Thoughts about Homeland

BOOK REVIEW

The book is a sensitively written

narrative, an account of events and experiences,

cast in a poetic mould.

Prof M L Raina

June 2011

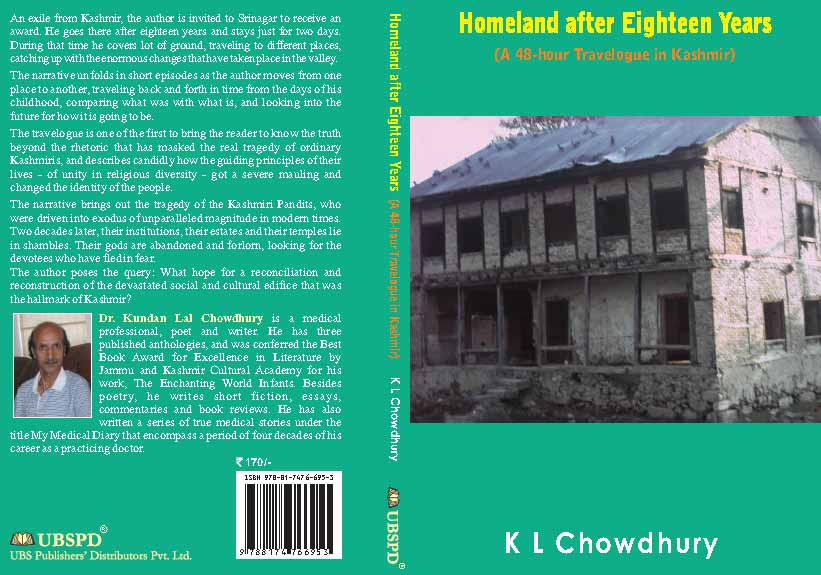

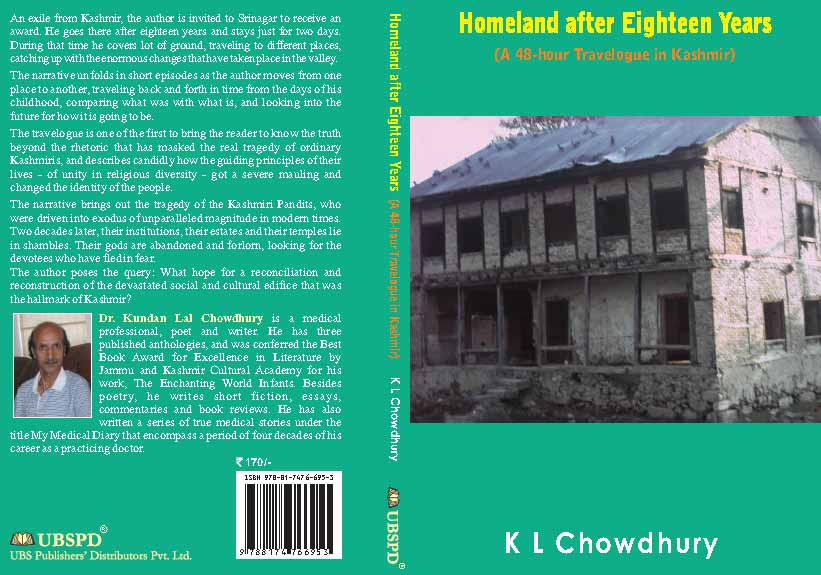

At a subtle level of perception, the

anthology entitled “Homeland After Eighteen

years”, by Dr K L Chowdhury, seems to be a

poetic bioscope, presenting myriad scenes and

sights of the historical city of Srinagar and its

outskirts. At a subtler level, it is a work of

pure poetic magic that casts a spell on the

reader, preparing him for flights of imagination.

A powerful description of the features of the

city, enlivened with the author’s “modifying

colours of imagination” cannot but touch the

inner chords. The author lifts the reader as it

were on the “wings of poesy” to give him a

firsthand feel of what the city looks like and

what it looked like by contrast before a deep and

destabilising pall of gloom descended on it,

eclipsing its bright and beautiful looks. Creating

empathy in the reader, the author makes him walk

along with him and visit various areas of Srinagar.

In the process, he takes him up the hills and down

the dales, through the streets, big and small,

rivers and pools, lakes and gardens, high rise

buildings, dilapidated structures, malls and burnt

houses and so on and there come tumbling down on

the mind of the reader painfully pleasant

memories.

The book is a sensitively written narrative, an

account of events and experiences, cast in a

poetic mould. It is a fine blend of pathos and

subdued pleasure. The poet’s nostalgia is so

overpowering that, to quote him, “I would die to

be there again for once, if only once” and

“strong is the urge for a reunion with people

and places”. The thrill of the anticipated

reunion is, however, diluted and his bubbling

enthusiasm cooled down when he conforms the

dismally changed environs of once the “paradise

on the earth” while coursing through the city,

coupled with his ever present feeling of anguish

and pain his community members have been through,

having been driven out their ancestral land and

obliged to live as refugees outside, away from

“the ashes of their fathers and the temples of

their gods”.

Dr. Chowdhury is bitterly critical of “What

man has made of man” in the peaceful and sedate

city of yore, the pride of its people, and the

envy of the visitors from outside. He describes

painfully the scenes of the destruction of men and

material. There are flashes of several accusations

in the narrative, directed against the insensate

Jihadis, the enemies of peace, prosperity,

and the good old values of communal amity and

brotherhood, social cohesion, civilised behaviour,

and decency of attitude. This impression is

conveyed in the following lines:

‘What place for values and ideals

Where religious bigotry holds sway,

Where divisions and discord prevail

Over reason or rationality?’

Blatant hypocrisy of the Jihadis and their

sympathisers of all hues, who call themselves

devout religionists, is exposed by the author in

these lines:

‘The mandarins and ministers.

The politicians………

The high officials and the lowly workers-

One and all-

Have joined the loot’

The forced exodus of the Kashmiri Pandits, with

its pathetic consequences, is the recurring theme

of the narrative. Their pitiable condition of

uncertainty and the pain of exile find an echo in

the bard’s lament:

“We look before and after,

And pine for what is not”

When they think of the past, their raw wounds

are ripped open. When they think of the future, a

sense of dismay overtakes them, because they are

not sure of what the future holds for them. They

eagerly long for what they have been brazenly

denied at present.

All the poems in the book have a charm of their

own, but the one titled “The Audience” stands

out as a grand and sublime poetic piece, with a

profound religious import. The poet is candid

about his faith in the divine and divine

intervention. His reverential awe comes to the

fore when he looks at the stone image of his

beloved Lord Shiva in the temple of Shankaracharya.

When he approaches the idol to touch it, his hands

quiver, and an electrifying divine wave sends a

shiver through his mortal frame and he remains

immersed in ‘celestial joy’ that is marked by

inner peace. His passion for the divine embrace is

so intense that he wants to give himself up to the

divine presence, body and soul.

This, he feels intuitively, is the right place

and time for him, not to offer material oblations,

but to offer his whole being, as expressed in

these lines:

“I have come to offer myself,

My entirety,

My essence”

The author seems to firmly believe that

“there is destiny in the affairs of men”. He

says that the award ceremony at Srinagar to honour

him was an excuse, an act of divine intervention,

to grant him the long cherished prayer for

visiting his motherland. He sees destiny’s hand

in sending a doctor (the author) to the doorsteps

of the ailing priest in the temple.

The narrative, though subjective in nature, has

an air of objectivity about it, in so far as it

holds a mirror to the smeared soil of Srinagar for

all to see, including the Jihadis who perceive

beauty in every scene of ugliness. As for the

Pandits, the narrative unfolds the saga of

sufferings and deprivations they have faced. When

all this is recapitulated through the medium of

songs, they effect catharsis of their pent up

feelings and loosen their emotional baggage, thus

providing some reprieve.

The style of the narrative is marked by

lucidity of diction and felicity of expression.

The technique of moving forward and backward in

time, use of historical present to lend poignancy

to a scene depicted or a thought expressed, use of

varying rhythmical patterns of lines, to suit the

shifting events and moods, use of apt figures like

metaphors and similes, sensuous touches here and

there and above the all use of brilliant images-

all these enhance the grace of the subject matter.

Such is the poetically treatment given to an

otherwise gloomy content of the narrative that the

reader would love to read the book over and again,

for, verily “Our sweetest songs are those that

tell of the saddest thoughts.”

Source: Kashmir

Sentinel

|

No one has commented yet. Be the first!