the Centre, has not done this in the past. The policies of

quotas have served to divide the citizenry based on ethnic and religious

basis. Economic links forged between Kashmiris and Indians outside the Vale

would eventually determine the nature of their union.

Notes

According to the 1971 census the Kashmir valley had a

non-Muslim population of 6 percent. However, about 250,000 refugees, which

is more than 7 percent of the Vale's current estimated population, have

registered with government agencies. According to Facts Speak , Panun

Kashmir, Jammu the number of migrants was 242,758 in 53,750 families at the

end of November 1990. India Today , January 15, 1991 speaks of more than

55,000 migrant families. It appears, therefore, that the 1971 census might

have undercounted the population of the minorities in the Vale.

The

Legal Documents of Kashmir

References Cited

Ahmad, Aziz. 1969. An Intellectual History of Islam in

India . Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Bamzai, P.N.K. 1962. A History of Kashmir . Delhi:

Metropolitan Book Co.

Boyce, M. 1975. A History of Zoroastrianism .

Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Chatterji, J.C. 1914. Kashmir Shaivaism . Srinagar;

Reprint 1986, SUNY Press, Albany.

Drew, Frederic. 1875. The Jummoo and Kashmir

Territories . London: Edward Stanford. Reprinted 1976, Graz, Austria.

Dyczkowski, M.S.G. 1987. The Doctrine of Vibration

. Albany, SUNY Press.

Embree, Ainslie T. 1989. Imagining India. Essays on

Indian History. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Fox, Richard G. 1985. Lions of the Punjab: Culture

in the Making . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Geertz, Clifford. 1960. The Religion of Java . The

Free Press of Glencoe.

Gilmartin, David. 1988. Empire and Islam .

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gnoli, R. 1968. The Aesthetic Experience According

to Abhinavagupta . Benaras: Chowkhamba.

Heesterman, J.C. 1985. The Inner Conflict of

Tradition . Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Hefner, R.W. 1985. Hindu Javanese: Tengger

Tradition and Islam . Princeton University Press.

Jagmohan. 1991. My Frozen Turbulence in Kashmir .

New Delhi: Allied.

Jalal, Ayesha. 1990. The State of Martial Rule.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kachru, B.B. 1981. Kashmiri Literature. Wiesbaden:

Otto Harrassowitz.

Kak, S.C. 1990. Religion and Politics in East

Punjab. Journal of Social, Political, and Economic Studies. 15, 435-456.

Kak, S.C. 1991. The Politics of Quotas in South

Asia. Journal of Social, Political, and Economic Studies. 16, 401-421.

Kaul, R.N. 1985. Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah . New

Delhi: Sterling Publishers.

Kaw, R.K. 1967. The Doctrine of Recognition .

Hoshiarpur: Vishveshvaranand Institute.

Kipp, R.S. and Rodgers, S. 1987. (Editors)

Indonesian Religions in Transitions . Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Lakshman Jee, Swami. 1988. Kashmir Shaivism .

Albany: State University of New York Press.

Lamb, A. 1966. The Kashmir Problem . London:

Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Leach, E.R. 1960. Aspects of Caste in South India,

Ceylon and North-West Pakistan . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Madan, T.N. 1989. Family and Kinship: A study of

the Pandits of Rural Kashmir . Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Mujeeb, M. 1967. The Indian Muslims. London: George

Allen & Unwin.

Odin, Jaishree 1994. Lalla: The Woman and the Poet.

(Book in preparation)

Pandey, K.C. 1963. Abhinavagupta: An Historical and

Philosophical Study . Benaras: Chowkhamba.

Puri, Balraj. 1981. Jammu and Kashmir: Triumph and

Tragedy of Indian Federalisation. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers.

Puri, Balraj. 1983. Simmering Volcano: Study of

Jammu's Relations with Kashmir. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers.

Sender, Henny. 1988. The Kashmiri Pandits. Delhi:

Oxford University Press.

Shaikh, Farzana. 1989. Community and Consensus in

Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Singh, Jaideva. 1977. Pratyabhijnahrdayam . Delhi:

Motilal Banarsidass.

Singh, Jaideva. 1979. Vijnanabhairava or Divine

Consciousness . Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Singh, Jaideva. 1989. Abhinavagupta: A Trident of

Wisdom . State University of New York Press.

Singh, Raghubir 1983. Kashmir: Garden of the

Himalayas . London: Thames and Hudson.

Stein, M.A. 1979. (reprint) Kalhana's Rajatarangini:

A Chronicle of the Kings of Kashmir . Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Sufi, G.M.D. 1948-9. Kashir: Being a History of

Kashmir from the Earliest Times to Our Own. Lahore: University of the Panjab.

Reprinted Delhi, 1974.

Temple, R.C. 1924. The Word of Lalla the Prophetess

. Cambridge University Press.

Younghusband, F. 1909. Kashmir. London: Adam &

Charles Black.

|

against the Kashmiri

minorities by Muslim fundamentalists and an insurgency against the Indian

government. Within a year hundreds of selective and random murders forced nearly

all the Kashmiri Hindus and Sikhs, who comprise less than 10 percent of the

population of the Vale, to leave their homes for refuge in the Jammu province

and in Delhi.

against the Kashmiri

minorities by Muslim fundamentalists and an insurgency against the Indian

government. Within a year hundreds of selective and random murders forced nearly

all the Kashmiri Hindus and Sikhs, who comprise less than 10 percent of the

population of the Vale, to leave their homes for refuge in the Jammu province

and in Delhi.

century, was a powerful advocate of the Kashmiri

Muslims. His political career was launched when he galvanized his people to

agitate for reforms in 1931 during the rule of Hari Singh (Kaul 1985). Next

year a political party, Muslim Conference, was formed with Abdullah as its

first president. Under pressure from the British the Maharaja set up a

Commission to study constitutional reforms in the State. The recommendations

of this Commission led to the establishment of a legislative assembly of

seventy five members, thirty three of whom would be elected on a communal

basis, and an extremely limited franchise. When first convened in 1934, 19

of the 21 seats allotted to the Muslims were won by the Muslim Conference.

century, was a powerful advocate of the Kashmiri

Muslims. His political career was launched when he galvanized his people to

agitate for reforms in 1931 during the rule of Hari Singh (Kaul 1985). Next

year a political party, Muslim Conference, was formed with Abdullah as its

first president. Under pressure from the British the Maharaja set up a

Commission to study constitutional reforms in the State. The recommendations

of this Commission led to the establishment of a legislative assembly of

seventy five members, thirty three of whom would be elected on a communal

basis, and an extremely limited franchise. When first convened in 1934, 19

of the 21 seats allotted to the Muslims were won by the Muslim Conference.

Farooq, who called Assembly elections in 1983 and

won a majority. In July 1984 Indira Gandhi dismissed Farooq's government for

mis-administration and installed G.M. Shah as the Chief Minister of a

minority government. Shah, who was Farooq's brother-in-law and a rival for

the leadership of the National Conference on Sheikh Abdullah's death, was

widely believed to represent the pro-Pakistan group in the party. The

administration became even more corrupt during his tenure. Now followed an

episode of Central rule to be succeeded by a return of Farooq.

Farooq, who called Assembly elections in 1983 and

won a majority. In July 1984 Indira Gandhi dismissed Farooq's government for

mis-administration and installed G.M. Shah as the Chief Minister of a

minority government. Shah, who was Farooq's brother-in-law and a rival for

the leadership of the National Conference on Sheikh Abdullah's death, was

widely believed to represent the pro-Pakistan group in the party. The

administration became even more corrupt during his tenure. Now followed an

episode of Central rule to be succeeded by a return of Farooq.

No one has commented yet. Be the first!