Jammu and Kashmir: The issue

of Accession

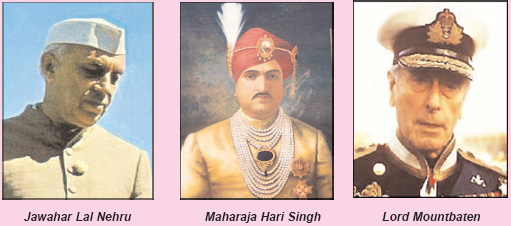

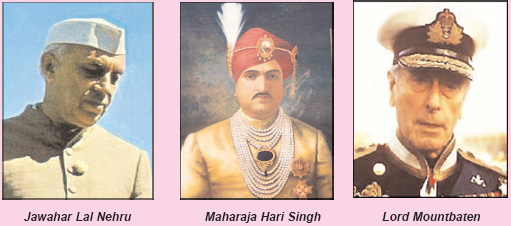

By Dr. M.K. Teng

November 2010

Distortion of the history of the partition of

India, false propaganda and lies, shroud the

accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India in 1947,

as well as the exclusion of the State from the

Indian Constitutional organization by virtue of

Article370 of the Indian Constitution in 1950. The

Indian political class in its attempt to

substitute “greater autonomy “of the State, for

the “right of self-determination” , Pakistan and

the Muslim separatist forces have been demanding

during the last six decades, has undermined the

national consensus on the unity of India and the

secular Integration of the people of the State and

people of India on the basis of the general right

to equality.

Today the whole nation is

confronted with a situation which threatens to

disrupt the unity of the country and endanger its

territorial integrity. The people of India need to

stand up as one man to expose the perfidy which

has virtually pushed the State of Jammu and

Kashmir to the brink of disaster. Nearly half of

the State is under the occupation of Pakistan. To

allow the reorganization of the other half into a

separate sphere of Muslim power, will eventually

pave the way for the disintegration of the

civilisational boundaries of the Indian State.

Partition and the States

The creation of two Dominions

of India and Pakistan was restricted to the

division of the British India and the separation

of the British Indian provinces of Sind,

Baluchistan, North-west Frontier Province, the

Muslim majority contiguous regions of the province

of the Punjab, the Muslim majority eastern region

of the province of Bengal along with the Muslim

majority regions of the Hindu majority province of

Assam. The princely States, which formed an

integral part of the British Indian Empire, were

not brought within the scope of the partition

plan.

The process of the transfer

of power envisaged the lapse of Paramountacy, the

authority the British Crown exercised over the

States, liberating them from the British imperial

authority. The lapse of the Paramountacy

underlined the reversion of the powers, which the

British exercised in respect of the princely

States, to their rulers who were required, in

accordance with the transfer of power, to accede

to either of the two dominions or come to such

agreements with them as they deemed fit. The

British as well as the Muslim League insisted upon

the lapse of the Paramountacy and the reversion of

the powers to determine the future of the States,

to their rulers. Both the British as well as

Muslim league stubbornly opposed the proposals

made by the Indian National Congress to empower

the people of the States to determine the future

disposition of their States in respect of their

accession.

It is important to note that

the States formed an integral part of the British

Empire in India and were never recognized as

independent entities by the British during their

rule over India. The lapse of the Paramountacy

did not imply the independence of the States. This

was made expressly clear by British

under-Secretary of State for India, during the

debate on the Indian Independence Bill in the

British Parliament, when he categorically stated

that the British Government would neither accord

the status of Dominions to any princely State nor

recognize its independence. In fact, the truth is

that while negotiations on the partition plan were

in progress, the British officials assured Nehru

and the other Indian leaders that if the partition

plan was accepted, the Hindu majority provinces

and regions of the British India as well as the

princely States would be united in the Dominion of

India.

The Indian Independence Act

did not lay down any provisions in respect of the

procedure for the accession of the princely States

to the two dominions and the terms on which the

accession would be accomplished. After the 3 June

Declaration the States Department of the

Government of India was divided into two sections:

the Indian Section which was placed under Sardar

Patel and the Pakistan Section which was placed

under Sardar Abdur Rab Nishtar of the Muslim

League. The task of laying down the procedure of

the accession of the States to India was entrusted

to the Indian Section and the task of laying down

the procedure for accession of the States to

Pakistan was entrusted to the Pakistan Section.

The Indian Section drew up an Instrument of

Accession for the accession of States to India. So

did the Pakistan Section for the accession of

States to Pakistan. The Instrument of Accession

enshrined the procedure and the terms in

accordance with which the rulers acceded to either

of the two Dominions. The Instrument of Accession

drawn up by the Indian Section laid down two sets

f terms and procedures, one for the larger

princely States and the other for the smaller

princely States. It is important to note here that

the States were provided no option, except to

accede to India on the terms and conditions laid

down by Indian Section or to accede to Pakistan on

the terms and conditions laid down by the

Pakistani Section of the Indian States Department.

All the larger princely States which acceded to

India, including Jammu and Kashmir, signed the

same standard form of the Instrument of Accession

and accepted the terms it enshrined.

The Instrument of Accession

enshrined acceptance by the rulers of princely

States to unite their domains with the Dominion of

India on terms and conditions and in accordance

with the procedure laid down by it. It has been

already noted here that princely States were never

recognized by the British as independent entities.

They formed a subsidiary structure of the British

colonial organization of India which was subject

to the British Crown. The lapse of Paramountacy

did not alter their status. Yes, the dissolution

of the Paramountacy opened the way for them to

stake claim to independence. Several of the

princely States in fact did stake their claim for

independence. When the British refused to

recognize the independence of the States, the

Nawab of Bhopal, who was then the Chancellor of

the Chamber of Princes approached the American

Diplomatic Mission in India to solicit support for

the independence of the States. The American

Mission promptly turned down the request of the

Nawab. That left no option for the Nawab to accept

to accede to India, which he did without any loss

of time. The ruler of Jammu and Kashmir was not

among the rulers, who staked claim for

independence of his State.

The Instrument of Accession

signed by the rulers of the princely States,

including Jammu and Kashmir, stipulated the

unification of the States with the two successor

States of the British Empire in India. The

transfer of power in India underlined the creation

of only two successor States of the British Indian

Empire: the Dominion of India and the Dominion of

Pakistan. The lapse of the Paramountacy put the

States on the inevitable course which led them to

accede to either of the two successor States.

The rulers located within the

geographical boundaries of the Dominion of

Pakistan, acceded to Pakistan. The ruler of Kalat,

who was opposed to the accession of Kalat to the

Dominion of Pakistan, was smothered into

submission by the Muslim League with the active

support of the British. All the other princely

States were situated in the geographical

boundaries earmarked for the Dominion of India.

The State of Jammu and Kashmir was contiguous with

both India and Pakistan. Its borders stretched

along the boundaries of the Dominion of Pakistan

in the West and the South-west, while its borders

in the East and the South-east rimmed the

frontiers of the Dominion of India. The ruler of

Jammu and Kashmir, Maharaja Hari Singh harbored no

illusions about the accession of his State to

Pakistan and eagerly awaited a clearance from the

Congress leaders, who had secretly advised him not

to take any precipitate action in respect of the

accession of his State, till Hyderabad and

Junagarh were retrieved. He himself was aware of

the dangers of any wrong step on his part, which

he knew would lead to a chain reaction in the

States ruled by the Muslim rulers. He did not want

his State to be used as a pawn by Pakistan.

Pakistan had no special

claim to Jammu and Kashmir on the basis of the

Muslim majority composition of its population. As

already mentioned here the Muslim League strongly

opposed any suggestion to recognize the right of

the people of the princely States to determine the

future of the States. It was only when Pakistan

failed to grab Jammu and Kashmir after it invaded

the State in October 1947, and the Indian military

action frustrated its designs to swallow Hyderabad

and Junagarh, both the States located deep inside

India, that Pakistan raised the bogey of

self-determination of the Muslims of the State of

Jammu and Kashmir on the basis of their numerical

majority.

Accession

The Instrument of Accession

was executed by the ruler of Jammu and Kashmir

State on the terms specified by the Dominion of

India. Neither the ruler of the State, Maharaja

Hari Singh, nor the National Conference leaders

played any role in the determination of the terms,

the Instrument of Accession underlined. Sheikh

Mohammad Abdullah and many National conference

leaders were in jail when the transfer of power in

India was accomplished by the British. Sheikh

Mohammad Abdullah was released from Jail on 29

September 1947, about a month and a half after the

British had left India. Three days after his

release the Working Committee of the National

Conference met under his presidentship and took

the decision to support the accession of the State

to India. The decision of Working Committee was

conveyed to Nehru by Dwarka Nath Kachroo, the

Secretary General of the All India States Peoples’

Conference, who was invited to attend the Working

Committee meeting of the National Conference as an

observer. Kachroo was a Kashmiri Pandit who had

steered the movement of the All India States

Peoples’ Conference during the fateful days in

1946-1947, when partition and the transfer of

power in India were on the anvil.

Interestingly the National

Conference leadership kept the decisions of the

Working Committee as a closely guarded secret.

Within a few days after the Working Committee

meeting, the National Conference leaders sent

secret emissaries to Mohammad Ali Jinnah and the

other Muslim League leaders. While Sheikh Mohammad

Abdullah held talks with a number of Muslim League

leaders of the Punjab, who had come to Srinagar

after his release, he sent two of the senior most

leaders of the National Conference, Bakshi Ghulam

Mohammad and Ghulam Mohammad Sadiq, to Pakistan to

open talks with the Muslim League leaders. Jinnah

spurned the offer of reconciliation the National

Conference leaders made and refused to meet the

National Conference emissaries. Ghulam Mohammad

Sadiq was still in Pakistan when Pakistan invaded

the State during the early hours of 22 October

1947.

While the invading army

spread across the State Hari Singh sent his Prime

Minister, Mehar Chand Mahajan to Delhi to seek

help to save his State from the invasion and

offered accession of the State with India. Sheikh

Mohammad Abdullah had already reached Delhi. He

made no secret of the danger the State faced and

asked Nehru to lose no time in accepting the

accession and ensuring the speedy dispatch of the

Indian troops to the State. The instrument of

Accession was taken to Jammu by V. P. Menon, where

it was signed by the Maharaja. Menon then rushed

back to Delhi and got the Instrument Accepted by

Mountbatten. Next day, the air-borne troops of the

Indian Army, reached Srinagar.

Hari Singh laid no conditions

for the accession of the State to India. The

National Conference leaders were nowhere near the

process of the Accession of the State, to lay down

any condition for the accession of the State to

India. The Congress leaders including Nehru made

no promises to the National Conference leaders.

The terms of the Instrument of Accession were not

altered in any respect by the Viceroy. Nehru,

Patel or any other Congress leader gave no

assurance to the Conference leaders about autonomy

or Special Status of the State. In fact the

National Conference leaders did not make any such

demands at any time, while the process of the

accession was in progress.

The National conference

leaders demanded the exclusion of Jammu and

Kashmir from the Indian constitutional

organization in the summer of 1949, when the

Constituent Assembly of India was in the midst of

framing the Constitution of India. This was the

time when the foreign power intervention in Jammu

and Kashmir had just begun to have its effect on

the deliberations of the Security Council as well

as the developments in the State.

Legal platitudes apart, the

letter written by Mountbatten to Hari Singh

suggesting to elicit the opinion of his people,

did not prejudice the stipulations of the

Instrument of Accession. The Governor General of

India did not have the power to alter the

stipulations of the Instrument of Accession, nor

did Nehru, the Prime Minister of the Interim

Government of India, have any powers to make any

alterations.

The Instrument of Accession

was an act performed by the ruler of Jammu and

Kashmir to unite his domains with the State of

India. Mountbatten, in the capacity of the Crown

Prince as well as in the capacity of the Governor

General of India, had only one power to exercise:

to accept the Instrument of Accession, executed by

the ruler of Jammu and Kashmir. The fact is that

as the Crown Prince and the Governor General of

the Indian Dominion, he exercised powers vested in

him by the Indian Independence Act, which were

strictly limited to his acceptance of the

accession of Jammu and Kashmir, Hari Singh

offered. It is important to note that Mountbatten

could not refuse to accept the Accession of Jammu

and Kashmir to India. Indeed he had no powers to

refuse to accept the Accession of any other State

to India. So much so that he did not refuse to

accept the accession of Junagarh to India, which

was accomplished in a political crisis, the

rebellion of the people of the State against the

ruler led to.

Moreover Mountbatten did not

write the covering letter to Maharaja, because the

National Conference leaders had laid down any

condition to that effect, or because composition

of the population of the State of Jammu and

Kashmir was dominantly Muslim. Both Mountbatten’s

letter and Nehru’s commitment to elicit the

opinion of the people of Jammu and Kashmir, was in

continuation of the commitments the Congress

rulers had made to rulers and the people of

Hyderabad and Junagarh.

Nawab of Hyderabad was trying

frantically to align his State to Pakistan against

the wishes of his people. Hyderabad was situated

deep inside the Indian mainland, south of the

Vindhyas and Junagarh was situated in the midst of

Kathiawad States which had acceded to India. The

accession of Junagarh to Pakistan and the

insistence of the Nawab of Hyderabad threatened to

disrupt the unity of India and balkanize it. Nehru

as well as Patel pleaded with the Nawab of

Hyderabad to ascertain the wishes of his people in

respect of the accession of his State. Nehru as

well as Mountbatten repeatedly requested the

leaders of Pakistan to agree to refer the

accession of Junagarh to Pakistan, to the people

of the State. While Mehar Chand Mahajan was

pleading with Nehru to accept the accession

offered by Hari Singh, Junagarh was in a state of

civil war and Nawab of Hyderabad was secretly

plotting with Pakistan the course of action he

would take after Hari Singh had acceded with

India. Nehru sought to reinforce his interests in

Hyderabad and Junagarh by repeating the offer of

eliciting the opinion of the people of Jammu and

Kashmir in respect of their accession.

The Instrument of Accession

was a political instrument and the accession of

Jammu and Kashmir was a political act, which had

international implications for it formed a part of

the process of the creation of the state of India.

As such the Instrument of Accession, executed by

Maharaja Hari Singh, was irreversible and

irreducible, irrespective of the circumstances and

events in which it was accomplished.

The Indian princely States

were not required to execute any Instrument of

Merger. The claim made by some quarters in Jammu

and Kashmir that the State had not signed the

Instrument of Merger, which such quarters insist,

saved Jammu and Kashmir from being integrated in

the constitutional organization of India, is a

travesty of History. The State Department of India

laid down a procedure for the integration of

smaller princely States into administratively more

viable Unions of States. To complete the procedure

of integration of the small princely States into

the Unions of States, The State Department drew up

an Instrument of Attachment, erroneously described

as Instrument of Merger. The major Indian States,

including Jammu and Kashmir were not required to

sign the Instrument of Attachment. Also Instrument

of Accession had no bearing on the integration of

the States into the Indian Constitutional

Organization.

The withdrawal of the

invading army of Pakistan from territories of the

State under its occupation was the precedent

condition, laid down by Mountbatten, Nehru and the

Security Council for any reference to the people

of Jammu and Kashmir State. Pakistan refused to

withdraw its forces from the occupied territories

of the State. It has so far distorted the

discourse of the accession of the State to suit

its denial.

(Dr Mohan Krishen Teng

is a retired Head of Department of Political

science of Kashmir University. He has written

extensively on the constitutional and political

history of Jammu and Kashmir. His seminal works on

Article 370, Special Status, and government and

politics in Jammu and Kashmir have been

internationally acclaimed.)

Source: Kashmir

Sentinel

|

No one has commented yet. Be the first!