Dards - An Indo-Aryan Race

by Chander M. Bhat

Ladakh, derived from Tibetan La-Tags

denotes a land of passes

and mountains. It is also referred as May-Yul, low land or red land and

Kha-Cha-Pa or the snow land.

Ladakh is a land like no other. Bounded by two of the

world’s mightiest mountain

ranges, the Great Himalaya and the Karakoram, it lies athwart two others, the Ladakh range and the Zanskar range. In geological terms, this is a young land,

formed only a million years ago by the buckling and folding of the earth’s crust

as the Indian sub continent pushed with irresistible force against the immovable

mass of Asia. Its basic contours, uplifted by these unimaginable tectonic

movements, have been modified over the millennia by the opposite process of

erosion, sculpted into the form we see today by wind and water. Ladakh is

inhabited by a peculiar race of people, who speak a peculiar language and who

profess Buddhism, under a peculiar hierarchy of monks called ‘Lamas’. world’s mightiest mountain

ranges, the Great Himalaya and the Karakoram, it lies athwart two others, the Ladakh range and the Zanskar range. In geological terms, this is a young land,

formed only a million years ago by the buckling and folding of the earth’s crust

as the Indian sub continent pushed with irresistible force against the immovable

mass of Asia. Its basic contours, uplifted by these unimaginable tectonic

movements, have been modified over the millennia by the opposite process of

erosion, sculpted into the form we see today by wind and water. Ladakh is

inhabited by a peculiar race of people, who speak a peculiar language and who

profess Buddhism, under a peculiar hierarchy of monks called ‘Lamas’.

Ladakh lies at altitudes ranging from 9000 feet at Kargil to 25170 feet at Saser

Kangri in the Karakoram. The summer temperature rarely exceeds about 25 degree

in the shade, while in winter temperature is extremely low. Surprisingly,

though, the thin air makes the heat of the sun even more intense than at lower

altitudes; it is said that only in Ladakh can a man sitting in the sun with his

feet in the shade suffer sunstroke and frostbite at the same time.

Many nomadic tribes migrated through high

Himalayan regions towards second and mid third millennium. Mons and Dards first

carried B.C. Buddhism to Ladakh. Later after 9th century Mongolians

of Tibetan origin strengthened Buddhism. Like other tribes Dards migrated to

inner and outer Himalaya from various entrance points and settled down along

with fertile Indus Valley. Thereafter some of them migrated to Ladakh region

from Hunza.1

Ethnologically Dards are of the Indo-Aryan

stock. It is said that they are the survivors of Alexander’s troops, who after

their generalissimo departure scattered over Indus Valley lying between Kylindrine and Dardi meaning Kulu and Dardistan.2

After Muslim invasion in the 14th

century, Dards, who were settled in Drass, embraced Islam.3 On the

other hand, Dards of Da, Hanu, Biama and Garkon villages neither accepted Islam

nor Lamaism. Some historians are of the opinion that the migration of Da-Hanu

people, took place after the conversion; consequently they are the only Buddhist

Dards left in existence. And yet their Buddhism is very different from that of

the Buddhism of central and eastern Ladakh. Their customs differ markedly from

those of the Tibetan-descended population of those areas; and their cosmic

system, as expressed in the hymns of their triennial Bona-na festival,

show distinct traces of the pre Buddhist animistic religion known as Bon-chos.

They are known as Drokpa, people of the pastures; and among the

most striking of their customs is a dread, and almost complete avoidance, of

washing. For ceremonial purification they burn the fragrant twinges of the

pencil cedar.4 Distinguished by their non-Tibetan features, they are

for the most part carpenters and musicians; all the professional musicians, the

players of Surna and Daman, are Mon; and in particular contents

the word Mon has come to have the secondary meaning of musician.5

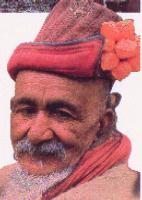

Da, Hanu (see photograph), Biama and Garkon villages can be found on the

northern bank of the Indus en-route Chorbat-la pass, near present Indo-Pak

border, some 208 km from Leh (see map). The locals are Aryan residents.

According to a popular belief the inhabitants (2300 souls as per 1981 Census of

Jammu and Kashmir, Kargil District) of these villages are direct descendants of

the original Aryans and are open people, good to talk. Though not exceptionally

tall, the fair skinned, high cheek boned youth of the Aryan community makes one

impressed. During my posting at Leh in the year 2001, I went to see the Aryans

in their own surrounding and spoke to them. Stories doing rounds those young

German women came all the way from Europe for the pure seed of the original

Aryan men, wanting to be impregnated by them to start the pure race again. Till

sometime back, they did not marry outside their community to preserve the purity

of their race. Drokpas can easily be distinguished from Ladakhis by their fine

features, well-proportioned limbs and fair complexion. They are sharp featured,

tall with relatively long head; the nose aquiline sometimes straight like

Kashmiris; face long and symmetrically narrow, with a well developed forehead;

the features are regular and have broad shoulders; stoutly built, and well

proportionate bodies, excellent mountaineers and hill porters, fairly good

looking with black hair. By complexion they are moderately fair and the shade

light enough to allow the red to show through hazel. Most men sport beards.

Women wear their hair in long plaits. Men, women and children have their ears

pierced and wear metallic rings in them. They wear colourful caps; decorate them

with dry red flowers and silver coins (photograph). They wear homespun dresses,

made of sheep wool.6

Drokpas have preserved folk takes of

their heroes. The longest ballad concerns the Chief and foremost here ‘Kesar’7,

as an old Drokpa tells this story about Kesar.

“To us he (Kesar) is the son of the heavenly god, who sent him down the earth in

a human form to help human beings. He even changed his appearance and turned

himself into the grab of a beggar when he was looking at the land of princess

Breugmo. Her parents rejected him. He then performed many feats of bravery, and

was accepted as a son-in-law by them. When the king of China got ill, it was

Kesar who healed him. The daughter of the Chinese king eloped with Kesar who was

chased by the dragons. After having overcome many hazards, he reached his place

and lived with his two queens. The later part of the epic deals with Kesar’s

battles with the ‘Jinni’ of the north.8

Drokpas celebrate their special harvest festival once in three years.

They call it ‘Chhaipa’, ‘Sarupalha’ or ‘Bona-na’, which means the festival of

fertility. This is the biggest festival among the Drokpas and it lasts

for three days. The people of all the villages assemble on a particular place

earmarked for this purpose and elderly persons of the village singsongs, worship

a common god ‘Labdraks’. Young boys and girls dance on this occasion that is

known as Brokpa dance and marriages are also settled on this festival.

The, would be couples exchange their views on this occasion. They also exchange

valuable costumes and then express their great joy.

Drokpas do not use cow’s milk and its products. It is believed that if by

mistake one takes the cows milk, his god will be displeased and in the

consequence his family members will come under the grip of disease called red

boil disease. Even the dung of a cow is not used as fuel and as manure, as it is

believed that the dung is highly offensive to their gods. In case any Drokpa

keeps a cow, he allows the calf to drink the cow’s milk, so that it grows fast

and become healthy so that they can sell it at a good price outside Drok-yul.9

Drokpa consider horse as a sacred animal and worship it for good

crop production. It is a great honour for them it they have a horse in their

house especially the white horse.

Drokpas believe that sun is god, which

gives heat to the earth, and it is believed that by worshipping the sun they

would become prosperous, healthy and get good vegetation. There is a

superstition prevalent among the Drokpas that in childhood every child

should have to wear a circular metal dise round the neck, because it protects

from the evil effects of the sun.

Drokpas are great carvers. They drew many

carvings on rocks and the same can be seen even today. Most of the carvings

depict the image of Buddha. These carvings are mostly carved during the

festival season.

Apple, mulberry, apricots, walnuts, cherry,

peaches, pears and grapes are abundantly grown in these villages. The locals

worship walnuts and collect (Doon

Chanen, in Kashmiri) the same on a

particular day and nobody eats walnut before that day even if the walnuts fall

to the ground of its own. Like Kashmir, walnut trees are found in every house

either in front or in back compound. Every house is having a kitchen garden and

some portion of it is covered with the plastic sheets to form a green house and

vegetables are grown in these green houses in winter season.

Thus the Dards have preserved their old traditions even after absorbing Tibetan,

Muslim and other cultural influences. Rohit Vohra says:

“The Buddhist Dads of Ladakh form an ethnic entity. Their traditions show a

capacity to adapt themselves to new influences yet retaining their belief system

within whose framework an adjustment is arrived at. The logic of rationality

determining the continued existence of their beliefs can be seen in their social

organization and religious system which have absorbed Tibetan and Buddhist

ideas”.10

NOTES &

REFERENCES

-

Bedi, Ramesh: “Ladakh’, Brijbasi Pub. Co.

-

Hassbaub, F.M.: ‘The Brukpa Dads, in: ‘Ladakh Life & Culture”

K.N.Pandit (ed), Central Asian Studies, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, 1986,

p.27.

-

Francke A.H. : ‘Ladakh: The Mysterious Land’, Ess Ess Pub. New Delhi,

1905/1950 reprint, p.28.

-

Rizvi, Janat: ‘Ladakh’ Crossroads of High Asia, Oxford University

Press, p. 131-132.

-

Mark Trewin: ‘Rhythmic Style in Ladakh…Music and Dance’, in Schwalbe

and Meier (eds).

-

Bedi, Ramesh: op. cit., p.27.

-

Kaiser: Kasar,

Geser, Keiser, Geiser, Geiser Khan: Kaiser stories are

like spices. Kaiser epic takes several days to be told. The story telling itself

is an art, which only few individuals acquire. The stories are passed down from

generation to generation and are learned by heart. The story telling itself

takes a fairy specific form, in which rhythm, and the odd stanza which is sung,

make it distinct from colloquial Ladakhi. The tradition is an oral one; no one

is allowed to tell the stories during summer. The storyteller only tells the

stories during winter, through several versions. (Cf. Tsering Mutup’ Kesar Ling

Norbu Dadul, In: Recent Research on Ladakh, Detlef Kantowsky, reinhard Sander

(ed), Weltforum Verlag Pub. London, 1983 p.9.

-

Hassnain, F.M.: op. cit, p. 31.

-

Jina, Prem Singh: ‘Ladakh’ The Land and the People, Indus Pub. Co.,

New Delhi.

-

Vohra Rohit: ‘History of the Dards and the Concept of Minaro

Traditions among the Buddhist Dads in Ladakh’. In recent research on Ladakh (ed)

Detlef Kantowsky, reinhard sander, Waltforum Verlag, London, 1983, p.79 quoted

from Marx, K.: ‘Three documents relating to the History of Ladakh’. In journal

of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol LX, Part I, Calcutta, 1891; Frankce, A.H.:

‘Antiquities of Indian Tibet’, Delhi, 1926/1972 reprint, Vol I, p. 93; Petech,

L.: ‘The Kingdom of Ladakh’, c 950-1842 A.D. Serie Orientale, Is MEMO, Vol LI

(1977), pp. 16-17.

|