Kashmir Dispute - The

Myth

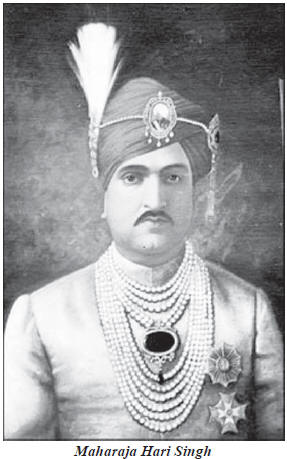

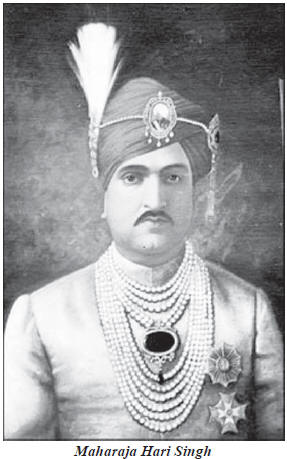

History vindicated Maharaja Hari

Singh's Stand

By Dr. M.K. Teng

Neither

the composition of the population of the Princely

States nor the self-determination of their peoples

was recognised by the British, the Muslim League

and the Indian National Congress, as the

determining factor of the future disposition for

the states in respect of their accession.

After the 3 June Declaration, envisaging the

partition of the British India, Nehru demanded the

right of the people of the Princely States to

determine their disposition in respect of their

accession Mohammad Ali Jinnah rejected Nehru's

demand as an attempt to thwart the process of the

partition. Shortly, before the transfer of power,

the Governor General of India, Lord Mountbatten

advised the Princess to keep in consideration the

geography and the composition of the population of

the States in reaching a decision on their

accession. Mountbatten proposed to the Muslim

League as well as the Congress to accept the

principles of the partition–geographical

contiguity and the composition of the population

as the criteria of their accession. While the

Congress leaders indicated their inclination to

accept the proposals, the Muslim League leadership

reacted sharply against the proposals and

characterised them as an attempt to interfere with

the rights of the Princes to determine the future

of the States. At that time the Muslim League was

deeply involved in shadowy maneuvers to support

the Muslim rulers of several major States to

remain out of India and align with Pakistan. It

has been pointed out in an earlier part of this

paper that Pakistan invoked the partition to

legitimize its claim to Jammu and Kashmir on the

basis of the Muslim majority character of its

population after the last two Muslim ruled States

of Junagarh and Hyderabad were integrated with

India.

There is enough historical evidence available,

which reveals that in persuading the Congress

leaders to accept the partition the British

assured the Congress leaders that after the Muslim

majority provinces and regions were separated to

form the Muslim homeland of Pakistan, the unity of

the rest of India, including the states would be

preserved and not impaired any further.

The Indian leaders rejected the claim Pakistan

made to the Muslim majority States as well as the

Muslim ruled States, but they dithered when the

time to act and unite the States with India

arrived. Instead of taking active measures to

bring about the unification of the States with

India, they resorted to subterfuge..

The Indian leaders turned to Mountbatten and not

the people of the States to bring about their

integration with India. Mountbatten steered the

States Department to accept a balance between the

Muslim ruled States and the Muslim majority

States. The largest of the Muslim ruled States

were deep inside the Indian mainland. Neither

Gandhi nor Nehru objected to the course, the

Indian States Department followed.

The Viceroy did not forgive Hari Snigh for having

disregarded his advice to come to terms with

Pakistan. He refused stubbornly to deal with Jammu

and Kashmir independent of the Muslim States and

in the long run did more harm to Jammu and Kashmir

than anybody else in India did. He was the main

proponent of the policy of isolation, the Indian

leaders followed towards Jammu and Kashmir. The

way Mountbatten acted as the Governor General of

India till 15 August 1947, and the way he acted as

the Governor General of the Indian Dominion after

15 August 1947, left wide space open for Pakistan

to claim a separate freedom for the Muslim of

Jammu and Kashmir on the basis of the Muslim

majority character of its population. Not many

months after the Security Council adopted its

first resolution on Jammu and Kashmir in August

1948, the Muslims laid claim to a separate freedom

for them on the basis of the Muslim majority

character of the population.

The Government of India and the Indian political

leadership failed to rebut the claim made by

Pakistan and the Muslims in Jammu and Kashmir that

the state was on the agenda of the partition of

India. Not only that, the Government of India and

the Indian political leadership failed to refute

the claim made by the Muslims of the state to a

separate freedom, different from the freedom that

the Indian people were ensured by the Constitution

of India - a separate freedom which was determined

by the theological imperatives of Islam. The

Indian leaders overlooked the fact that the

conflict which led to the partition of India was

rooted in the claim the Indian Muslims made to a

separate freedom which drew its sanction from the

precept and precedent of religion.

The Muslim League followed a meticulously designed

plan to use the Muslim rulers of several major

Princely States, situated deep inside the Indian

mainland to bring about the fragmentation of

India. The Indian leaders walked into the trap

when they tried to balance the accession the

Muslim majority state of Jammu and Kashmir with

the accession of the Hindu majority States ruled

by the Muslim Nawabs like Bhopal, Hyderabad and

Junagarh. The strategy to refer the issue of the

accession to the people of these States

tantamounted to the acceptance of the Muslim claim

to a separate freedom, the Two-Nation theory

envisaged. The Indian proposals to Pakistan to

refer the accession of Junagarh with that

Dominion, accomplished by the ruler of the State

on the eve of the transfer of power, was a tame

recognition of the Muslim claim to a separate

freedom. When Pakistan made a counter-proposal to

hold a plebiscite in all the three States, the

Government of India was suddenly faced with a

catastrophic choice. It promptly rejected the

proposals made by Pakistan.

The Indian Government, for unknown reasons,

separated its offer to refer the accession of the

State to its people i.e. the Muslims for their

endorsement. Why did not the Indian Government

propose to refer the accession of Bhopal and

Trancore to the Dominion of India, to the people

of the two States? The rulers of both the States

were opposed to join India and their people took

to the streets and forced them to accede to India.

Hardly ten months after the accession of the Jammu

and Kashmir while the Indian armies were still

fighting to drive out the invading forces, United

Nations foisted a resolution on India which

envisaged a plebiscite to determine its final

disposition in respect of its accession. The

resolution of the Security Council, virtually

underlined the repudiation of the accession of the

State to India and opened the option for the

Muslims of the State to exercise their choice to

join Pakistan. The Security Council Resolution was

the first step in the process of the

internationalization of the claim of the Muslims

of the State to a separate freedom. The

Government of India cried hoarse that it had

rejected the Two-Nation Theory inspite of having

accepted the partition of India. But its

commitment to refer the accession of the State,

accomplished by Hari Singh to its people was a

tacit recognition of the right to a separate

freedom, which underlined the demand for Pakistan.

Another ten months after the August resolution of

the Security Council was adopted the Indian

Government took a fateful step and formally

recognised the right the Muslims for Jammu and

Kashmir to a separate freedom, when in May 1949,

it agreed to exclude Jammu and Kashmir from the

constitutional organisation of India. In November

1949, the Constituent Assembly of India

incorporated provisions in the Constitution of

India which left out the State from the

constitutional structure which it had evolved for

the Dominion as well as the Princely States which

had acceded to India and after years of labour.

The special provisions for the State, embodied in

the Constitution of India, stipulated the

application of only Article if the Constitution of

India to the State. A blanket limitation was

imposed upon the application of the rest of the

provisions of the Constitution of India to the

State. The Union Government was empowered to

exercise powers listed in the Central list of the

Seventh Schedule of the India Constitution only in

respect of defence, foreign affairs and

communications which corresponded with the powers

delegated by the State to the Dominion Government

by virtue of the Instrument of Accession.

The Interim Government of the State, constituted

by the National Conference insisted upon the right

to frame a separate constitution for the State,

which fulfilled the aspirations of the Muslims who

constituted a majority of its population. The

Interim Government arrogated to itself

unrestricted powers and ruled the State by decree

and ordinance. Within six years of its tenure, it

completed the task of the Muslimisation of the

State by enforcing the precedence of Islam and the

Muslim majority in its social, economic and

political organisation. In 1953, the Interim

Government claimed a separate freedom for the

Muslim ‘nation’ of Kashmir. The Indian leaders had

conceded to the Muslims the right to constitute a

Muslim State of Jammu and Kashmir on the

territories of India. Confronted by the demand for

a Muslim State outside the territories of India,

the Indian leaders were flustered. They refused to

countenance the Muslim demand for a separate

Muslim State of Jammu and Kashmir, which did not

form a part of India. The Interim Government was

dismissed and the National Conference broke up.

Pakistan, the Muslim separatist and pro-Pakistan

Muslim flanks joined by a large section of the

leaders and cadres of the National Conference,

called for a plebiscite in the State, which

enabled the Muslims to exercise their right of

self-determination. They claimed that they had

acquired in consequence of the partition of India

and which India, Pakistan as well as the United

Nations had explicitly recognised.

The Muslim separatist movement led by the

Plebiscite Front, committed itself to an

ideological framework which was based upon the

distortions of the history of the partition of

India. The ideological commitments of the

Plebiscite Front underlined : (a) that the

right of the Muslims to a separate freedom enmated

from the partition of India and the creation of

the Muslim homeland of Pakistan; (b) that

the right of the Muslims to a separate freedom

transcended the accession of the State to India,

brought about by the ruler of the State; and

(c) that as a consequence of the partition of

India, the Muslims, constituting the majority of

the population of the State, had acquired an

irreversible right to exercise their option to

join the Muslim State of Pakistan.

In 1990, the Muslim Jehad initiated by Pakistan

and the Muslim separatist forces in the State,

claimed their aims to be the unification of Jammu

and Kashmir with Pakistan on the basis of the

Muslim majority character of its population to

complete the agenda of the partition of India. The

Jehad claimed that Muslims of the State, as the

Muslims elsewhere in India, had acquired a right

to a separate freedom which the Muslim struggle

for Pakistan had secured the Muslim nation of

India.

The Indian Government and the Indian political

class must realise that the Muslims of the State

did not acquire any right to separate freedom from

the partition of India, which brought Pakistan

into being and any attempts to arrive at a

compromise with the Muslim separatists forces will

lead straight to a second partition of India. The

Muslim claim to a separate freedom on the basis of

religious is a negation of the unity of India.

Of the many distortions of the history of the

transfer of power in India, which form a part of

the Kashmir dispute, the most conspicuous is the

distortion of the historical facts of the boundary

demarcation between the Dominion of India and

Pakistan in the province of the Punjab. After the

announcement of the partition plan on 3 June,

1947, a Boundary Commission was constituted by the

British to demarcate the boundary between the

Muslim majority zones and the Hindu-Sikh majority

zones in the two provinces of Bengal and the

Punjab. The Boundary Commission for the

demarcation of the Muslim majority zone in the

Punjab was constituted of four Boundary

Commissioners, two of them representing the

Muslims and two representing Hindus and the Sikhs.

Justice Din Mohammad and Justice Mohammad Munir

represented the Muslims and Justice Mehar Chand

Mahajan and Justice Teja Singh represented the

Hindus and the Sikhs respectively. A British

lawyer of great repute, Sir Cyril Radcliff was

appointed the Chairman of the Commission. Sir

Radcliff presided over the Boundary Commission

appointed for the demarcation of the boundary in

the province of Bengal as well.

The Boundary Commission was charged with the

responsibility of demarcating the Muslim majority

region of the Punjab from the Hindu-Sikh majority

region of the province on the basis of the

population and other factors, which were

considered to be relevant to the division of the

province. Justice Mohammad Munir and Justice Din

Mohammad refused to agree upon the criteria to

specifically identify the factors other than

population ratios. The Muslim Commissioners

insisted upon strict adherence to the population

proportions as the basis of the division of the

province.

Mehar Chand Mahajan and Teja Singh pleaded for a

balanced interpretation of the terms of reference

of the Boundary Commission and emphasised the need

to bring about harmonization between population

proportions and the "other factors", specified in

the terms of reference. They felt that the

division of the province of the Punjab was bound

to affect the lives of millions of people,

belonging to various communities living in the

province as well as the future of the two

Dominions, India and Pakistan. The Commissioners

pointed out to the Commission that the population

of the Hindus and Sikhs was unevenly distributed

over the province of the Punjab. They pointed out

that larger sections of the Hindu and Sikh

population were concentrated in relatively smaller

region of the East Punjab and the imbalance would

be reflected in demarcation of Hindu and Sikh

majority regions from the Muslim majority regions

of the West Punjab. They expressed the fears that

the territorial division of the Punjab on the

basis of population would earmark a smaller part

of the East Punjab, to the Hindu and Sikh

Community which would not commenserate with their

population in the province. The Hindus and the

Sikhs, Mahajan and Teja Singh pointed out to the

Commission formed 45 percent of the population of

the province and the territorial division of the

province on the basis of the population ratios

would leave them with less than 30 percent of the

territory of the Punjab.

Mahajan and Teja Singh pointed out to the

commission that fair distribution of river waters,

irrigation headworks and canal system and cultural

and religious centres could not be left out of its

consideration in the delimitation of the Muslim

majority and the Hindu and Sikh majority regions

of the province. They emphasized the necessity of

keeping in view the geographical contiguity of the

demarcated regions, the communications and the

viability of the borders of the two Dominions of

India and Pakistan. They told the Commission that

in the demarcation of the borders between the West

Punjab and the East Punjab balance would have to

be achieved to ensure a fair and equitable

division of the territories of the province

between the Muslim community and the Hindu and the

Sikh communities.

The most controversial and bitterly contested part

of the demarcation for the borders was the

division of the Doab, comprising the districts of

the Lahore Division. Of the four districts of

Lahore Division, the District of Amritsar was a

Hindu-Sikh majority district and the district of

Gurdaspur was a Muslim majority district with the

Muslims having a nominal majority of 0.8 percent.

Both Din Mohammad and Mohammad Munir insisted upon

the inclusion of the entire Lahore Division in the

West Punjab. The Muslim Commissioners were men of

great ability and legal acumen and had the

advantage of representing the majority community

of the Punjab. They knew that the inclusion of the

Lahore Division in the West Punjab would be of

crucial importance to the future of Pakistan. The

inclusion of the Lahore Division in the West

Pakistan would ensure the Muslim homeland a larger

share of water resources, irrigation headworks and

the canal system of the Punjab. It would also

close the only communication line; the Jammu-Madhopur

fair weather road, which ran between the Jammu and

Kashmir State and the Dominion of India. The

Muslim League leaders were keen to isolate Jammu

and Kashmir and build pressure on the ruler of the

State to compel him to come to terms with

Pakistan. Jammu and Kashmir was not wholly

isolated from India and had a contiguous frontier

with Kangra and the Punjab Hill States, which had

acceded to India. The State Government could

construct an alternative communication route to

connect the State with India. The construction of

an alternative road between the State and the

Dominion of India would, however, be an arduous

task and take a long time, thus exposing the State

to more hardship. Logistically also the

construction of an alternative road would pose

many problems. The borders between the State and

the Indian Union running east of the Pathankot

tehsil in Gurdaspur district, through which the

Jammu-Madhopur road run, were mountainous and

rugged and largely snowbound. The closure of the

Jammu-Sialkot road and railway line and the Jhelum

Valley road, which linked Srinagar with Rawalpindi

had been closed by Pakistan and there was little

prospect of their being thrown open for transport

after the State joined India. By the time, the

Boundary Commission begun its work, Pakistan was

left with little doubt about the disinclination

for the ruler of the State Maharaja Hari Singh to

accede to that country.

Mahajan and Teja Singh pleaded for the inclusion

of the Division of Lahore in the East Punjab. The

two Commissioners raised fundamental issues with

unparalleled eloquence in respect of their claim,

which Sir Cyril Radcliffe could not overlook

altogether. The issues they raised, included:

i) the distribution of water resources between the

East and West Punjab, the location of the

irrigation headworks and the canal system;

ii) the continuation of the communication lines in

the East Punjab of which the Lahore Division

formed Centre;

iii) the demarcation of a viable and defensible

border of the India in the Punjab;

iv) the interests of the Sikh Community which had

its largest assets in the West Punjab and its main

religious and cultural centres in the Division of

Lahore;

v) the Indian interest in the road-link between

Jammu and Madhopur, arising out of its proximity

to Jammu and Kashmir State for the security of

that state as well as its future relations with

the Indian Dominion.

Both Mahajan and Teja Singh avoided the heavily

value-laden discourse of the Congress leaders, in

their presentation to the Commission. They

marshalled up concrete facts relevant to the

demarcation of boundary in the Punjab and

elucidated in detail the consequences -

geographic, economic, political and strategic, the

division of the province was bound to lead to and

their impact on the future of the Hindus and Sikhs

in the Punjab. Sir Radcliffe was a man of

independent outlook, sent down from his country to

draw the boundaries of the new Muslim State of

Pakistan, which the British had actively connvived

in creating. Sir Radcliffe knew little of the

cultural configuration of the Punjab, its economic

organisation and its history. Not only the Punjab,

Sir Radcliffe knew much less of the history and

culture and economic and political organisation of

Bengal, the other Indian province he was

commissioned to divide between the two

communities, Hindus and Muslims, on the basis of

population proportions.

Mahajan and Teja Singh were genuinely fearful of

the future of their communities in the Punjab. The

history of the Punjab had been shaped by Hindus

and the Sikhs. The Sikhs established a powerful

Kingdom in the Punjab, the borders of which

extended from Afghanistan to the eastern fringes

of Tibet. The Sikh state integrated the Himalayas

into the northern frontier of India. The

Himalayas, Sanskritised by the Hindus of Kashmir,

formed the civilisational frontier of India. The

establishment of the Sikh power put an end to the

long history of the invasion of India from the

north. The division of Punjab was bound to have

serious effect on the future of the Sikh

community. The Punjab was considered by the Sikhs

to be their homeland. The Sikh places of

pilgrimage were located in the eastern part of the

Punjab, mainly the Division of Lahore. The

responsibility of apprising the Boundary

Commission of the sociology of the Sikh religion

and its moorings in the Hindu civilisation of

India, fell upon the Hindu and Sikh Commissioners.

Teja Singh, ravaged by the anti-Hindu riots in the

Punjab, exhibited great courage and forbearance,

in defending the cause of his community.

The Muslim League carried on a strident campaign

to build pressure on the Commission to demarcate

the boundary between the east and the West Punjab

on the basis of the population proportions. The

British Governors of the Punjab and the North-East

Frontier province along with the British officials

posted in the two provinces acted in tandem to

influence the Commission.

The Boundary Commission was entrusted with the

historic task, of the demarcation of the Indian

frontier in the north. Jammu and Kashmir formed

the central spur of the warm Himalayan uplands and

the new configuration of power created by the

emergence of the Muslim state of Pakistan, was

bound to effect the security of the Himalayas.

There is no evidence to show that the Indian

leaders realised the importance of the crucial

changes, the emergence of Pakistan, would bring

about in the structure of power-relations along

northern frontier of India.

The Hindu and Sikh leaders of the Punjab evinced

serious interest in the boundary demarcation. Both

Mahajan and Teja Singh kept themselves in close

touch with the Hindu and Sikh leaders of the

Punjab. Among them were Sir Shadi Lal and Bakshi

Tek Chand. Both Sir Shadi Lal and Tek Chand were

in the confidence of Maharaja Hari Singh. The

Indian leaders had warbled notions about the

northern frontier of India. They were carried away

by the fraternal regard, the Asian conference held

in Delhi in 1946, symbolised. The Indian leaders

viewed the solidarity of the Asian people and the

emergence of the Asian nation from colonial

dominance as basis for coexistence and cooperation

among the Asian people. Gandhi disclaimed national

frontiers. He claimed commitment to vaguely

conceived concept of anarchism which formed a part

of the intellectual tradition of the early

twentieth century.

They had accepted partition of India, but they

refused to recognise its political implications.

They were unable to comprehend the significance of

the demarcation of the boundary between India and

Pakistan in the Punjab. Their inability to link

the boundary demarcation in the Punjab with the

security of the Northern Frontier of India exposed

Jammu and Kashmir and the entire Indian frontier,

stretching to its east, to foreign aggression.

Another man, whose future was linked with the de

marcation of the boundary in the Punjab, was

Maharaja Hari Singh, the ruler of Jammu and

Kashmir. The Jammu-Madhopur fair weather cart-road

was the only communication link between the State

and India. The two major all weather motorable

roads, the Jehlum-Valley Road linking Srinagar

with Rawalpindi and the Jammu-Sialkot road ran

into the West Punjab. The railway line connecting

Jammu with Sialkot also ran into the West Punjab.

The border between the State and Kangra and the

Punjab Hill States, which had decided to accede to

India, was broken by rugged mountainous terrain.

An alternate road could be built via Mukerian to

connect Jammu with Kangra and via Doda with the

Punjab Hill States. Indeed, when Mahajan and Teja

Singh pointed out to the Commission the necessity

of securing access to Jammu and Kashmir through

East Punjab, Mohammad Munir and Din Mohammad

suggested the construction of an alternate land

route via Mukerian connecting Jammu with Kangra.

The Hindu and the Sikh Commissioners realised, as

did Hari Singh, the importance of the tehsil of

Pathankot to the viability and the defensibility

of the borders of India as well the Jammu and

Kashmir State.

Sir Shadi Lal and Bakshi Tek Chand kept Hari Singh

informed of the boundary demarcation in the

Punjab. They were close to Mehar Chand Mahajan and

had apprised him of the interest Hari Singh had in

the demarcation of the boundary in the Punjab.

Hari Singh was suspicious of Mountbatten, whose

mind he knew. He did not trust the Congress

leaders. He had received a communication from

States Minister, in which the latter had advised

him to release the National Conference leaders and

come to terms with them. Unsure of the course Sir

Radcliffe would follow in respect of his State, he

reportedly, conveyed to the British officials,

through some of his trusted British friends, his

interests in a balance border with the two

Dominions of India and Pakistan and the importance

of the Jammu-Pathankot road for the security of

his State. Reportedly, he conveyed to the British

authorities that in case he was not secured the

land route between Jammu and Pathankot he would

have no other alternative except to depend upon

the Dominion of India for the construction of a

new transit route, across the eastern borders of

the State with Kangra or with any of the Punjab

Hill States, which had already acceded to India.

The British were not averse to a balanced border

of the State with India and Pakistan, for they

were keen to avoid any diplomatic or political

lapse which would push the Maharaja into the lap

of India. Some of the British officials sincerely

believed that Hari Singh would opt for an

arrangement in which he was not required to accede

to any of the Dominions, if he was guaranteed

peace on his frontiers. Ram Chander Kak, out of

stratagem or straight devotion to his master, had

spared no efforts to assure the British, that Hari

Singh pursued a policy, which enabled him to

retain his independence, rather than join India

which was beset with serious difficulties.

In view of the extremely divergent views and deep

disagreement among the Hindu and Sikh

Commissioners and the Muslim Commissioners, the

Boundary Commission was unable to reach a mutually

acceptable agreement on the demarcation of the

boundary across the Lahore Division. In accordance

with the procedure laid down for the Boundary

Commission, in case of disagreement among the

Hindu, Sikh and the Muslim representation in the

Commission, it was decided by mutual agreement to

entrust the task of the demaracation to Sir

Radcliffe, the Chairman of the Boundary

Commission. The Commissioners, representing the

Hindus and the Sikh as well as the Muslims agreed

that the arbitral award made by Sir Radcliffe

would be binding on them.

History had cast a unique responsibility on Sir

Radcliffe, to lay down the future boundaries of

the nation of India, which was on the threshold of

freedom from centuries of slavery as well as

describe the future boundaries of an independent

Muslim state in India. The Congress leaders, were

perhaps, oblivious of the elemental change the

creation of Pakistan would bring into the

civilisational boundaries of India and the

far-reaching effect the establishment of a Muslim

power in India, would have on its northern

frontiers. Jammu and Kashmir formed the central

spur of the great Himalayan uplands poised as the

State was, it stood as a sentinel for any eastward

expansion of any power from the west as well as

the north.

Pakistan was, however, keenly conscious of the

strategic importance of Jammu and Kashmir. But the

Government of Pakistan was unable to judge the

ability of Maharaja Hari Singh to defeat their

designs. Hari Singh played a historic role in

persuading Sir Radcliffe to accept that his State

could not be completely isolated from the Indian

Dominion.

The Muslim League leaders did not trust Hari

Singh. They spared no efforts to convince the

British officials in the Government of India about

the necessity to ensure that the Boundary

Commission did not deviate from the principle of

the population proportions. The Muslim League

leaders were keen to acquire the

Ravi Headworks at Madhopur isolate the district of

Amritsar and seal the existing road-link

connecting Jammu and Kashmir with India.

The League leaders sent Chowdhary Mohammad Ali to

convey to the British officials in the Indian

Government their concern about the future of the

Lahore Division. Mohammad Ali met, Lord Ismay, the

Political Advisor to the Viceroy to convey to

Mountbatten the anxiety of the Muslim League

leaders about any deviation from the principle of

population-proportions the Boundary Commission may

resort to in the demarcation of the boundary in

the Punjab. Ismay told Mohammad Ali that the

Boundary Commission was an independent body of

which the functions were determined by its terms

of reference, and the Government of India had no

role in its function. Many years later, research

in Pakistan revealed that during his meeting with

Lord Ismay, Mohammad Ali showed the Political

Advisor a sketch map of the demarcation of the

boundary between east and west Punjab which was

not strictly based upon the principle of

population-proportions. Ismay, reportedly

expressed dissatisfaction with it.

The award of the Boundary Commission was announced

on 18 of August 1947, three days after the

transfer of power in India. Sir Radcliffe left

India the same day. The districts of Amritsar and

Gurdaspur were included in the East Punjab,

whereas the districts of Lahore and Sheikhopora

were included in the West Punjab. The entire

Muslim League leadership flared upon in anger

against the inclusion of Gurdaspur in the East

Punjab and blamed Sir Radcliffe of connivance in a

craftily devised plan to give India access to

Jammu and Kashmir and provide the Indian state the

strategic ground to grab the State. Communal riots

flared up in Lahore and spread to the whole of the

Punjab.

Sir Radcliffe followed uniform standards in the

delimitation of the boundary between India and

Pakistan in Bengal as well as the Punjab.

Evidently, he did not overlook the consideration

of other factors, specifically mentioned in the

terms of reference of the Boundary Commission in

the delimitation of the boundary between the East

and the West Punjab. He did take into

consideration the nominal majority, the Muslims

enjoyed over the Hindus and the Sikhs in Gurdaspur.

The Tehsil of Pathankote in the Gurdaspur district

had a distinct Hindu majority and it could not

have been included in the West Punjab by any

stretch of imagination. Sir Radcliffe had not

followed the district boundaries as the basis of

delimitation of the boundaries elsewhere in the

Punjab. Besides, the Ravi irrigation headworks

were located in Pathankot and they could not have

been excluded from the East Punjab, to ensure a

just and equitable distribution of water resources

in the Punjab between India and Pakistan.

undoubtedly, Sir Radcliffe did not overlook the

necessity of providing a balanced border to the

Jammu and Kashmir State, for which Mahajan and

Teja Singh had spiritedly pleaded. The security

of the Jammu and Kashmir State, which constituted

the central spur of the northern frontier of India

and which was crucial to the security of the

Himalays, could not be left out the consideration

of the Boundary Commission. The division of the

Punjab was a part of the partition of India and

the demarcation of the boundary between India and

Pakistan could not be undertaken in isolation from

its effects on the Indian States. The delimitation

of the boundary in the Punjab around the

Bahawalpur State, was undertaken with due

consideration of its future affiliations.

Bahawalpur joined Pakistan,.

Sir Radcliffe recognised the inclusion of the

district of Gurdaspur in the East Punjab as a

strategic requirement of the security of the

northern frontier of India, including the frontier

of India in the Punjab. He accepted in his report

that the inclusion of Gurdaspur in the East Punjab

was necessary for the security of the district of

Amritsar, which would otherwise he surrounded by

Pakistan. Perhaps, Radcliffe was aware of the

security of the northern Frontier of India, in

which the British were more interested than the

Congress leaders, who had warbled notions about

the security of the Himalayas. Unlike the other

officials of the Government of India, Radcliffe

was free of the trappings, the British officials

of the Indian Civil Service were strapped to. He

did not visualise the partition of India as the

British officials of the Indian Government did,

and he was guided by his own judgement. He

refused to recognise the claim to the geographical

expression of the Muslim nation of

Pakistan, the way the British officials of the

Indian Government did. He had little regard for

their colonial concerns or Jinnah's notions of the

ascendance of the Muslims power in India.

An important consideration which Sir Radcliffe had

in mind in dividing the Lahore Division was the

future of the Sikh Community, which was bound to

be adversely affected by the partition of the

Punjab. The land and the assets owned by the Sikhs

were largely situated in the west Punjab but a

larger section of their population lived in the

East Punjab. Besides, their main religious centres

and most sacred shrines, including the Durbar

Saheb, were located in the Lahore Division. The

division of the Punjab was bound to uproot them

from the West Pakistan and deprive them of their

land and assets. The claim laid by the Muslims to

the whole of Lahore Division, would divest them of

their sacred places and shrines. Lahore was the

seat of the Sikh empire of the Punjab, which had

changed the course of the history of India. The

demarcation of the boundary of the East Punjab was

therefore, crucial to the survival and future of

the Sikh community. Both Mahajan and Teja Singh

emphasised upon the need to consider the interests

of the Sikh community in the demarcation of the

boundary in the Punjab.

The inclusion of Gurdaspur in the East Punjab

mitigated, though only partially, the rigours of

the division of the Punjab.

The delimitation of the boundary in the Punjab,

Sir Radcliffe undertook, gave the Muslims, who

constituted 55 percent of the population of the

Province, 65 percent of its territory. The Hindus

and the Sikhs who constituted 45 percent of the

population got only 35 percent of the territory of

the Punjab. The Muslim League leaders had no

reason to grumble. Their reconstruction were

politically motivated and aimed to prepare ground

to launch a new form of Direct Action to reduce

the Jammu and Kashmri State.

Pakistan resorted to the distortion of the history

of the transfer of power in India, to justify its

claim on Jammu and Kashmir. Inside Jammu and

Kashmir the National Conference leaders who ruled

the State for decades after its accession to

India, resorted to the distortion of the history

of the accession of the State to India, to

legitimize their claim to a Muslim State of Jammu

and Kashmir inside India but independent of the

Indian Union and its political organisation. Not

only that. The Muslim separatists forces, which

dominated the political scene in the State after

the disintegration of the National Conference in

1953, also resorted to the fossilization of the

facts of the accession of the State to India.

Interestingly, the entire process of the

distortion of the history of the accession of the

State, spread over decades of Indian freedom

assumed varied expressives from time to time.

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah who headed the Interim

Government instituted in March 1948, disclaimed

the Instrument of Accession executed by Hari

Singh, as merely the Kagzi Ilhaq' or "paper

Accession" and claimed that the "real accession of

the state to India" would be accomplished by the

people of the State, more precisely the Muslim

majority of the people of the State. While the

Constitution of India was on the anvil and the

issue of the constitutional provisions for the

States came up for the consideration for the

Constituent Assembly of India, Sheikh Mohammad

Abdullah claimed that the National Conference had

endorsed the accession of the State to India on

the condition that the claim the people of the

state had to a separate freedom was recognised by

India and the leadership of the National

Conference had been assured by the Indian leaders

that the people of Jammu and Kashmir would be

reserved the right to constitute Jammu and Kashmir

into an autonomous political organisation,

independent of the Indian constitutional

organisation.

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and other National

Conference leaders, claimed that they had been

assured that Jammu and Kashmir would not be

integrated in the constitutional organisaion of

India and the assurances were incorporated in the

Instrument of Accession. They stressed that they

had agreed to the accede to India on the specific

condition that the Muslim identity of the State

would form the basis of its political organisation.

In his inaugural address to the Constituent

Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir convened in 1951,

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah who was the Prime

Minister of the Interim Government of the State,

claimed that the Constituent Assembly was vested

with the plenary powers, drawn from the people of

the State and independent of the Constitution of

India. He claimed that the Constituent Assembly

was vested with the powers to opt out of India and

assume independence or join the Muslim state of

Pakistan.

Fifty years later the claims Sheikh Mohammad

Abdullah made in the Constituent Assembly were

echoed in the first Round Table Conference,

convened by the Government of India in 2006, to

reach a consensus on a future settlement of the

Kashmir dispute.

Mr Muzaffar Hussain Beg, represented the People

Democratic Party in the Round Table Conference

which was a constituent of the coalition

government in the State, headed by the Congress

Party. Beg claimed, that the Instrument of

Accession was a treaty between two independent

states, the Dominion of India and the Jammu and

Kashmir State and the Constituent Assembly was a

sovereign authority, independent powers inherent

in its sovereignty.

The Government of India made no efforts to put the

record straight. Frightened at the prospect of

losing the support of the National Conference the

Indian leaders did not question the veracity of

the claims the Conference leaders made. Indeed,

they depended upon the support of the National

Conference to win the plebiscite which the United

Nations Organisation was hectically preparing to

hold in the State. The Indian leaders, overwhelmed

by their own sense of self-righteousness, helped

overtly and covertly in the falsification of the

history of the integration of the Princely States

with India and the accession of Jammu and Kashmir

with the Indian Dominion in 1947. Many of them

went as far as to link the unity of India with the

reassertion of the subnational identity of Jammu

and Kashmir, which the Muslim demand for separate

freedom for the Muslim symbolised.

The Indian Independence Act of 1947, laid down

separate procedures for the transfers of power in

the British India and the Indian Princely States.

The Princely States were left out of the partition

plan, which divided the British Indian provinces

and envisaged the creation of the Muslim state of

Pakistan. In respect of the Princely States, the

Indian Independence Act, envisaged the lapse of

the paramountcy - the power which the British

Crown exercised over the Indian States. The

British Government clarified its stand on the

future disposition of the States in the British

Parliament during the debate on the Indian

Independence Bill. It categorically stated that

the lapse of the Paramountcy would not enable the

Princes to acquire Dominion status or assume

independence.

The British Government made it clear that the

reversion of the Paramountcy to the rulers of the

States would inevitably lead to mutually accepted

agreements between the Dominions and the Princely

States which would involve their accession. The

Indian Independence Act did not envisage in the

procedure the accession of States. The Nawab of

Bhopal approached the Diplomatic Mission of the

United States of America in India to seek the

recognition of the Independence of his state. The

American Government snubbed the Nawab and refused

to countenance any proposals for the independence

of the Princely States in India. It was left to be

formulated by the two Dominions of India and

Pakistan.

The Political Department of the British Government

of India was divided into two separate Political

Departments – the Political Department of Pakistan

to deal with the Indian Princely States. The

Political Department of India was put in charge of

Sardar Vallabhai Patel and the Political

Department of Pakistan was put in charge of Sardar

Abdur Rab Nishtar. The procedure for the accession

of the States to the two Dominions was evolved

separately by their respective Political

Departments.

The Muslim League however, insisted upon the

independence of the Princely States in order to

enable the Muslim ruled states to remain out of

India. The Muslim League aimed to Balkanise the

Princely States and place the state of Pakistan in

a position which provided it a way to forge an

alliance with them. The Indian States spread over

more than one-third of the territory of India

constituted more than one fourth of the Indian

population. Some of the Muslim ruled Princely

States were largest among the Princely States of

India and several of them were fabulously rich.

The claim Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah made in his

inaugural speech to the Constituent Assembly of

the State that the States had the option to assume

independence was a reiteration of the stand the

Muslim League had taken on the future disposition

of the states following the lapse of the

Paramountcy. The lapse of the Paramountcy did not

underline the independence of the States. It did

not envisage the reversion of any plenary powers

to the Princes or the people of the states as a

consequence of the dissolution of the Paramountcy.

The states were not independent when they were

integrated in the British Empire in India. They

did not acquire independence when they were

liberated from the British Empire 1947. They were

not vested with any inherent powers to claim

independence to which Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah

referred to in his inaugural address to the

Constituent Assembly.

The convocation of the Constituent Assemblies in

the States was provided for in the stipulations of

the Instrument of Accession that the Princely

States acceding to India, executed. The Instrument

of Accession devised by the States Department of

Pakistan for the accession of the States to that

country did not envisage provisions pertaining to

the convocation of the Constituent Assembly. The

power to convene separate Constituent Assemblies

was reserved for all the major states the Union of

the States, which acceded to India.

The Jammu and Kashmir State was no exception. In

fact, Constituent Assemblies were convened, in the

states of Cochin and Mysore and the State Union of

Saurashtra, shortly after their accession to the

Indian Dominion.

The Constituent Assembly of Jammu and Kashmir was

a creature of the Instrument of Accession. It

exercised powers which were drawn from the state

of India and its sovereign authority. It did not

assess any powers to revoke the accession of the

State to India to bring about the accession of the

State to Pakistan or opt for its independence, as

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah in his inaugural address

to the Constituent Assembly claimed or as Mr

Muzaffar Hussain Beg claimed in the Round Table

Conference.

The truth of what happened during those fateful

days of October 1947, when the accession of Jammu

and Kashmir to India was accomplished was

concealed by a irredentist campaign of

disinformation which was launched to cover the

acts of cowardice and betrayal, subterfuge and

surrender which went into the making of the

Kashmir dispute.

The National Conference leaders, were at no stage,

brought in to endorse the accession of the State

to India. No one among them was required to sign

or countersign the accession and none of them

signed or countesigned the Instrument of

Accession, executed by Maharaja Hari Singh. The

Indian Independence Act, an Act of the British

Parliament, which laid down the procedure for the

transfer of power in India, did not recognize the

right of self-determination of either the people

of the British India or the people of the States.

The transfer of power was based on an agreement

among the Congress, the Muslim League and the

British. The British and the Muslim League

stubbornly refused to recognise the right of the

people of the British India and right of the

people of the Princely State to determine the

future of the British India or the Indian states.

The Muslim League and the British insisted upon

the lapse of the Paramountcy and its reversion to

the rulers of the States. Accession of the States

was not subject to any conditions and the

Instrument of Accession underlined an irreversible

process the British provided for the dissolution

of the empire in India.

No assurance was given to the National Conference

leaders that the Constituent Assembly of the State

would be vested with plenary powers or powers to

ratify the accession of the State to India, revoke

it opt for its independence or its accession to

Pakistan. Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and the other

National Conference leaders did not seek the

exclusion of the State from the Indian political

organization as a condition for the accession of

the state to India. Nor did the Indian leaders

give any assurance to them that the Jammu and

Kashmir would be reconstituted into an independent

political organisation, which would represent its

Muslim identity.

At the time of the transfer of power in India, the

National Conference leaders and cadres were in

jail. They were released from their incarceration

after the proclamation of General Amnesty was made

on 6 September 1947. Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, the

Acting President of the National Conference who

had evaded arrest and taken refugee in the British

India in May 1946, arrived in Srinagar with

several other senior leaders of the National

Conference on 12 September 1947. Meanwhile,

Mohi-ud-Din Qara the Director General of the War

Council, which had been constituted by the

National Conference to direct the Quit Kashmir

Movement, surfaced from his underground quarters

alongwith some of his close aides. Onkar Nath

Trisal, who played a historic role in the defence

of Srinagar, when the invading armies of Pakistan

surrounded the city, was with him. Sheikh Mohammad

Abdullah was released from jail on 29 September

1947.

Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad used the good offices of

Pandit Sham Sundar Lal Dhar, a personal aide of

the Maharaja to arrange a reconciliatory meeting

between Hari Singh and Sheikh Mohammd Abdullah.

The meeting did not go beyond usual formalities as

the two men who shaped the future of the State

looked at each other with cold distrust. Shiban

Madan, a close kin of Sham Sundar Lal Dhar, then a

man of younger years acted as a help. Shiban Madan

told the author in a interview held in Srinagar in

1978, that Hari Singh sat through the meeting

glumly. His Highness looked straight when the

usual presentation ceremony of the Nazarana was

completed. He sat glum and expressionless, his

haughty demeanour more than awkwardly visible. The

rest of the meeting was strictly formal."

Hari Singh was unable to judge the far-reaching

consequences of the end of the British empire in

India. Not only him, the other Princes too refused

to realise that their power, which had its

sanction in the British Paramountcy had virtually

suffered dissolution with its withdrawal. The

Princely rulers genuinely believed that the States

were their fiefs and the British had usurped their

right to rule them. They visualised the end of the

British Empire as an act of deliverance for them,

which they believed would enable them to regain

the unquestioned authority they had as the

sovereigns of the states.

They considered accession of their States to India

as a new arrangement with the Dominion of India,

by virtue of which they would part with the

specific powers of the defence, foreign affairs

and communications of the states and retain the

rest of the powers of the governance without the

encumbrances the Paramountcy entailed.

Hari Singh had been shaken by Mountabatten's

advice to come to terms with Pakistan when the

Viceroy visited Srinagar. Accession to Pakistan

was the last act, Hari Singh was prepared to

perform. However, when he turned to India and

conveyed to the Indian leaders his desire to

accede to India the Indian leaders advised him not

to take any perceptible action in respect of the

accession, till the transfer of power had been

accomplished. The Indian leaders advised Hari

Singh to end the distrust with the National

Conference, release the leaders and cadres of the

Conference and take them into confidence and

commence preparations to associate them with the

government of the State.

After the transfer of power in August 1947 Hari

Singh promptly ordered fresh recruitment to his

armed forces and reportedly sought to secure field

guns from Patiala and Hyderabad. Reports appeared

in the newspapers in Pakistan that he tried to

seek military assistance from India and wanted the

Indian Government to take up the conversion of the

fair weather road from Jammu to Madhopur, into a

national roadway.

He was alarmed by the establishment of the

Provisional Government of Pak-occupied-Kashmir at

Tran Khel in the district of Mirpur by Sardar

Ibrahim Khan on 30 August 1947. Hari Singh knew

that the proclamation of the Provisional

Government of Azad Kashmir had been made in

connivance with the intelligence agencies of the

Government of Pakistan and the leaders of the

Muslim League to build pressure on him to accede

to Pakistan.

Meanwhile Sham Sunder Lal Dhar helped to bridge

the differences between Hari Singh and the

National Conference leaders. Hari Singh agreed to

revive the Dyarchy he had introduced in the State

Government in 1944, and provide a wider share of

power for the National Conference and accept to

entrust a fairly large measure of responsibility

in the State Government to National Conference

leaders as members of his Council of Ministers.

The National Conference leaders had shown their

readiness to join the State Government.

For Hari Singh however, the difficulties he faced

in regard to the accession were not eased. Several

developments in the process of the integration of

the States complicated his situation further.

Junagarh, situated in the midst of the Kathiawad

States, which had acceded to India, acceded to

Pakistan on the eve of the transfer of power. The

Nawab of Hyderabad refused to join India and

secretly plotted with the leadership of the Muslim

League to align himself with Pakistan.

Not only that. Mountbatten was at the helm of

affairs in India, where he had been placed by the

Congress leaders probably, to earn them a

favourable disposition of the British. Hari Singh

knew that Mountbatten had not forgiven him for his

audacity to send him back to the Indian capital,

without having agreed to abide by his advice to

come to terms with Pakistan. It is hardly possible

that the Congress leaders must not report have

received the intelligence of what transpired

between the Viceroy and the Maharaja in Srinagar.

But how did they install him the first

Governor-General of the Dominion of India is an

enigma, which continues to remain unexplained.

Hari Singh was unsure of the Congress leaders as

well, who had, in unabashed self-conceit,

indicated their willingness to accept a settlement

on the Princely States on the basis of their

population and geographical location. Perhaps,

they sought to use the influence of the Viceroy to

ensure the accession of the Muslim ruled States,

inhabited by Hindu majorities and situated within

the territorial limits earmarked for the Indian

Dominion to India. It is hardly possible that they

did not know the mind of the Viceroy and perhaps

the strategic implications of the future

disposition of Jammu and Kashmir to the British

interests in Asia. A section of the Congress

leadership was not averse to the division of the

States on the basis of their population even after

the transfer of power. Some of them believed that

Mountbatten would be able extricate Junagarh from

Pakistan and bring about the integration of

Hyderabad with India. Their prestige in the whole

of the Kathiawad peninsula had plummeted down as

they had reacted to the accession of Junagarh to

Pakistan pussiliminously. The rulers of the

Kathiawad States had to send Jam Sahib of

Nawanagar to convince the Congress leaders that

Junagarh posed a serious threat to them and to

demand immediate and effective action to liberate

Junagarh, which was fast slipping into a civil

wear.

The Congress leaders looked up to Mountbatten, who

advised them restraint. Later admissions made by

him in his interviews and memoirs, prove that he

was keen to secure the interests of Pakistan and

his country, Britain, in Jammu and Kashmir, but he

had no mandate from the British Government to

secure the Indian interests in the Muslim ruled

States of Junagarh and Hyderabad. He disapproved

of any perceptible action for the reclamation

Junagarh and Hyderabad.

Hari Singh did not lose sight of the problems,

arising out of his enemity with Mountabatten and

the duplicity of the Congress leaders. Jinnah

scuttled the proposals to divide the States on the

basis of their population and scoffed at the

suggestions made by Mountbatten. Hari Singh knew

that if he took a false step, Mountbatten as well

as the Congress leaders would nor hesitate to

abandon him in a bargain with Pakistan.

This was the greatest act of betrayal committed by

the men in power in India. The Indian Government

crumbled in its resolve to set right the wrong in

Junagarh and rein in the Nawab of Hyderabad. The

Indian leaders looked upto Mountbatten to deliver

them from their predicament though experience had

shown to them that the major role in the

integration of the States had been played by the

States people who had struggled for the unity of

the States with India and the Hindu rulers of the

States who had acceded to India.

The Government of India should have made a bold

move to take Hari Singh into confidence, thrash

out the issues pertaining to the transfer of power

to the peoples representatives with him and helped

in removing the prevailing distrust between him

and the National Conference leaders. Instead the

Indian leaders sulked away. Gandhi had advised

Hari Singh to handover the State Government to the

National Conference leaders and entrust them the

responsibility to conduct elections to the Praja

Sabha, the State Legislative Assembly and empower

the elected representatives of the people to take

a decision on the accession of the State. Hari

Singh had refused to abide by Gandhi’s advice and

told him that such a course would enable

Pakistan to grab the State with the support of the

Muslim Conference and the other pro-Pakistan

flanks in the state. Later events proved that Hari

Singh had chosen the right course. Jammu and

Kashmir would have gone the way, North West

Frontier Province did if he had opted for

elections to the Praja Sabha.

The Indian Princely States were a part of the

Indian nation. Partition did not divide the

States, nor did the partition empower Pakistan to

grab Junagarh or claim Hyderabad on the basis of

being Muslim ruled States and annex Jammu and

Kashmir on the basis of its population. The Muslim

League as well as the British treated the States

as their personal preserve and sought to use them

to Balkanise India. The Princes as well as the

people of the States defeated their designs.

The role played by Mountbatten and VP Menon, in

the integration of the Indian States was only

marginal. The States’ Ministry did not draw up any

plans for the consolidation of the northern

frontier of India of which Jammu and Kashmir was

the central spur. Nor did the States Ministry

formulate any plans for the security of the

Himalayas against the threat of their de-Sanskritsation

which the creation of Pakistan posed.

Few in-depth investigations

and inquiries have

been undertaken so far to unravel the forces and

factors, which shaped the events in Jammu and

Kashmir, during the fateful days following the

transfer of power in India. No investigations were

ever carried out in the actions of men, who were

at the helm of affairs in India, Pakistan and

Jammu and Kashmir, their motivations and their

personal prejudices. Much of what happened those

days, has been covered under false propaganda by

the Government of India as well as the Government

of Pakistan and the Interim Government which was

instituted in Jammu and Kashmir after the

accession of the State to India. A widespread

disinformation campaign was launched by the

Interim Government in collusion with the

Government to find scapegoats for their failures

and to apportion blame, where it did not belong.

The sordid story of what happened in the state,

those days, is yet to be told.

Pakistan sought to bend the procedure laid down by

the Indian Independence Act for the transfer of

power in India, to grab the Muslim majority states

as well as the states ruled by Muslim Princes.

The Indian Government failed signally to

counteract the stratagem, subversion and military

intervention, Pakistan employed to achieve its

objectives. Perhaps the British, who had quit

India, still cast a shadow on the Indian outlook.

The Congress leadership with its liberalist

tradition which denied the civilisational

boundaries of the Indian nation, continued to play

the Muslim card, to prove that Jammu and Kashmir

would be more Islamic than the Muslim State of

Pakistan after its inclusion in the Indian

Dominion.

The Congress leaders wanted Maharaja Hari Singh to

follow what they did in collusion with

Mountabatten to retrieve Junagarh and bring round

the Nawab of Hyderabad to come to terms, with

India. Gandhi advised Hari Singh, during his visit

to Kashmir, towards the close of July 1947, to (a)

transfer the powers of the State Government to the

representatives of his Muslim subjects, who formed

a majority of the population of the state; (b)

hold fresh elections to the Praja Sabha, the State

Legislative Assembly, on the basis of universal

adult franchise and (c) entrust the Praja Sabha

with the task of taking a decision on the

accession of the state. The meeting between Hari

Singh and Mahatma Gandhi was held on the lawns of

the Gupkar Palace, situated on the eastern bank of

the Dal Lake in Srinagar. Maharani Tara Devi and

the Heir-Apparent Karan Singh were present in the

meeting. The only other man present in the meeting

was a senior officer of the state army, who acted

as an aide to the Maharaja and prepared the

situation report of the meeting for the military

archives of the state.

Gandhi had lost touch with the developments in the

princely states. He was not aware of the

dangerous situation in Jammu and Kashmir. He did

not know that an armed rebellion was brewing in

the Muslim majority districts of the Jammu

province, where arms and ammunition were being

dumped by the elements of the Muslim League from

a cross the border of the state with the Punjab.

He was hardly aware of the sharp divide between

the Kashmiri speaking Muslims and non-Kashmiri

speaking Muslims. He did not know that the

non-Kashmiri speaking Muslims, who constituted

nearly half the Muslim population of state along

with a small section of the Kashmiri-speaking

Muslims owing loyality to the Mirwaiz, the chief

Muslim divine of Kashmir, supported the Muslim

Conference, which spearheaded the struggle for

Pakistan. He was completely unaware of the fact

that the Kashmiri-speaking Muslims constituted

about half the population of the Muslims of the

State and together with the Hindus, the Sikhs and

the Buddhists they formed more than sixty percent

of the population of the State. The Hindus, the

Sikhs and the Buddhists, a million people,

constituted more than a quarter of the population

of the State. Gandhi was completely unaware of the

impact of the partition on the leaders and cadres

of the National Conference, which had its main

support bases in the community of the

Kashmiri-speaking Muslims, largely concentrated in

the Kashmir province. He did not know that an

influential section of the leaders and cadres of

the National Conference favoured a reconsideration

of the commitment of the National Conference to

the unity of India.

Gandhi believed that by seeking to divest Hari

Singh of his powers to determine the future

affiliation of the State in respect of its

accession and empowering his Muslim subjects to

take a decision on the accession of the state, he

would be able to create a precedent for the rulers

of the Muslim ruled states, to entrust their

powers to determine the future affiliations of

their states their Hindu subjects, who formed a

majority of their population. Nearly all the

Muslim ruled states, barring a few of them

situated within the territories delimited for the

Muslim State of Pakistan, nearly all the Muslim

ruled States in India, including the major states

of Hyderabad, Junagarh, Bhopal, were populated by

preponderant Hindu majorities.

Perhaps, Gandhi believed that the Muslims of Jammu

and Kashmir committed to support the accession of

the state to India, would opt to join India after

power was transferred to them and they were

empowered to determine the future affiliations of

the state. He was convinced that the transfer of

power in Jammu and Kashmir would provide him a

moral ground to bring round Pakistan as well as

Mountbatten to persuade the Muslim rulers to

abnegate from their power to determine the future

affiliations of their states and entrust their

subjects and of whom the Hindus formed a majority,

to opt for India.

Gandhi and the other Indian leaders did not even

get the wind of the secret preparations in

Pakistan for military intervention in the Jammu

and Kashmir State in the name of the Jehad for the

liberation of the Muslims from their subjection to

the Dogra Rule, while Gandhi went on a indefinite

fast to prevent communal violence in India which

threatened the Muslims, Pakistan prepared

feverishly for the invasion of the state. Pakistan

planned to reduce the state by military force and

then deal with India from a position of strength

in respect of Junagarh and Hyderabad. Junagarh had

acceded to Pakistan and Hyderabad was plotting the

align itself with Pakistan to remain out of India.

Had Hari Singh accepted Gandhi's advice he would

have provided open ground for Pakistan and the

Muslim League to grab the state by stratagem and

force.

Gandhi's suggestion to hold the elections to the

Praja Sabha would have enabled the Muslim

Conference and the flanks of pro-Pakistan Muslim

activists, operating underground, to sabotage the

National Conference and use religious appeal for

Jehad to pack the Praja Sabha with the Muslim

Conference. Any stringent measures adopted by him

to prohibit religious propaganda in the elections

would have brought him the blame of having settled

the expression for the will of the Muslims. In

case he did not take effective measures to

prohibit the use of religious propaganda in the

elections he would virtually leave the field open

for the Muslim Jehad to take over.

Hari Singh had borne the ravages of Muslim

communalism. He had also faced the scourage of the

Paramountcy. The Congress leaders had installed

Mountbatten as the first Governor General of the

Dominion of India. Hari Singh had rebuffed

Mountbatten and refused to abide by his advice to

join Pakistan. Mountbatten, later events proved,

had not forgotten the slight Hari Singh had caused

to him. The Maharaja did not allow himself to be

arranged before the man, who had spared no efforts

to push his state into Pakistan for his

management. He refused to accept Gandhi's advice.

Hari Singh contested Gandhi's views on the

accession of the state and refused to abnegate

from his rightful obligation to determine the

future of his state. He told Gandhi, in measured

words in the presence of Maharani Tara Devi, who

regarded the Mahatma in awe, that the safety and

the security of the Hindus and the other

minorities in the state was uppermost in his mind,

and he would not abandon them at any cost. He

insisted upon the recognition of his rights as the

ruler of the state to determine the basis of his

future relations with India. He reminded Gandhi

that nor only had the lapse of the Paramountcy

vested in him the right to determine the future of

the State, the Indian States Ministry had

recognised the rights of the rulers of the States

as the basis of their accession to India and he

could not be treated in a manner different from

the way, the rulers of all other acceding states

had been treated.

Gandhi gave expression to his feelings in a

statement he gave to the press in Punjab, on his

way back to Delhi. He said that Jammu and Kashmir

was a Muslim state and therefore, its future must

be determined by Muslims who formed a majority of

its population. He denounced the treaties between

the Princes and the British as "parchments of

paper" and decried the claims made by the Princes

to any rights arising out of such treaties.

Hari Singh did not accept the surrender to a

Muslim majority identity as the basis of a

settlement of the accession of the state. He

refused to become part of the process to

consolidate the borders of the Muslim state of

Pakistan, which Mountbatten and the Congress

leaders visualised as the guarantee of the unity

of India.

Later events proved Hari Singh right. Pakistan

strove hard to hold Junagarh and openly supported

Hyderabad in its endeavour to remain out of India.

Pakistan invaded the State, irrespective of the

procedure laid down by the Indian Independence

Act, for the lapse of the Paramountcy, showing

little regard for the ruler of Jammu and Kashmir

and the people of Junagarh and Hyderabad.

Gandhi’s press statement administered a jolt to

Maharaja Hari Singh. Maharani Tara Devi favoured

reconciliation with the Congress leadership. She

cautioned Hari Singh against the isolation into

which the State was sinking fast. It is a lesser

known fact that the Maharani tried to bridge the

gulf between Hari Singh and the Indian leaders.

Shortly after Gandhi left Kashmir Hari Singh

removed Ram Chandra Kak from his office and

appointed General Janak Singh, one of his close

kin the Prime Minister of the state. Ram Chandra

Kak headed the State Government during the last

years of the British Raj in India. Kak served the

Maharaja with unflinching loyalty and devotion.

Kak belonged to the Kashmiri Pandit community in

Kashmir, which played a pioneering role in the

growth of national consciousness in the State.

While in office, Kak acted as an interface for the

Maharaja with the British as well the Muslim

League, at a time, when the Princes were

struggling to place the State in between the

British Crown and an independent Indian nation.

The political Department of the British Govt. of

India, with conrad corfield, a diehard British

Civil Service officer, as its head, spared no

efforts to assure the Princes that the British

would not abandon the Princely India and would

ensure the continuity of the treaties between the

States and the Crown. Like the other Princes, Hari

Singh was suddenly brought on the crossroads, when

India was divided and the British Paramountcy was

withdrawn.

The British refused to continue the protection,

the Paramountcy had provided the States and the

Muslim League claimed Jammu and Kashmir for the

Muslim State of Pakistan on the basis of the

Muslim majority of its population.

During the days, the future of the constitutional

organization of India was taking shape, Ram

Chandra Kak was at the Centrestage of the

negotiations between the Princes, the British and

the Indian leaders. The Princes were not left with

the choice to seek a place outside the

constitutional organization of the two successor

Dominions of India and Pakistan. The

undersecretary of the State for India in the

British Government, clarified in the British

Parliament, during the debate on the Indian

Independence Bill, that the British Government

would not recognize the States as the Dominions of

the Commonwealth nor would extend it recognition

to their independence. Kak was no longer relevant

in the political context in which Jammu and

Kashmir was left with no choice except to join

India, the option to accede to Pakistan was not

acceptable to Hari Singh or Kak.

Hari Singh turned away from the British, when he

refused to abide by the advice of the Viceroy of

India tendered to him to come to terms with

Pakistan.

He earned the displeasure of the leaders of the

Muslim League, when he refused to grant permission

to Mohammad Ali Jinnah to visit Jammu and Kashmir,

during the days, the transfer of power in India

was in process of completion. Jinnah sent several

of his emissaries to persuade Hari Singh to accede

to Pakistan on conditions which he specified. A

second world war veteran Major General Shaukat

Hayat Khan, arrived in Kashmir with a peculiar

proposal from him.

Khan met Hari Singh in his palace. He told the

Maharaja that he had been commissioned by Jinnah

to convey to the Maharaja that he could lay down

any conditions that he chose, to accede to

Pakistan and that Pakistan would deposit a huge

amount of money in British currency worth hundreds

of millions of Sterling Pounds, in the Bank of

England, as guarantee against any breach of the

conditions laid down by him.

Hari Singh was slighted, but he did not lose his

poise. He told Shaukat Hayat that he would take a