Bumzu Temple

by Chander M. Bhat

Anantnag is located between 330-20'

to 340-15' north latitude and 740-30' to 750-35' east longitude,

bounded in the north and north-west by Srinagar and

Pulwama districts respectively and in the north east

by Kargil district. It is the most fertile district in

the Kashmir valley and is called as “The granary of Kashmir”. Anantnag is

also known as the “Gateway to Kashmir valley”.

The district is renowned for its rich cultural heritage and hospitality. It is

also a symbol of secularism and tolerance. These qualities have bound the people

of the district together for centuries. All sects of the society live in harmony

without any prejudice. They are credited to have unity in diversity.

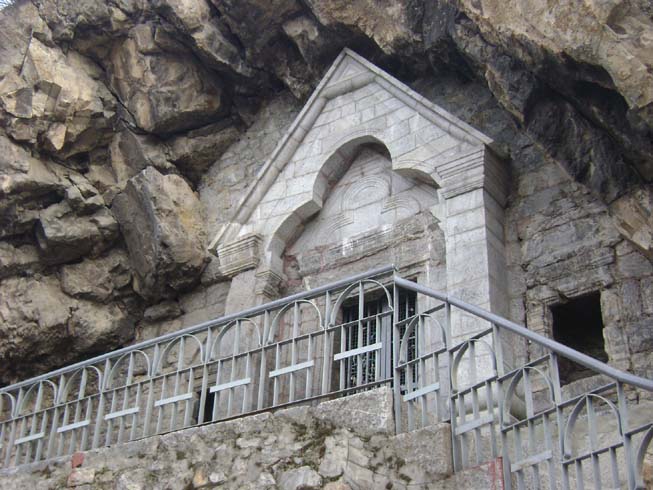

Close up of the main entrance of the cave.

Anantnag

has for long enjoyed the status of the second largest city of the Valley. The

name of Anantnag District according to a well known archaeologist, Sir A. Stein

from the great spring Ananta Naga issuing at the southern end of the town. This

is also corroborated by almost all local historians including Kalhana according

to whom the town has taken the name of this great spring of Cesha or Ananta Naga

land of countless springs. The spring is mentioned in the Neelmat Purana as a

sacred place for the Hindus and Koshur Encyclopedia testifies it.

Before

the advent of Muslim rule in 1320 A.D., Kashmir was divided into three

divisions, viz; Maraz in the south, Yamraj in the centre and Kamraj in the north

of the Valley. Old chronicles reveal that the division was the culmination of

the rift Marhan and Kaman, the two brothers, over the crown of their father. The

part of the valley which lies between Pir Panjal and Srinagar now called the

Anantnag was given to Marhan and named after him as Maraj. While Srinagar is no

longer known as Yamraj, the area to its north and south are still called Kamraz

and Maraz respectively. Lawrence in his book ‘The Valley of Kashmir’ states

that these divisions were later on divided into thirty four sub-divisions which

after 1871 were again reduced to five Zilas or districts.

Shiv Lingam

Anantnag

like the rest of the Kashmir Valley has witnessed manyvicissitudes and

experienced many upheavals from time to time. Hugel found here some monuments of

the Mughal period in ruins when he visited Kashmir in 1835. No significant

ancient building or archaeological site is found in the district today except

the Martand temple. What must have once been magnificent architectural show

pieces like the Martand complex of temples situated at a distance of nine

kilometers from the district headquarters or the palaces of Laltaditya and

Awantivarman at Awantipora lying midway between Srinagar and Anantnag town are

now in grand ruins. The majestic Martand temple is one of the important

archaeological sites of the country. Its impressive architecture reveals the

glorious past of the area. Martand temple is the clear expression of Kashmir’s

pristine glory. The Mughal Emperors especially Jehangir developed many beauty

spots of the district, but of their noble and magnificent edifices only fainted

traces survive. All the same, even in their present ruinous conditions, these

monuments do not fail to feast the eye or excite the imagination of admirers at

large.

Anantnag

district is bestowed with religious wealth in the forms of numerous shrines and

places of worship. These worth visiting places include Mattan (Bawan) Temple,

Martand Temple, Holy Cave of Amarnath Ji, Ziarat Hazrat Zain-ud-Din Wali, Nagbal,

Khir Bhawani Asthapan (Devibal), Uma Devi of Uma Nagri, Bumzu or Bhaumajo Caves,

Chapel of John Bishop and Nagdandi.

Ancient

monuments of very great archaeological interest which disclose the existence of

a lost civilization are, numerous in Kashmir. The devotion of kings, the

reserves of the kingdoms and skills of master artists in the past combined, to

raise the magnificent and the beautiful temple edifices in Kashmir. They were

built to endure for all times. Their solidity of construction and their gigantic

size strike one with wonder that man could have built them. Many kings have come

and gone and civilizations have bloomed and vanished since they were built.

People go and pace around them and gaze on them with amazement and awe -

amazement inspired by the stupendous might and skill of their builders and awe

excited by the ruins of these edifices which look as if weeping over the

departed glory of their founders.1

Bumzu

is a place at a distance of 1 km from Mattan enroute Anantnag. The place is

famous for three cave temples situated on the left bank of Liddar, 60 feet above

at a close distance to each other. The entrance to one of the caves is carved

architectural doorway, which through a passage leads one to the cave temple. The

temple, 10 feet square, is on a raised platform and is reached by a flight of

steps. The old square doorway had statues, which were defaced. The second cave

temple is close by and is slightly bigger in size but without any architectural

designs and is said to be dedicated to Kaladeva. An Icom exists in this cave

temple. Nearby is alsos the third cave temple, which is also without any

architectural design.

There

is a legend, which gives the origin of these cave temples and links the Bumzu

caves and the shrine of Chakradhara with King Nara. Walter R. Lawrence while

giving reference to Hugel says that King Nara succeeded his father Vibishana in

the year Kali 2108 (993 BC0. One day, he beheld Chandrasaha, the daughter of

Susravas, a serpent-god, whose place was in a lake and decided to carry her away

from her husband, a Brahmin. The plan failed, upon which the enraged Brahmin

asked Surravas to avenge the insult. A storm was called up and the earth oopened

and swallowed the king and his whole Court. The sister of the serpent-god

assisted him and hurled on the city huge stones from the Martand Mountain. The

cavern of Bhumju are said to be on the spot where these rocks were uptorn.

According to Aurel Stein, “A young Brahman, who had found occasion to assist

the Naga and his two daughters when in distress, was allowed to marry in reqard

one of the latter. He lived in happiness at Narapura until the beauty of the

Naga lady excited the passion of the wicked king. When Nara found his advances

rejected, he endeavoured to seize the beautiful Candralekha by force. The couple

thereupon fled to protection to their father’s habitation. The Naga then rose

in fury from his pool and “burned the King with his town in a rain of fearful

thunderbolts.” Thousands of people were burned before the image of Vishnu

Chakradhara, to which they had fled for protection.

Ramanya, the Naga’s sister, came down from the mountains carrying along masses

of rocks and boulders. These she dropped, as we have seen, along the bed of the

Ramanyatavi or Rambiyar stream, when she found that Susravas had caused, removed

to a lake on a far-off mountain.”

The Nag where the couple took shelter came to be known as Zamtiur Nag. The lake

mentioned in the reference is known as Takshak Nag at Zewan, named after Takshak

Raza, the Lord of snakes.2

According

to Sir Walter Roper Lawrence, “Bhumju or Bumzu or Bhaumajo lines at the mouth

of the lidder valley, and easily reached from Islamabad. These caves are

situated on the left bank of the Lidder river about a mile north of the village

of Bawan, the largest is dedicated to Kaladeva. The cave-temple stands at

the far end of a natural but artificially enlarged fissure in the limestone

cliff. The entrance to the cavern, which is more than 60 feet above the level of

the river, is carved into an architectural doorway, and a gloomy passage, 50 ft

in length, leads from it to the door of the temple. It is a simple cella, 10 ft

square , exterior dimensions, raised on a badly moulded plinth and approached by

a short flight of steps. The square door way is flanked by two round headed

niches despoiled of their status and is surmounted by a high triangular pediment

reaching to the apex of the roof, with a trefoiled tympanum. There is no record

nor tradition as to the time of erection but from absence of all ornamentation

and the simple character of the roof, which appears to be a rudimentary

copy in stone of the ordinary slopping timber roof of the country, it may with

great probability be inferred that this is the earliest perfect specimen of

Kashmir Temple, and dates from the 1st. or 2nd century of the Christian

era. Close by is another Cave of still greater extent, but with no

architectural accessories and about half a mile further up the valley at the

foot of the cliff, are two temples. Both are , to a considerable extent, copies

of the Cave Temple but may be of much later date.

The shrine of Baba Ramdin

Reshi and the tomb of his disciple Ruku-din-Reshi are also close by. Hugel

statues that the Bhumju caves occupy a very conspicuous place in the fables of

the timid Kashmiris, and are supposed to have originated from the following

causes, In the year Kali 2108 ( 993 B.C) Raja Nara succeeded his father,

Vibishana; during his reign certain Brahman espoused

Chandrasaha , the daughter of Susravas, a serpent-god, whose place was in a lake

near the Vitusta , and near a city built and inhabited by Nara. One day, as Raja

Nara beheld the beautiful daughter of the serpent on the shore of the

lake, moving gracefully through the calm waters, he was struck with

the deepest admiration, and endeavored vainly to inspire the same

sentiments he himself felt. At length he resolved to carry her off from husband,

but the plan failed, and the enraged Brahman called on her father to avenge the

insult. A storm was accordingly called up, and the earth open and swallowed up

the King and his whole Court. The sister of the serpent-god assisted him, and

hurled on the city huge stone from Bawan Mountain. The caverns of Bhumju are

said to be on the spot where these rocks were uptorn (Hugel, Growse)”.3

Notes and References

-

The

Temple Legacy of Kashmir: Account from Burried History by Sh. S.N. Pandit

published in Vitasta Annual Number, Volume XXXV (2001-2001).

-

Encyclopedia:

Kashmiri Pandit: Culture & Heritage by C.L. Kaul, published by Ansh

Publications, 2009.

-

The

Valley of Kashmir by Sir Walter Roper Lawrence.

-

Place Names in Kashmir by B.K.

Raina and S.L. Sadhu, published by Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Mumbai and Indira

Gandhi National Centre for Arts, New Delhi, 2000.

-

Ancient Monuments of Kashmir by

Ram Chand Kak, published by Aryan Books International, New Delhi, 2000.

-

Kalhan’s Rajatarangini - A

Chronicle of the Kings of Kashmir, Vol: II by Stein, Aurel, published by

Motilal Banarasi Dass, 1979.

Image Gallery: http://ikashmir.net/gallery/categories.php?cat_id=277

|