The

Bhand Pather of Kashmir

(A dramatic from based on mythological stories

incorporating contemporary social satire within its practical theme).

While I was doing

a workshop with some Bhands in Kashmir I met Ama Kak, an elderly

man, a master at his art. In the evenings he would take me up a hillside

and we would sit there watching the lush green valley slowly clothe itself

in darkness. He would play his swarnai, unfolding one mukam

after another. The surroundings echoed with the sound of his music in its

intricate patterns. Often he would stop and say, "who wants these things

now. It will all soon die out and no one will ever know that we the Bhands

had such a rich and developed phun, heritage."

The village of Akingam in the Anantnag district

of Kashmir, 45 kilometers from Srinagar is the home of a community of Bhands,

the traditional performers of the valley. Spread over a number of villages

at the foothills of an endless mountain range, these people move from place

to place with their extensive repertoire. A short distance up one of the

smaller hills in this area sits a famous temple dedicated to the goddess

Shiva Bhagvati. Once a year, in honour of this goddess, the

Bhands

who are Muslims, perform a special ritualistic dance known as the chhok

done with great devotion and faith. During this time the temple in enveloped

in an atmosphere charged with a sense of timelessness, a cosmic reality.

An extremely superstitious people, the Bhands perform this particular

chhok at this temple and nowhere else. However, other shows are

presented elsewhere, at Muslim shrines as well as at Sufi centres.

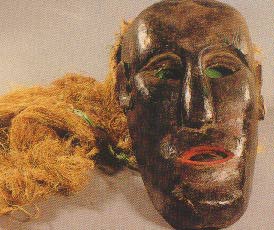

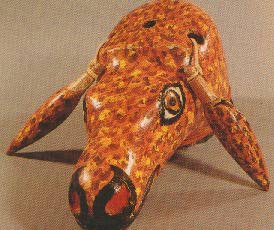

Masks used in Bhand Pather

The secular outlook of Bhands is reflected

in their dynamic folk form that has incorporated many elements from the

classical Sanskrit theatre as well as from other traditional folk forms

of India. But over the years many aspects have been lost and others have

undergone dramatic changes.

The plays of the Bhands are called pather,

a word that seems to have derived from patra, dramatic character. Bhand

comes from the bhaana, a satirical and realistic drama, generally

a monologue that is mentioned in Bharata's

Natya Shastra. The Bhand

Pather though is not a monologue but a social drama incorporating mythological

legends and contemporary social satire. Born Hindus, the Bhands

converted to Islam and remain very secular in their outlook. An extremely

simple, witty and practical people. The

Bhand Pather unfortunately

does not sustain them economically and they have been driven to other professions

primarily weaving the basket work of the kangris, wolloen blankets and

carpets.

Post tenth century onwards has been a time when

there were foreign invasions in the valley, the social fibre was disturbed

and the Kashmiri became a slave in his own land where he had to face and

live with alien cultures, religious and socio- political systems. This

cross exchange also come through in the folk tradition of the state. The

injustice that the people suffered was expressed in the plays albeit as

absurd or humourous be it the king in Darza Pather or the royal

soldiers in Shikargah, who speak in Persian to the poor and illiterate

Kashmiri and expect him to understand a foreign tongue and whip him for

not replying. Or the English couple in Angrez Pather who speak a

hilarious version of the language to a resthouse guard while out on a hunt.

In the Gosain Pather which is about Shiva and the Saivites of Kashmir,

large puppets with masks are used to project the sense of oppression through

the characters of the king or the witch. In all the plays, the local character

is the protaganist, victorious in the end.

The tradition and form is handed down through

the generations from father to son. The Bhand has to train himself

to be a skillful actor, dancer, acrobat and musician. The leader of the

troupe is called the magun, a word taken from

maha guni,

a man of varied talent. He teaches his people the art and expertise of

their inheritance. Today the training is virtually non-existent. A danger

signal of the impending doom on this form of entertainment. The finest

performers all belong to the older generation.

Acting, dance and music are an integral part of

the form as a whole. In pure tradition, the performances begin in the evening

with a ritualistic dance, also called a chhok but different from

the one done at the Shiva Bhagvati temple. With the onset of night the

play unfolds gradually and ends in the early hours of the morning with

the magun doing a duay kher, a prayer or blessing.

The Bhands dance to the tune of a specified

mukam

and the orcehstra includes the

swarnai,

dhol, nagara and

the thalij. The swarnai is larger in size than the shehnai

with a strong and metallic sound that has arresting impact in the open

air arena. This instrument attracts audiences from the vicinity. A very

special wind instrument, it is made in three parts: the

nai or wooden

pipe made by special carpenters, the barg, a reed of a particular

grass found locally and a copper disc the diameter of the pipe into which

the barg is fitted. Before the

swarnai player adopts his newly made

instrument a ritual offering is made in dargah. The composition played

is called a mukam and each

Bhand Pather has its own. The

music follows a set pattern, the salaam, thurau, dubitch, nau patti

and the salgah. There is a highly developed system of music based

on the classical mould of the

sufiyana kalaam with intricate and

codified patterns.

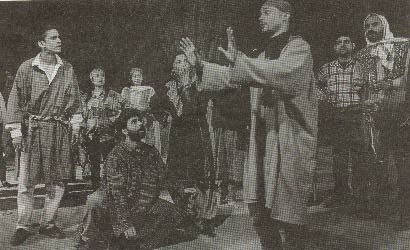

Scenes from Bhaand

pather

The man who plays the

dhol is the central

figure in the orchestra. Many taals in various combinations are played

on this drum but unfortunately today very few remain. The nagara

is an ascompaniment to the dhol and the rhythm doubles in intensity

as the play proceeds. More than one nagara is used in the performance

to emphasize the sound of the instrument. The

thalij is a metal

cymbal a little larger than those used in other musical forms. To this

music are added Kashmiri folk songs, sung throughout the play.

The two properties that are a must for every

pather

are a whip and a short bamboo stick. The

koodar, or long whip is

crafted from the dry stem of the bhang plant and looks like a thick rope

which is forked at its tip. When used it emanates a sound similar to a

gunshot. During the performance a character can be whipped a hundred times

without being hurt because this property does not have the impact associated

with a whip, it just looks deadly. It is used to transform all the elements

that represent oppression into strong dramatic images. In sharp contrast

the bans are used by the jester or maskhara. These are split bamboo

sticks that make a sharp sound. In his pantomime, the maskhara uses

the bans emerges as the total opposite of the oppressors whip.

The kaper chadar or sheet of cloth is used

as a curtain. Some of the actors make their entrance from behind this chadar.

The same cloth is often used as a canopy for the king when he holds court

is some other scene. The use of the kaper chadar is reminiscent

of the yavanika described in the

Natya Shastra and which

is also used in Kathakali and Yakshagana.

The Maskharas are one of the most important

characters in the Bhand Pather. They lampoon the king and the upper

classes by exposing their corruption. The jester is the constant factor

in the performance, the link of the various episodes. The elements of homour,

be it hazal (mockery),

mazaak (jokes), tasan (sarcasm)

or even finding fault with the other characters is the forte of the

maskhara.

They do very accurate caricatures of society using a great deal of pantomime.

Finally, the maskhara emerges as the rebel, the character who does

not cow down to the oppressor. The message that comes across through the

performance the message of the political and social scene, makes the Bhand

Pather a very relevant and contemporary traditional folk form - a political

and social review.

Performances take place in the open air and there

are no clearly defined acting areas. The actors can move about climb the

roof of a house or even a tree if they so choose. In the Watal Pather

a satirical play about the profession of sweepers who in Kashmir are not

considered untouchables, a wedding procession that is part of the action

comes through the village drawing crowds along with it and ends up at the

point where another episode of the performance has already begun. This

simultaneous action is an interesting aspect and is done in other patheras

well. Another example is a king may be seen holding court at one point

and farmers are ploughing the field at another. These instant juxtapositions

give another very subtle and sensitive dimension to this form.

The predominant language used is Kashmiri but

there is also a use of Gujjari, Punjabi, Dogri, Persain and sometimes even

English, Non- Kashmiri words are used to accentuate the humourous and absurd

situations to create dramatic effects and totally incongrous expressions.

The style of acting swings from the purely realistic

to the highly exaggerated. The pantomime achieves an abstract, graphic

quality making it a strong element in the fabric of the Bhand Pather.

A good example is from the Arim Pather or the vegetable gardeners'

pather rarely done today, where the

maskhara as the gardener

carries a teeshaped wooden contraption on which is tied a rope and an earthern

pot. He mimes putting the pot into an imaginary well and draws the water

to water his vegetables. Later the same pot becomes the well and he talks

to a ghost that lives within it. Eventually, frustrated that the owner

of the garden will not permit him to marry his daughter he breaks the pot

and runs away.

The narrative of this form moves fairly rapidly

from episode to episode with no elements of suspense. It is epic in its

quality and the audience knows the action well. They know what is to come

but do not know how the event will happen. Though the story line revolves

around old stories of kings and their times the message projected is loaded

with contemporary statements. All the performances end with the recitation

of the duay kher, praying for the betterment of the land and people protecting

them from disease and death. Very auspicious, the duay kher is spoken

by the

magun and repeated by the audience.

The Bhands are found in almost all of the

districts of Kashmir and performances are a regular feature of life there.

Some of the pathers have died, other are becoming rare, the form

takes on new elements and continues to survive but alas precariously. The

music has changed and unfortunately the traditional

mukams, ragas

are not played as much.

The Bhands in their day to day living reflect

their firm belief, in the faith of a unique fusion of Kashmiri Shaivism

and Sufi traditions of the valley.

|