Homeland

after Eighteen Years: A 48 hour Travelogue in

Kashmir

BOOK REVIEW

by Prof. K B Razdan (Phd. Ex- Prof of

English

Jammu

University)

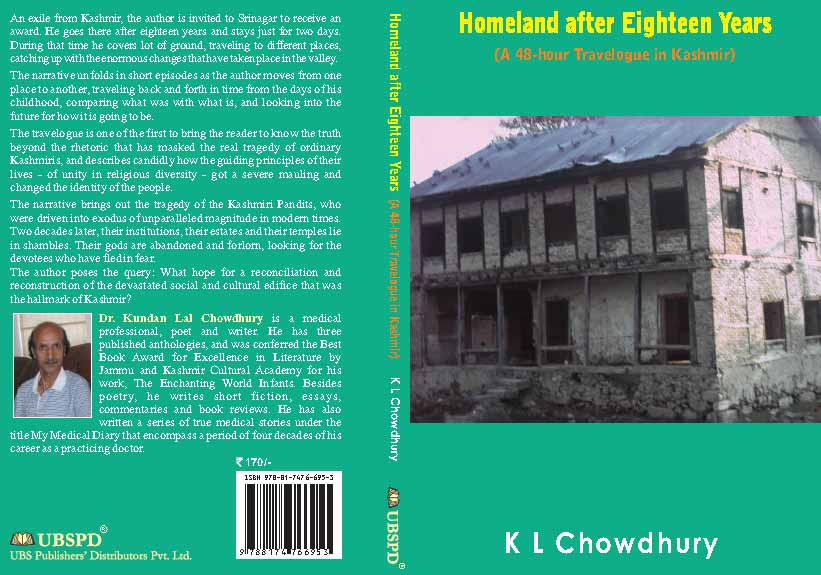

Name

of the book: Homeland

after Eighteen Years: A 48 hour Travelogue in

Kashmir

.

Author:

K L Chowdhury

Publisher:

UBS Publishers Distributors Pvt. Ltd.

New Delhi

Year

of Publication: 2011.

Price:

Rs.170/-

Dr. K L Chowdhury’s poetic travelogue,

narrating his 48 hours stay in Srinagar and its

environs, in early October 2008, constitutes a

significant first-person singular narrative of the

author’s experiences and perceptions when he

went there to receive the ‘Lifetime Award for

the Best Book in English’ for his anthology

“Enchanting World of Infants” (2008), from the

J&K Academy of arts, Culture and

Languages.

Going

back to

Kashmir

“after eighteen years”, “nearly a

generation”, the author explains in the

“Introduction”, “was a hard decision to

make”. After “having been violently thrown

out”, as he says, going back would be “a

painful proposition”. Yet, the irresistible pull

to visit the homeland after nearly two decades,

proves eventually impossible to ignore. A

“burning desire” to go up the Shankaracharaya

hill and visit the Shiva temple at the top, along

with the magnetic tug of Rajveri Kadal in downtown

Srinagar

, his birth place “to walk the lanes, where i

spent my childhood,” become catalytic factors

which conquer Chowdhury’s initial doubts before

he decides to go and give it a try.

The

travelogue, opening with the first poem on

3 October 2008

“On Board Jet Airways, Jammu-Srinagar”,

develops into a gripping narrative in the annals

of diasporic literature. The reader finds it

virtually impossible to put down the volume, once

he or she starts to read it. Chowdhury, thanks to

his racy poetic profundity and rapidity, makes the

reader accompany him all through his journey till

his return flight on 5 October.

His deceased friend’s son, Rauf, drives

him to diverse places before the Award receiving

ceremony, and the author acknowledges that “With

young people like him, there is hope for

Kashmir

”.

Rauf’s

car becomes the contemporary Noah’s Ark, taking

the author to all those localities of Srinagar

city which remain still dear to him, churning

memories, associations, and ties, hanging like

finest silken threads in the innermost chamber of

his consciousness, and exposing the tragedy of an

ethnic minority, the Kashmiri Pandits, who were

“driven into exodus of unparalleled magnitude in

modern times”. As the narrative “unfolds in

short episodes”, when the author moves from one

place to another, the reader comes to know about

“the truth beyond the rhetoric that has marked

the real tragedy of ordinary Kashmiris”. A

climactic query is posed: “What hope for a

reconciliation and reconstruction of the

devastated social and cultural edifice that was

the hallmark of

Kashmir

?” Two decades after the outbreak of

secessionist insurgency in

Kashmir

, the author feels that though “terrorism has

beaten a retreat for some time, and threats to

life receded, yet the consolidation of an

aggressive religious mind-set and a relentless

trend to cultural and religious exclusivity”,

still pose problems and challenges.

“Homeland

after Eighteen Years” also serves as an

arresting, poetic compendium of historicism which

projects the author into the past, an investigated

past which functions as a historical agent.

Chowdhury - the doctor in real life that he is -

dissects, anatomizes, and eventually diagnoses,

the ills, afflictions and the tribulations which

have plagued and sought to tear apart the

multicultural pluralistic ethos and the

socio-cultural ambience of

Kashmir

, Mauj Kashir as

Kashmiris call it reverentially.

In

poem after poem, the verse pieces even qualify as

a hypertext, a text that builds on or contains

traces of an earlier text. Though “Homeland

After Eighteen Years” can by no means be called

as a sequel to Chowdhury’s maiden work “Of

Gods, Men and Militants” (2000), yet it does

awake in our minds as readers, the agonizing

apostatic events recorded in the author’s very

first work as an infallible specimen of diasporic

literature written in exile. To quote some lines

would be appropriate to illustrate this writer’s

point-of-view.

A

debate is sparked in the poet’s mind:

“Kashmir

has never left my thoughts /ever since I left her,

18 years back.

I

roam the lanes and by lanes/ of the home where I

was born,

the school I learnt my three Rs,/and the

hospital I worked and taught.

That was my small beautiful world/that I

would loathe exchange

even for paradise”.

How

poignant these lines become in conveying to the

reader the sheer metaphysical and psychological

agony of separation from one’s homeland and the

resultant rootlessness, anomie and angst.

Look

at these lines, unforgettable ones:

“I

often recall my friends in

Kashmir

/and remember them

beyond

their religious identities,/ and before the time

there was anything

like/ ‘them’ and ‘us’.

And

again:

“to

receive an award in person/is an honorable

proposition;

stronger

is the urge for a reunion/ with people and places

where

I spent all my childhood and prime/and my middle

years…..

where

all my forefathers lived and died,/where my soul

doth residep;

That

the award is just an excuse/thrown my way by

providence

to

fulfill my intense longing/ for a rendezvous with

the valley”.

About

the vitasta (river Jehlum), the author feels what

one can feel and say about the demonic

degeneration of the mineral world of pastoral

symbolism:p;

Alas,

what offers the sight/

is a lazy, almost stagnant stream,

duckweed

and refuse, and an occasional animal carcass

floating

on her sullied surface.

There

is no evidence, whatever,/

of her youthful voluptuous way

And

the river n deep depression/bemoaning the

valley’s transformation…

In

the quoted lines we witness the formation and

creative expression of a diasporic identity,

anchored in narrative brilliance - a form of

interpretive activity, a process of storytelling

constrained by cultural and social upheaval.

Chowdhury’s verse pieces across the pages of

“Homeland after Eighteen Years”, cumulatively,

form a narrative spectrum, an autobiographic

collage ranging from recollections of specific

events and individuals to an extended account of

virtually a lifetime experience. The connection

and the relationship between narrative and

identity, has been fruitfully explained umpteen

times. Yet, the realistic phenomenological

auspices employed by the author, vis-à-vis his

undying nostalgia and love for his lost homeland,

transform the present work as a narrative in the

form of an epistemic structure that makes reality

intelligible to us. Stories may not be lived but

only told; all the same, Chowdhury’s supple,

pliant, lucid and free-flowing lines as

travelogue, traveling back and forth in time, grip

the reader’s mind with a hypnotic tide of

emotions, recollections and attachments. Realism

combines with a distinct communitarian streak, the

author’s life in spite of enforced exile, is

narrated as a consequence of the embeddedness of

individual lives in the existence of a community:

“People

have seen through the militants,

and

the leaders who stoke their passions.

Be

it the subversives and separatists,

be

it the politicians and the ideologues,

they

all have their axe to grind;

they

give a damn for the common man

who

is dragged into this

for

no fault of his.”

Pathos

mixes with agonizing helplessness when the author

narrates that the gods and deities feel abandoned

and forgotten by their devotees who left the

valley during the enforced exodus, almost two

decades back:

“I

have no heart to go in/and seek a darshan,

for

I will have a lot to answer/to the deities

inside

that

we worshipped every day,/and a lot to hear

from them.”

These

lines refer to the famous

Ramchander

Temple

, near the

Barbarshah

Bridge

in

Srinagar

. About the Ganesha temple at the foothills of

Hariparbat fort, the lines become a virtual dirge

lamenting a lost divine glory coupled with the

absence of eager devotees and worshippers, who

would once flock to pay obeisance to the elephant

god:

“Smeared

with deep vermilion, the mound of rock here

is

naturally shaped, like the potbellied Ganeshap;

with

an elephant head and

a curled trunk,

who

has evoked such adulation down the ages.

But,

now, the rock is defaced and laid bare,

the

image tarnished beyond repair,

and

dear Ganesha, deserted by his devotees

looking

worn, forlorn and melancholy.p;

After

a visit to Pokhribal, the poet in Chowdhury

wonders:

“Who

is worse off, I wonder-

the gods here sans their flock

or the flock in exile sans their gods?”

At

Makhdoom Sahib, the author finds

“men, woman and children

praying, shedding tears, tying knots,

their faces lit up in faith.”

Yet,

he fails to understand:

“how one faith can thrive on the damnation of another;

how

can love for one nourish on hatred for the

other?”

Toward

the end of the book, when the author is back in

the Circuit House after the Award Ceremony, he

speculates about the Mindset of a top government

functionary “Who rues that good doctors and

teachers have become scarce in

Kashmir

after the Pandits ‘fled’.” The word

“fled” as a misnomer, a blatant travesty of

truth about the reason behind the enforced exodus

of Kashmiri Pandits from the valley, makes the

poet in Chowdhury register his reaction in

no-holds-barred poesy:

“I

was incensed by that word/ for it is a common

canard,

a myth perpetrated……../ that the Pandits ‘fled’

Kashmir

that they deserted their homes and hearths/for the unknown terrains of

exile”

Deliberate

disinformation and falsehood is sought to be

dispelled in these words:

“For,

it is not the common man/ but the bureaucrat

and the

manager,

the politician and the minister,/ who do not want the Pandits back”.

it is they who are the worst offenders/of our human rights

and not the common Kashmiri Muslims/who, like Rauf, would want us back”.

The climactic poem in the collection “The Return

Flight” sums up, what Leslie Fielder said about

creative, realistic technoscapes: “Cross the

border and close the gap….” On landing back at

Jammu airport, the author, himself now enriched by

the tribulation of an ‘anonymous’ identity in

what once was his homeland feels, and truly so,

that the place which has hosted him for “full

eighteen years” (Jammu) is in reality now his

home:

“How come we never owned it

as it owned us?

……..

Suddenly, I get a feeling,/

first time in these long years,

that I am returning home.

No, I am not a refugee;

this place belongs to me,

and I belong here.

A homeland for me/is a place

which gives me back my identity.”

Thus, as a postmodern ‘time-traveler’,

Chowdhury not only experiences the ironic,

paradoxical self-reflexivity in those 48 hours of

his hurricane visit to the valley, “the

paradise” turned into hell that man creates on

earth, these 48 hours, symbolically epitomize the

48 years of his life at the time of his exodus

from the place of his birth. The entire verse

pieces in “Homeland after Eighteen Years”

constitute dialogism of utterance and of the text

as utterance. Chowdhury’s 48 hours sojourn in

Kashmir

becomes a carnivalesque capsule of the first 48

Years of his earthly existence. The author was

nearly 49 when he had to bid adieu to his dear

homeland. “Homeland after Eighteen Years”,

qualifies as a work which fuses, and poetically

blends, the metaphysical and geographical terrains

of an author, who, like Albert Camus’s Sisyphus,

arrives at his own existential resolution.

|

No one has commented yet. Be the first!