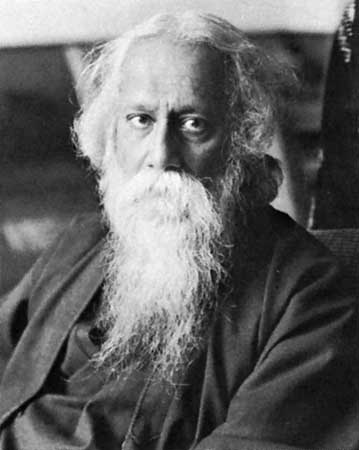

Rabindranath Tagore

Shining Star of Indian Horizon

by Chander M. Bhat

Rabindranath Tagore is considered as India’s

greatest

modern poet and the most creative genius of the Indian Renaissance. His life

span was roughly coeval with that of British imperial rule in India. He was born

on 7th May 1861 at the Tagore family home in Jorasanko, Calcutta, in a rich and

talented family that had already begun to make its mark on contemporary society.

For the elite of undivided, Bengal it was an exciting time, despite the British

presence, and indeed partly because of the new things that were happening

because of that very presence. The name Tagore is an anglicized version of

Thakur, cerebral and aspirated, and is actually a surname that was acquired by

the family only accidentally, the real family surname having been Kushari. In

the last decade of the seventeenth century, Rabindranath’s ancestor Panchanan

Kushari settled in Gobindapur, one of the three villages which went into the

making of Calcutta, and earned his living by supplying provisions to the foreign

ships which sailed up the Ganges. Being a Brahman, he was respectfully addressed

by the locals as ‘Panchanan Thakur’. The family acquired special prestige under

the dynamic leadership of Rabindranath’s grandfather, Dwarakanath Tagore, who

acquired large landed estates, built up a substantial business empire,

fraternized with the European community, and was generous in his public

charities. He was a close friend of Raja Ram Mohan Roy, one of the front-rank

thinders and activists of the Bengal Renaissance. Dwarakanath’s eldest son,

Debendranath, at first enjoyed the luxury in which he had been reared, but then

came a raaction. He was devoted to his grandmother. greatest

modern poet and the most creative genius of the Indian Renaissance. His life

span was roughly coeval with that of British imperial rule in India. He was born

on 7th May 1861 at the Tagore family home in Jorasanko, Calcutta, in a rich and

talented family that had already begun to make its mark on contemporary society.

For the elite of undivided, Bengal it was an exciting time, despite the British

presence, and indeed partly because of the new things that were happening

because of that very presence. The name Tagore is an anglicized version of

Thakur, cerebral and aspirated, and is actually a surname that was acquired by

the family only accidentally, the real family surname having been Kushari. In

the last decade of the seventeenth century, Rabindranath’s ancestor Panchanan

Kushari settled in Gobindapur, one of the three villages which went into the

making of Calcutta, and earned his living by supplying provisions to the foreign

ships which sailed up the Ganges. Being a Brahman, he was respectfully addressed

by the locals as ‘Panchanan Thakur’. The family acquired special prestige under

the dynamic leadership of Rabindranath’s grandfather, Dwarakanath Tagore, who

acquired large landed estates, built up a substantial business empire,

fraternized with the European community, and was generous in his public

charities. He was a close friend of Raja Ram Mohan Roy, one of the front-rank

thinders and activists of the Bengal Renaissance. Dwarakanath’s eldest son,

Debendranath, at first enjoyed the luxury in which he had been reared, but then

came a raaction. He was devoted to his grandmother.

Records left of Debendranath’s wife, Sarda Devi,

portrays her as a pious woman devoted to her husband and an astute matron in

charge of her vast household. She cultivated the habit of reading religious

works in Bengali, Rabindranath was her fourteenth child. So Rabindranath was

effectively his parent’s youngest offspring.

Fortunately, Rabindranath Tagore was one of those who go on educating themselves

throughout their lives. He read widely. His enlightened and sympathetic brothers

encouraged him to learn at his own pace and discover things for himself. His

father taught him to love the Upanishads, aroused in him an interest in

astronomy that was to last all his life, and allowed him to combine a literary

career, which did not require degrees, with the management of the family

estates. Rabindranath was well grounded in the Sanskrit classics, in Bengali

literature and in Engligh literature, and also familiar with a range of

Continental European literature in translation. He could read some French,

translated Engligh and French lyrics in his youth, and made enough progress in

German to read Heine and go through Goethe’s Faust. In the end his own extended

family and the state of cultural ferment all around him gave him the environment

of a university and an arts centre rolled into one. It was in a cultural

hothouse that his talents ripened. A man emerged, who had his father’s spiritual

direction and moral earnestness, his grandfather’s spirit of enterprise and joie

de vivre, and an exquisite artistic sensibility all his own.

Rabindranath wrote poetry throughout his life, but he did an amazing number of

other things as well. Those who read his poetry should have at least a rough

idea of the fuller identity of the man. His long life is as densely packed with

growth, activity, and self-renewal as a tropical rainforest, and his

achievements are outstanding by any criterion. As a writer he was a restless

experimenter and innovator, and enriched every genre. Besides poetry, he wrote

songs , short stories, novels, plays, essays on a wide range of topics including

literary criticism,polemical writings, travelogues, memoirs, personal letters

which were effectively belles letters, and books for children. Apart from a few

books containing lectures given abroad and personal letters to friends who did

not read Bengali, the bulk of his voluminous literary output is in Bengali, and

it is a monumental heritage for those who speak the language. Like the other

languages of northern India, Bengali belongs to the Indo-European family of

languages. A cousin to most modern European languages and sharing with them

certain basic linguistic patterns and numerous cognate words, it is spoken by an

estimated 180 million people in India and Bangladesh. When Tagore began his

literary career, Bengali literature and the language in which it was written had

together begun a joint leap into modernity, the most illustrious among his

immediate predessors being Micheal Madhusudan Datta in verse and Bakimchandra

Chatterjee in prose. By the time of Tagore’s death in 1941 Bengali had become a

supple modern language with a rich body of literature. Tagore’s personal

contribution to his development was immense. The Bengali that is written today

owes him an enormous debt. Throughout his life Tagore maintained a strong

connection with the performance arts. He created his very own genre of dance

drama, a unique mixture of dance, drama, and song. He not only wrote plays, but

also directed and produced them, even acted in them. He not only composed some

two thousand songs, but was also a fine tenor singer. He was not only a prolific

poet, but could also read his poetry out to large audiences very effectively.

Many of his contemporaries have attested that to hear him recite his own verses

was akin to a musical experience.

In the seventh decade of his life Tagore started to draw and paint seriously.

Tagore was a notable pioneer in education. A rebel against formal education in

his youth, he tried to give shape to some of his own educational ideas in the

school he founded in 1901 at Santiniketan. The importance he gave to creative

self-expression in the development of young minds will be familiar to

progressive schools everywhere nowadays, but it was a new and radical idea when

he introduced it in his school. The welfare of children remained close to his

heart to the end of days. To his school he added a university, Visvabharati,

formally instituted in 1921. He wanted this university, to become an

international meeting place of minds, ‘where east and west to come and enrich

its life. Under his patronage, the Santikiketan campus became a significant

centre of Buddhist studies and a heaven for artists and musicians.

Through his work in the family estates Tagore became familiar with the

deep-rooted problems of the rural poor and initiated projects for community

development at Shilaidaha and Potisar, the headquarter of the estates. At

Potisar he started an agricultural bank, in which he later invested the money

from his Nobel Prize, so that his school could have an annual income, while the

peasants could have loans at low rates of interest. Tagore does not belong to

Bengalis or Indians only. But the poetry of Tagore has attracted the whole

literary world. In 1913 Nobel Prize for literature was awarded to Tagore for 'Gitanjali'.

Yet the Nobel Prize was definitely a landmark in Tagore’s life. It made him

internationally famous. He reached a worldwide audience, received invitations

from any countries, traveled and lectured widely, acquired foreign friends, and

thanks to his fame, met many other distinguished personalities of his time.

After a life of incessant creative activity, Tagore died, at the age of eighty

years and three months, on 7th August 1941, in the family house in Calcutta

where he had been born. The quality and quantity of his achievements seem all

the more astonishing when placed against the amount of grief he had to cope with

in his personal life. Much of his poetry is necessarily about love and

suffering, about how one copes with loss, and can be called passional

affirmative and celebrative poets of all times.

|